Posted by Kristen Goodhue on March 24th, 2016

by Kristen Minogue

Melissa McCormick kneels over a cranefly orchid. (Yini Ma)

The secret is in the soil. In one of the oddest couples in the natural world, orchids need fungi to grow. But finding those fungi can be tricky, until a new study from the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) used DNA to find them in more places than anyone suspected.

There are 14 federally endangered or threatened orchids in the U.S. alone, and dozens more are endangered or threatened at the state level. Figuring out how to restore any single species is difficult, because there are so many different kinds.

“You’re talking about the largest plant family in the world,” said Melissa McCormick, lead author and SERC molecular ecologist. Orchids grow from islands off Antarctica to the Arctic Circle and just about everywhere in between. “They grow in darn near every environment on Earth.” But for all their diversity, the planet’s 26,000-plus known orchid species have one thing in common: None can germinate in the wild without a suitable fungus. Click to continue »

Posted in Publications, SERC Sites and Scenes | Comments Off on DNA Offers New Hope for Saving Orchids

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on February 14th, 2016

Enjoy these three groovy and very punny ecology-based Valentine’s Day Cards. To download and print full size cards, please select the pdf option. To save as images to share on the Web, please click the jpeg option.

Striped bass (Morone saxatilis) fry and copepods

Some fish like striped bass (Morone saxatilis) are born with a nutritive yolk sac. As striped bass develop, their yolk sacs shrink and their mouths develop. When fish are the stage where they are able to eat on their own they are called “fry.”

Download: Small Fry Valentines Card

PDF Format

JPEG Format

Click to continue »

Posted in Publications | 2 Responses »

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on February 11th, 2016

by Jan Payne Wilson, SERC Volunteer

Six-spotted fishing spider, Dolomedes triton. Credit: Derek Ramsey

My dad was uncomfortable around spiders. Today we’d probably say he had a phobia. To deal with it, he found a spider-like creature, the Daddy Long Legs, and learned how benign and beneficial it was. From then on, he could focus on a “good spider” rather than his fear. As a child, I was indoctrinated with the knowledge that a Daddy Long Legs 1) could not bite you and 2) performed good deeds by eating “bad” spiders and other biting, child-frightening insects. Furthermore, they needed our help because they had delicate legs that easily broke off, so we moved them out of dangerous areas and avoided stepping on them. When I was older my father revealed that Daddy Long Legs weren’t actually spiders. Unlike true spiders, they can’t make silk and have neither fangs nor venom. From my father I learned that understanding a creature often changes fear into appreciation and, sometimes, amazement.

On the docks of the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC), I use my dad’s strategy to help students who either fear spiders or believe the only good spider is a dead spider. With Daddy Long Legs it’s easy. But we also have large spiders we don’t see as frequently: fishing spiders. When you see your first fishing spider, it’s a hard sell to believe she’s got redeeming characteristics. Click to continue »

Posted in Ecology, Education, SERC Sites and Scenes | Comments Off on The Everyday Naturalist: Fishing Spiders

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on February 3rd, 2016

by Kristen Minogue

Tom Jordan beside a V-shaped weir that tracks nutrients in a SERC stream. (SERC)

For years, a team of scientists has been trying to solve a mysterious disappearance at a drainage ditch on the Choptank River Basin, on Maryland’s eastern shore. Every year roughly 32,000 pounds of human-generated nitrogen enters the ditch’s watershed, from fertilizers, air pollution and other sources. But less than a third of that nitrogen typically flows out of the stream.

Tom Jordan has seen it before. A nutrient ecologist at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC), Jordan has wrestled with the mystery of the missing nitrogen for more than twenty years.

“It feels like a sort of fatal attraction,” Jordan said. Two decades of trial and error and dead ends only fueled his determination to find answers. Now, according to a new January study, Jordan and his colleagues finally have some.

Click to continue »

Posted in Ecology, Land Use, Publications, Water Quality | 2 Responses »

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on January 22nd, 2016

Jellyfish, cownose ray and blue crab snowflakes

by Heather Soulen

Winter storm Jonas is knocking on our doorsteps here on the East Coast, threatening blizzard conditions in some areas. Many of us will be hunkering down waiting for the storm to pass. We thought we’d create some fun Chesapeake Bay inspired snowflake designs for you and your family to create during the storm. Simply download the pdfs, print them out and follow the instructions at the bottom.

There are four designs to choose from, the easiest being the cownose ray and the most difficult being the blue crab. We’ve provided a blank template for you to create your own Chesapeake Bay or nature inspired design. Since this requires the use of scissors, parents please assist small children.

