by Marissa Sandoval

This is Part 2 of a series that explores the concerns of invasive species introduced by ballast water and the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center’s role in combating them. Part 1 offered an overview of ballast water and the threats it poses to coastal communities. Part 2 dives into SERC scientists monitoring invasions and researching solutions.

Whenever a truck brings fresh fruits and veggies into the U.S., an inspector checks them for disease or insect pests. But what about imports that come from the ocean? Global shipping has long caused concern over invasive species spread. If introduced species on land are a headache for environmental managers, then successful marine invaders are chronic migraines. They’re terribly difficult to locate, catch and eliminate out in the open ocean and even in large bays. And even when teams spend years of hard work, nature—even non-native species—somehow finds a way.

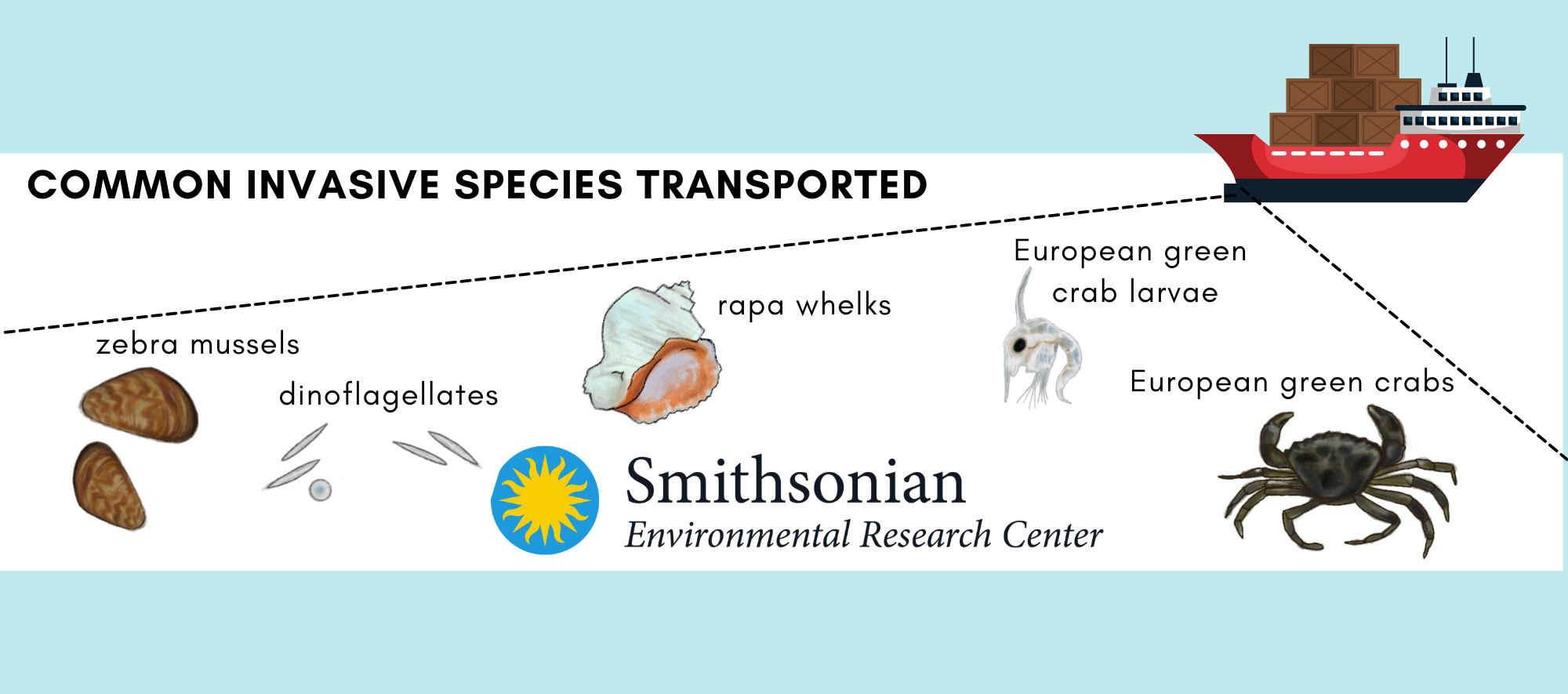

To be fair, the vast majority of introduced marine organisms have negligible impacts. Those comparatively harmless species outnumber by far the aggressive ones we hear about in the news. However, the lucky few invertebrates that do get a bad reputation—like the ones in the infographic below—have usually earned it. These species often hurt native species and the surrounding environment. Worse, they can spread like wildfire in the bay.

