by Kristen Goodhue

Carrie Bow Cay, the Smithsonian’s tropical island field station in Belize. (Credit: Zachary Foltz/Smithsonian Marine Station)

Caribbean corals have been through a rough few decades. Between the 1970s and early 2000s, the region’s hard coral coverage dropped over 80%, largely fueled by climate change and harmful algal growth from overfishing and pollution. But on the island of Carrie Bow Cay in Belize, biologists discovered signs of a possible comeback.

Stony corals on the island’s outer rings—known as forereefs—more than doubled in just five years. A new study published this fall in the Nature journal Scientific Reports documents the recovery.

“Stony corals are your reef-building corals. Those are the ecosystem builders,” said Luis de Pablo, lead author of the study. “Those are what create the reef habitat, and those are the ones that we’re really concerned about.”

Carrie Bow Cay is part of the Mesoamerican Reef, the largest barrier reef in the western hemisphere. The Smithsonian has operated a field station on the island since 1972. It’s also part of the Smithsonian’s Marine Global Earth Observatory (MarineGEO), a network of over a dozen coastal sites sharing data all around the world. As part of their surveys, MarineGEO scientists had taken nearly a thousand underwater photos off the shore of Carrie Bow Cay Field Station from 2014 through 2019.

Luis de Pablo, former intern and lead author of the study, collects crayfish as part of his undergraduate thesis work. (Credit: Lucy Carlson)

De Pablo, now a senior at Amherst College, began the project as a 2019 summer intern with MarineGEO at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. His mentor, Jonathan Lefcheck, knew those photos contained a wealth of data about coral health. But analyzing hundreds of photos was a daunting enterprise.

“He could have sat there and scored all the images himself. Would he have finished in a summer? Maybe, maybe not,” Lefcheck said. “And so that’s when we started thinking about these machine-learning tools.”

They used a computer program called CoralNet, developed by Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute scientist David Kline and colleagues in 2011. De Pablo taught it to identify groups of organisms or terrain, like stony corals, soft corals, macroalgae or sand.

As it happened, de Pablo did not finish in a single summer. By the time his internship ended, they had just begun detecting some interesting trends. So he stayed on with the project remotely for the next two semesters, and again through the summer of 2020.

A photo quadrat from Tobacco Reef in Carrie Bow Cay, showing a mix of staghorn coral, soft corals and macroalgae. (Credit: Smithsonian MarineGEO)

They discovered on the outer forereefs, stony coral coverage doubled from 6% to 13% coverage. On more inner reefs, stony corals took a slight dip at first, but by 2019 bounced back to their original levels of around 12% coverage.