We’d love to see your snowflakes – be sure to post pictures of your snowflakes on our Facebook page or on Twitter!

Click to continue »

Posted in Extreme Weather, Fisheries, Publications | 1 Response »

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on December 31st, 2015

by Kristen Minogue

It’s been another wild year at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. We sent a sailboat to the Arctic, pitted our orchids in a showdown against the Hope Diamond and discovered a couple new species. And somewhere along the way we celebrated the center’s 50th anniversary. Scroll below for the 2015 #YearInReview, a collection of the top 12 stories, journeys and biggest surprises of 2015.

Cownose Rays (SERC/Laura Patrick)

Exploring the Ocean

Totes Adorbs! Cownose Rays Take Internet

These marine heartthrobs have earned a top billing. Besides making a 900-mile migration every year, which SERC marine ecologists are tracking with acoustic tags, the kite-shaped rays (whose mouths are stretched so that they seem to be wearing a perpetual smile) also won a Twitter #CuteOff in September.

What Does Life in the Ocean Sound Like?

Postdoc Erica Staaterman listens to the ocean for a living. Often seen as a silent landscape broken only by whale or dolphin songs, Staaterman is helping uncover a wealth of noise from the ocean’s hidden creatures. She shared some of the recordings with us in this edited Q&A.

Cruising the Arctic’s Forgotten Fjords

Ocean acidification researcher Whitman Miller sent one of his CO2-monitoring devices on a 100-day journey to the Arctic. Its mission: Venture to some of Greenland’s never-before-seen fjords and discover how melting glaciers are changing the water. And do it all in a small, 42-foot sailboat. Click to continue »

Posted in Climate Change, Ecology, Fisheries, Invasive Species, SERC Sites and Scenes, Water Quality | Comments Off on Top 12 Highlights of 2015: Arctic Sailing, Cownose Rays and an Orchid Showdown

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on December 22nd, 2015

by Kristen Minogue

Ecologist and lead author Josh Caplan holds a Phragmites plant at the Global Change Research Marsh. Invasive Phragmites can grow up to 15 feet tall. (Thomas Mozdzer)

One of the Chesapeake’s least favorite invaders could end up being an unlikely savior. The invasive reed Phragmites australis, a plant that has exploded across Chesapeake wetlands in the last few decades, is also making those wetlands better at soaking up carbon, ecologists from the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) and Bryn Mawr College discovered in a new study.

The common reed, better known as Phragmites australis, grows in dense clusters up to 15 feet tall. North America has several native strains that have co-existed peacefully with many other native plants for at least 30,000 years. It is the invasive strain that arrived from Eurasia in the 1800s that has scientists and environmental managers worried. Eurasian Phragmites grows taller and denser than North American Phragmites, crowding out many smaller plants, and blocking access to light and nutrients. These changes in plant community have a ripple effect on animals that rely on wetlands for habitat.

“The fish communities, the insect communities, the soil and invertebrate communities, all these things change when Phragmites comes in,” says lead author Josh Caplan, a Bryn Mawr postdoc and visiting scientist at SERC. Often, those changes aren’t for the better. “Phragmites is doing a number to these ecosystems.” Click to continue »

Posted in Climate Change, Ecology, Invasive Species, Land Use, Publications, SERC Sites and Scenes | Comments Off on Phragmites vs. Climate Change: Invasive Reed Better at Taking Up Carbon