(Infographic by Sofia Baah and Marissa Sandoval)

(Infographic by Sofia Baah and Marissa Sandoval)

Taking Stock Of What’s In The Water

Biologist Kim Holzer lowers a nylon mesh net into a ship’s ballast tank, to see how many microorganisms are present. (Credit: Kim Holzer)

In the highly invaded San Francisco Bay, researchers from the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) have continuously monitored invasive species communities for over two decades. Each year, SERC scientists deploy underwater panels in marinas for invertebrates to colonize for three months. Another SERC team uses tall, cone-shaped nets to collect phytoplankton and zooplankton at different depths in the bay. After pulling up the panels and nets, researchers detect any new threats and record the species present and their relative abundance. Both teams then track how diversity changed over time and identify patterns crucial to management.

For example, California’s recent extreme wet and dry periods can trigger drastic species shifts. The decade began with a wet winter in 2011, followed in short order by a historically severe drought that lasted from 2013 to 2016, only to be ended by the wettest winter on record in early 2017. It turns out that wet years bring in enough freshwater to kill off salt-loving invertebrates. While that may sound like a bad thing, lead SERC-West scientist Andy Chang now views these years as opportunities. Wet years offer a window for managers to take action, to ensure that natives come back instead of their competitors.

“A really good time to increase management efforts could be following a major wet winter,” said Chang, “which can serve as a natural eradication of sorts, knocking back populations of invaders in some parts of the Bay long enough for restoration efforts to help native species get a better foothold.”

Stopping New Invaders In Their Tracks

Federal management began with the Invasive Species Act of 1996. Part of the new law called for a partnership between SERC and the U.S. Coast Guard, to oversee how ships manage the ballast water in their hulls for possible invaders. So began their joint program: the National Ballast Information Clearinghouse.