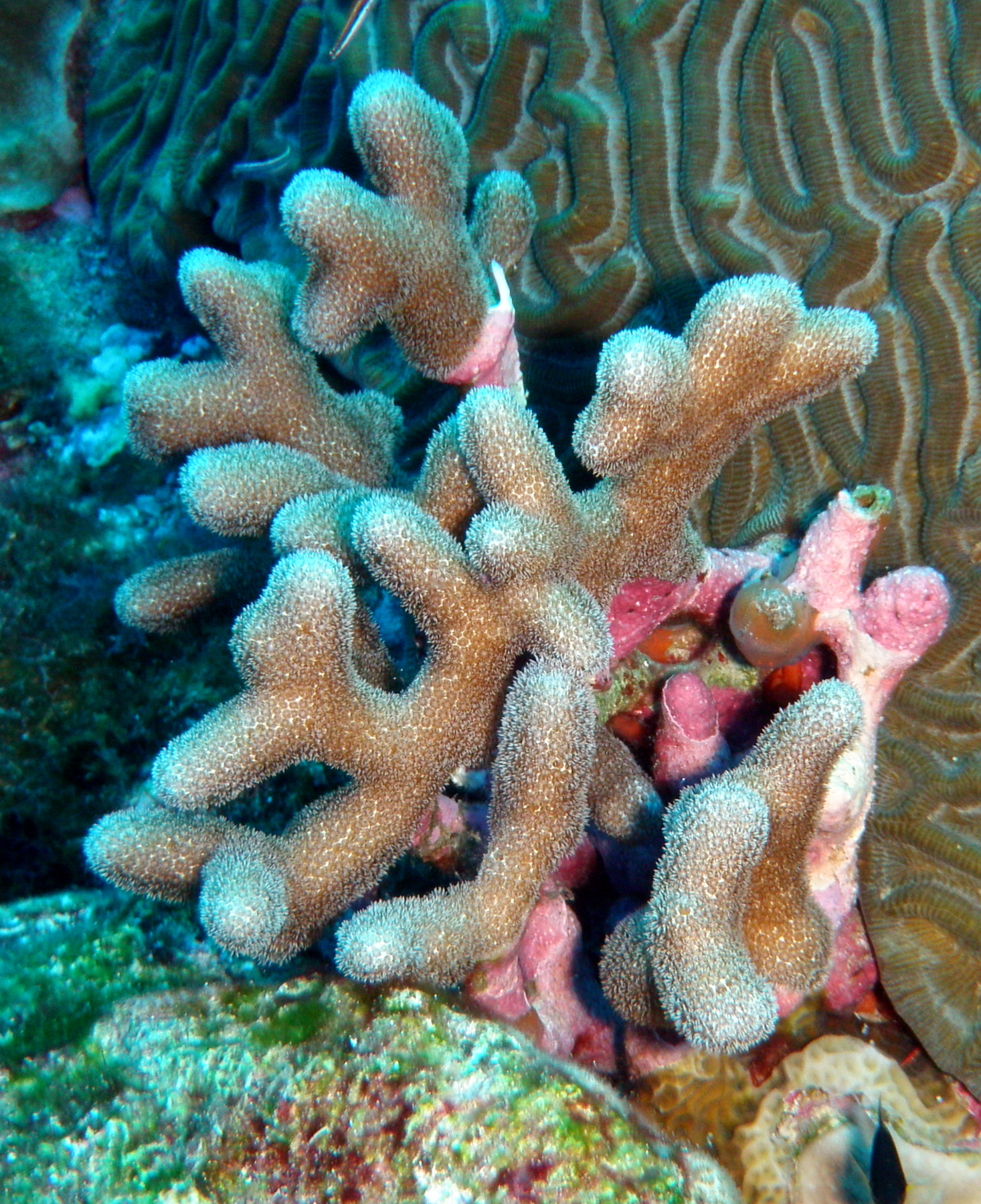

Clues to the comeback emerged when they took a closer look at the species involved. In 2019, other members of the team had done more in-depth species surveys of the reefs. They found “weedy” or fast-growing species leading the charge, like staghorn corals or finger-like Porites corals. Lefcheck speculates that the outer reefs, with cleaner water and more fish to graze off algae, provided an ideal environment for fast-growing corals to thrive.

Porites coral, one of the “weedy,” fast-growing corals that contributed to the recovery. (Credit: NOAA)

Marine protected areas could also be giving them a boost. Belize has created a number of marine protected areas, where fishing is limited or completely prohibited. Those efforts appearing to be paying off: A 2020 report card showed Belize had the highest reef health score of any country on the Mesoamerican Reef. Carrie Bow sits inside one of those marine reserves, and could be benefiting from the extra protections.

“I think it’s a very hopeful thing, that if we make the right protections and we enforce them properly, then ecosystems can recover,” de Pablo said.

Nevertheless, reefs throughout the Caribbean continue to face threats, most recently from the arrival of a new disease known as “stony coral tissue loss disease.” First seen in the Florida Keys, the disease is now racing across the region with catastrophic effects. Whether the recovering reefs at Carrie Bow will be able to withstand their own pandemic remains to be seen. But for now, the entire island can benefit from their recovery.

The Smithsonian Marine Station, the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, the Oregon Institute of Marine Biology and the Zukunft-Umwelt-Gesellschaft gGmbH International Climate Initiative also participated in this study. The full article is available at https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-96799-2.

Excelent and encouraging results in such a short time. Keep going !