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on December 21st, 2015

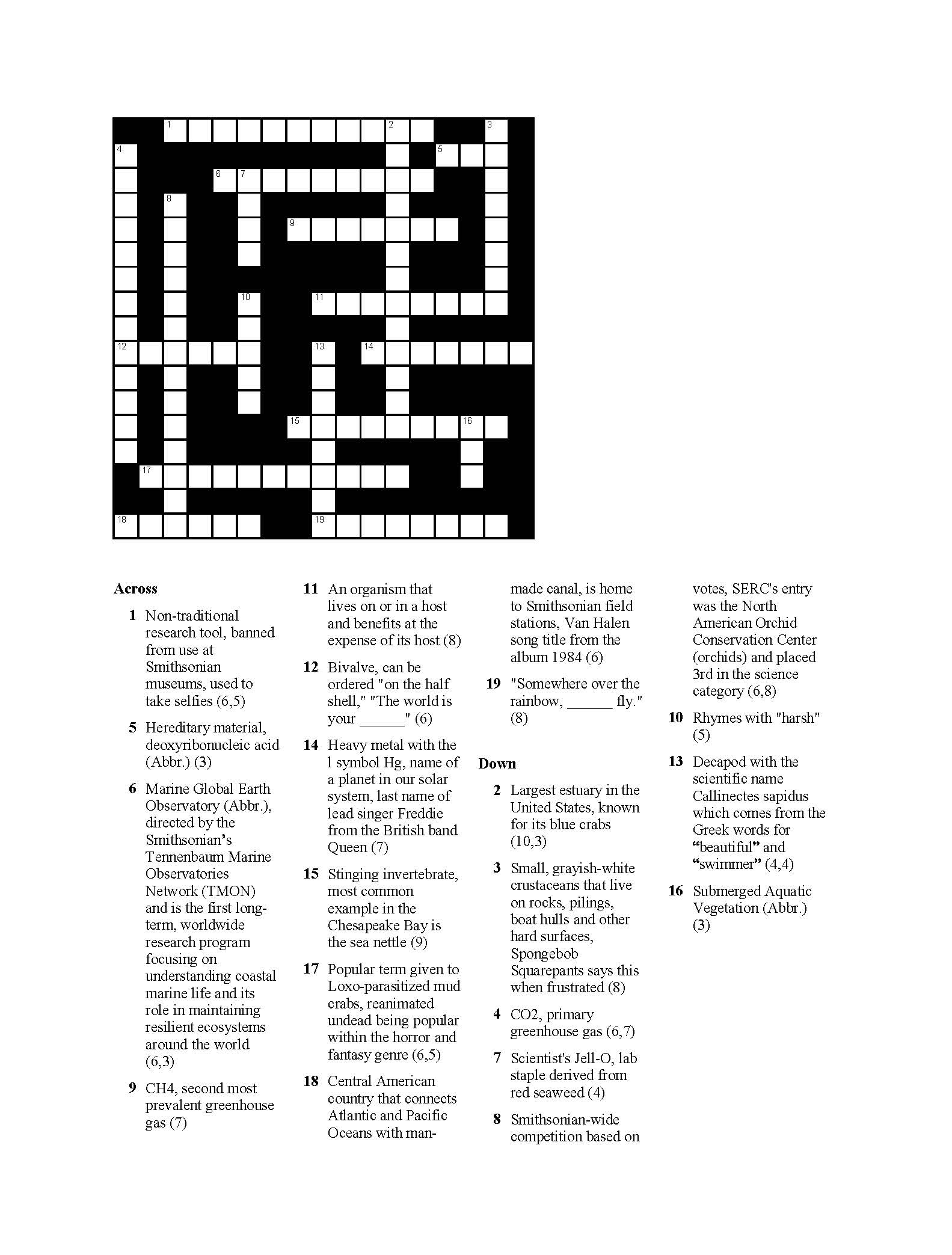

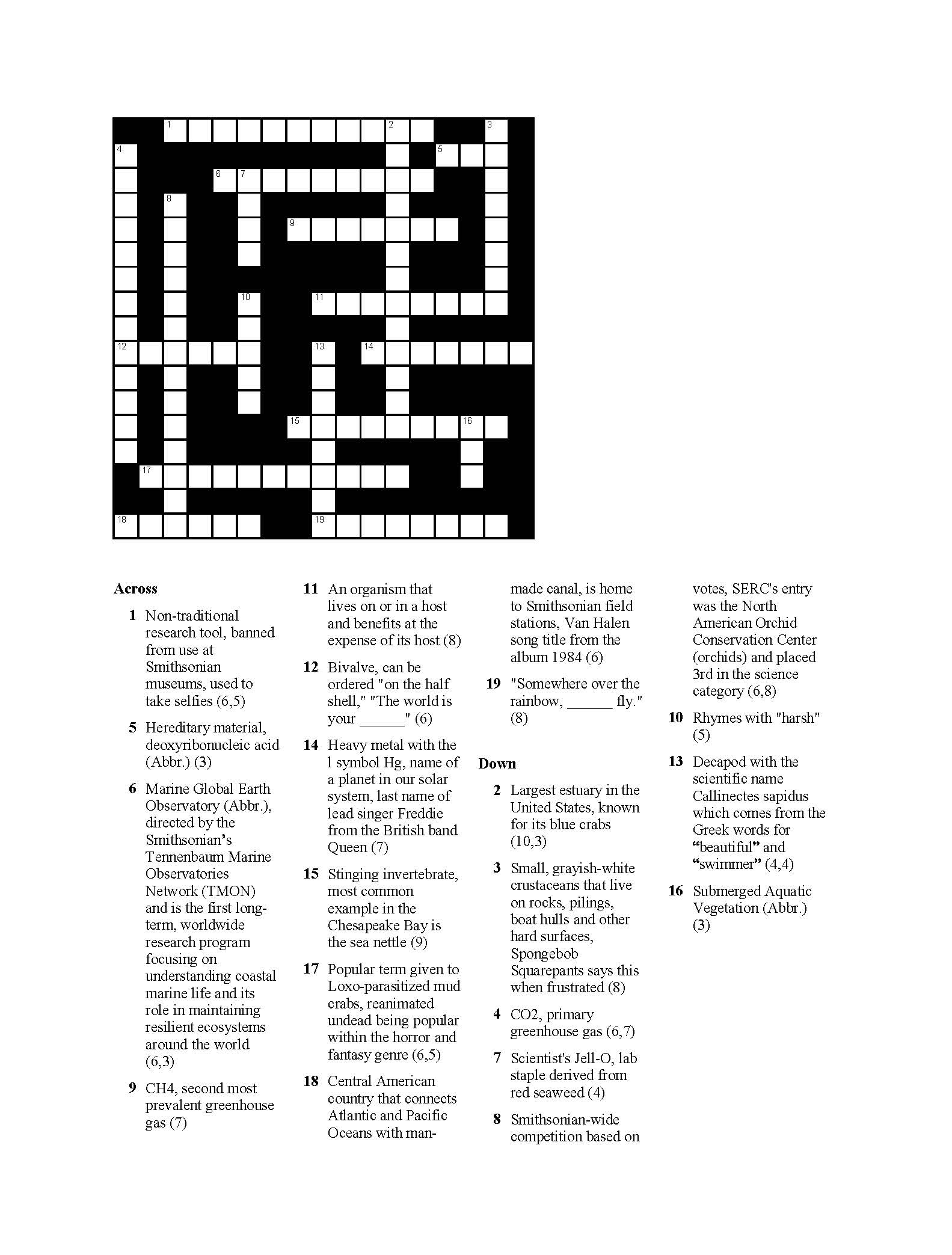

Enjoy our Smithsonian science-based crossword puzzle in celebration of Crossword Day. Words for this puzzle were derived from our blog posts in 2015. Stumped? Search our blog posts for additional clues or click the Reveal Letter button for help. Good luck and may the force be with you!

Online version: http://crossword.info/Soulenfish/Ecology_Flair_Final

Posted in Publications | Comments Off on A Crossword Puzzle with Ecology Flair

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on December 17th, 2015

Bivalves from Panama for Dermo disease study

by Heather Soulen

Last week Nature magazine published a news piece about how supplies of agar, a research staple in labs around the world, are dwindling. Agar is a gelatinous material from red seaweed of the genus Gelidium, and is referred to as ‘red gold’ by those within the industry. Insiders suggest that the tightening of seaweed supply is related to overharvesting, causing agar processing facilities to reduce production. Most of the world’s ‘red gold’ comes from Morocco. In the 2000s, the nation harvested 14,000 tons per year. Today, harvest limits are set at 6,000 tons per year, with only 1,200 tons available for foreign export outside the country. In typical supply and demand fashion, distributor prices are expected to skyrocket. As a result, things could get tough for scientists who use agar and agar-based materials in their research.