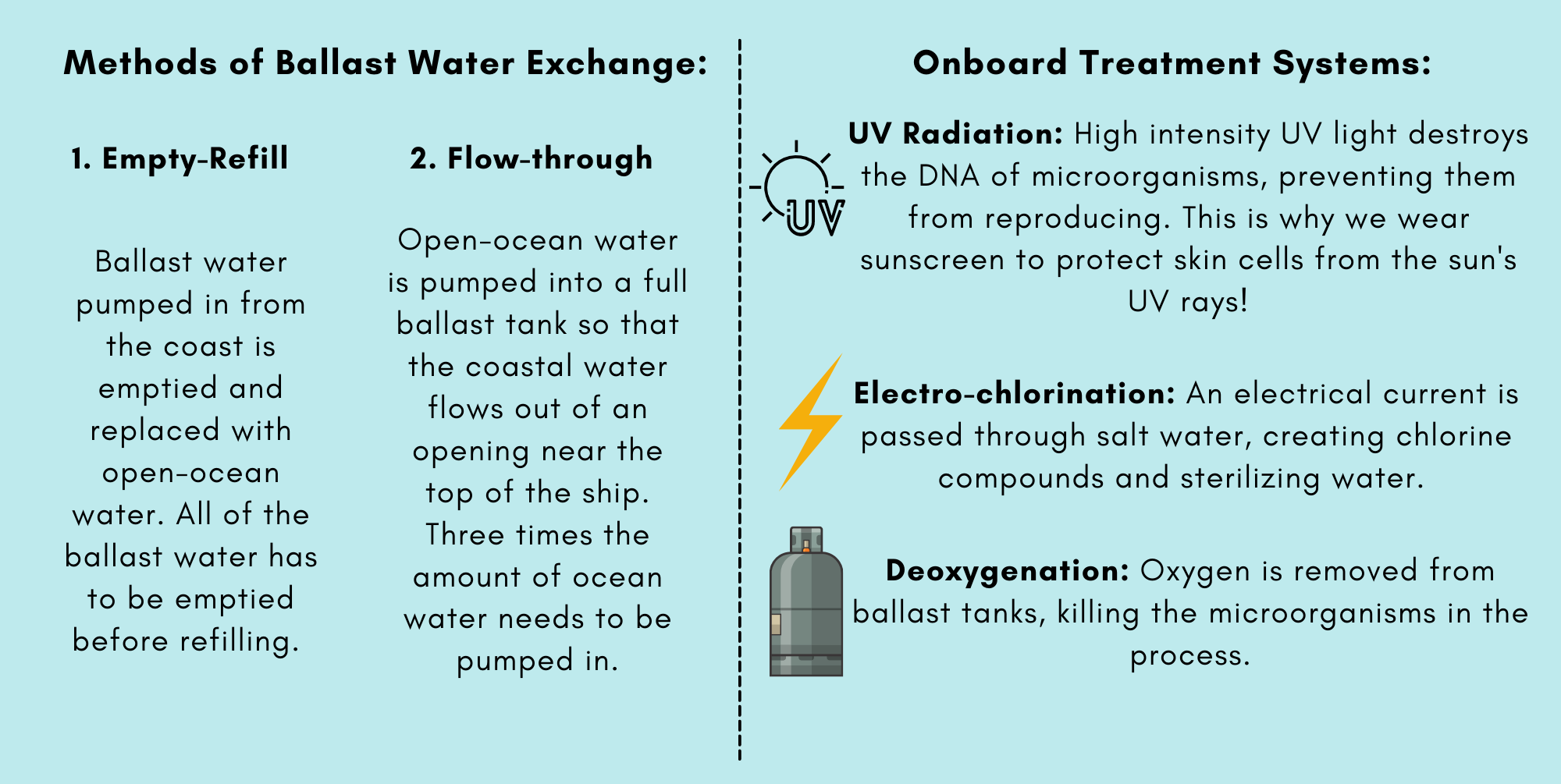

Commercial ships entering U.S. waters must report the origin and amount, if any, of ballast water discharged off the U.S. coast. They also must report how they treated it for potential invaders. At this time, the U.S. Coast Guard permits three practices: empty/refill exchange, flow-through, and on-board water treatment systems. Of the three, on-board treatment systems are considered the biosecurity gold standard.

SERC biologist Monaca Noble onboard the Lily Fortune, taking samples from the vessel’s ballast tank. (Credit: Kate Murphy/SERC)

(Infographic by Sofia Baah and Marissa Sandoval)

Just as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration limits how many insects or insect fragments are allowed in everyday foods we eat, the U.S. Coast Guard holds a limit for how many microorganisms can be present in a milliliter of water. Researchers like SERC’s Monaca Noble examine the samples to ensure shipping crews uphold the standards.

While empty/refill and flow-exchanges try to flush out hitchhiking organisms picked up from their source, onboard ballast water treatment aims to kill off potential invaders, almost like a surface disinfectant. SERC scientists continue to work with the Coast Guard to test the effectiveness of treatments like UV radiation, electrochlorination and deoxygenation. Those, among other systems tested by international agencies, seem to do the trick.

“This is all self reporting. You do have to have faith in the vessels,” says Clinton Arriola, a SERC research technician with the National Ballast Information Clearinghouse. “Ships tell us they sourced this water and tell us they discharged that water.”

What Makes A Harmful Invasion?

For ubiquitous invasive species or ones recently introduced to foreign areas, SERC scientists also want to know how exactly they got there and which areas might be vulnerable to introduction. With reports from the clearinghouse, scientists can map commercial shipping routes, see how many ships use those networks, and develop models that predict how organisms will spread.

Things like reproduction, food availability, temperature and salinity can all shape how well an invasive species can spread. Catherine Bubser, an intern with the Marine Invasions Lab, and her mentor Sarah Donelan are investigating the effects of temperature and food availability on acorn barnacles. Bubser’s findings can help researchers pinpoint target sites where the organisms may already have a foothold or may pop up in the future.

“Researchers doing damage control can aim their efforts on areas that match these temperatures,” Bubser said. “Where they can have more of an impact, that’s where they should be focusing their effort.”

That’s the ultimate goal: controlling established invaders while preventing new ones. Commercial shipping won’t be slowing any time soon. But maritime voyagers have been working with SERC to implement best practices when it comes to ballast water. And while that’s happening, come shell or high water, SERC scientists remain busy identifying invertebrates, photographing panels, counting microorganisms and working together to understand the patterns and processes behind invasions.

More in this series:

Out of the Ballast Tank & Into the Waters, Part 1: Hidden Hitchhikers Take a Transoceanic Trip