by Kristen Minogue

How exactly does one prepare for a 100-day voyage to the Arctic?

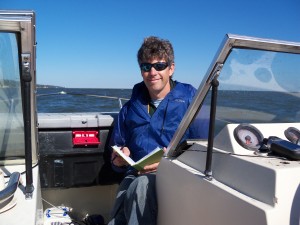

“Chaotically,” says Matt Rutherford, head of the nonprofit Ocean Research Project. He’s sitting in the cabin of the Ault, a 42-foot-long sailboat in Annapolis that will embark the next day on a research cruise to Greenland. Rutherford and his partner, Nicole Trenholm, will navigate unexplored fjords collecting data for the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) and NASA. The 8,000-mile round-trip journey will take them to some of the few uncharted spots left on the map. But first they have to finish packing.

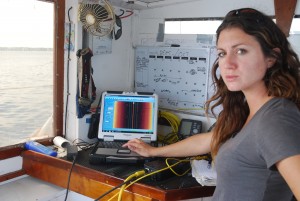

“You’re always paying attention to how much water you have, how much power you have, how much fuel you have,” says Trenholm, a marine scientist who joined Rutherford in 2013. “It’s kind of a game.”

To conserve water, they’re running the sinks and showers with saltwater. The cabinets in the Ault’s galley are stuffed with trail mix, spices, Swiss Miss cocoa and freeze-dried food.

There’s something else in the cabinets as well: a small orange box secured with bungee cords, with tubing running up to the mast. The box, and the three clear tubes lashed to the mast above it, is an instrument designed by SERC ecologist Whitman Miller, and it’s the main reason they’re going on this voyage at all.

Sailing for Science

The voyage to Greenland will not be Rutherford’s first to the Arctic. In 2012 he completed a 310-day journey circumnavigating North and South America alone.

“When I got back from that, I knew I was never going to stop sailing, so I wanted to do it in a way that was going to give back to the ocean,” he says. He launched the Ocean Research Project with Trenholm, who was then surveying the seafloor for NOAA. Their mission was simple: Sail the world’s waters collecting data for scientists, without the hefty price of larger research vessels that can cost between $20,000 and $25,000 a day. (For the Arctic voyage, Rutherford and Trenholm are operating at $250 per day.)

They started by mapping oysters in the Rappahannock, and surveying plastic pollution in the North Atlantic and across the Pacific. Last summer they listened for tagged fish for SERC marine biologist Matt Ogburn. From the beginning they wanted to return to the Arctic. But they ran up against two roadblocks: funding, and the skepticism of other scientists. Not everyone was convinced a two-person sailboat could handle sophisticated science around the poles. That changed when they met Smithsonian Environmental Research Center ecologist Whitman Miller.

Miller studies ocean acidification in waters off Maryland—though, personally, he prefers the term “ocean carbonization.”

“Really what’s affecting things is the CO2,” Miller explained. As oceans are forced to swallow more CO2 from the atmosphere, they become more acidic, bleaching corals and stifling shell growth in oysters and other bivalves. “If we didn’t have changes in carbon dioxide concentrations in the water, this issue of acidification would be much less important.”

Miller designed a device which continually measures the concentration of CO2 in the water. It’s the three-cylinder instrument strapped to the Ault’s mast, with the data box stashed in the galley. It’s not the world’s first device tracking CO2 in water, any more than the Ault is the first Arctic research vessel. But before Miller, similar instruments could costs tens of thousands of dollars. His creation costs mere hundreds, allowing scientists to collect precise data without bleeding them dry.

He had already stationed five in the Chesapeake, Florida and Panama for the Smithsonian’s MarineGEO network, and he envisioned collecting CO2 data from around the globe. When Rutherford and Trenholm offered the chance to make his invention mobile, he didn’t hesitate.

“To me it was a no-brainer,” he said. After Miller, they found two NASA projects also willing to bet a sailboat could step into the ring of Arctic research with the heavyweights.

Dangers of the Ice

The Greenland fjords enclose one of the rarest things on Earth: uncharted waters. Many have never been explored, so Rutherford and Trenholm will navigate rocks, currents and 20-foot tides with only their eyes and what Rutherford calls “sailor’s intuition.” There will be long, sleepless nights. On most ocean voyages, only one person needs to be on watch, but the treacherous Arctic demands two.

Three times the size of Texas, Greenland is the beating heart of climate change in the Northern Hemisphere. If the entire Greenland ice cap melted, it would create an estimated 24 feet of sea-level rise. But the island poses another threat. The freshwater from melting glaciers makes the oceans less salty—and less salty waters are more vulnerable to acidification. Saltier waters can absorb extra CO2 without changing their acidity (pH) as much. But in freshwater, CO2’s impact becomes far more drastic.

“If you add the same amount of CO2 to a fresher water or less buffered water, the change in pH is going to be much greater,’ Miller said.

All three feel they have something to prove on this journey. For Miller, the voyage is a double test: first, that his invention will work at sea for 100 days and, second, that it could one day be run by citizen scientists who, unlike Trenholm, have zero scientific training. For Rutherford and Trenholm, it’s about proving a sailboat—long reduced to a mere pleasure craft—can have a place in the world of science.

But once they lift anchor, their biggest enemy is time. Rutherford estimates they have a six-week window when the fjords will remain open.

“The Arctic, it ain’t waiting for us,” Rutherford says. “It’s going to open up, and when it does, either we’re going to be there or we’re not. And if we’re there, we can get our data. And if we’re not, then everything’s for nothing.”

Where are they now? Follow the Ault’s journey in real time on the Ocean Research Project webpage.

Watch: Whitman Miller explains the wild CO2 of the coast

http://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d4QAe4Dx3OM