Agar is a scientist’s Jell-O. Just like grandma used to make Jell-O desserts with fruit artfully arranged on top or floating in suspended animation within a mold, scientists use agar the same way. Bacteria and fungi can be cultured on top of nutrient-enriched agar, tissues of organisms can be suspended within an agar-based medium and chunks of DNA can move through an agarose gel, a carbohydrate material that comes from agar. Agar and agar products are the Leathermans of the science world.

Click to continue »

Posted in Climate Change, Ecology, Fisheries, Invasive Species, Parasite Hunting, Publications | Comments Off on Restrictions in Seaweed Agar-vate Scientists

Tags: agar, agarose, bivalves, clams, Dermo, disease, DNA, ecology, endobacteria, fungi, fungus, gel, marsh, microbiome, nutrient pollution, Orchid, oysters, parasites, Perkinsus, Phragmites, science, seaweed, Spartina

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on November 25th, 2015

New report enables creation of carbon credits for restored wetlands

by Kristen Minogue

SERC’s Global Change Research Wetland (Credit: SERC)

How much is a wetland worth?

It’s a question that has plagued policymakers, scientists and other leaders looking to protect their communities and slow down the pace of climate change. For the first time, thanks to a new report released Tuesday, scientists have a method to calculate how much greenhouses gas emissions a restored wetland can offset that can be used anywhere in the world–which will allow the creation of carbon credits. Click to continue »

Posted in Climate Change, Ecology, Publications | Comments Off on The Blue Carbon Market Is Open