by Marissa Sandoval

This is the final article in a 3-part series about ballast water. Part 1 provided a brief history of ballast water and its accompanying invasive species threats. Part 2 illustrated how scientists from the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) are researching technology to prevent invasions and keeping an eye on current ones. This article shows how SERC scientists are working to predict vulnerable spots for ballast water invasion, using shipping networks and commercial trade information.

They say you can never step into the same river twice, since the water’s always running. The same could be said about waters on the shore. Not only do currents sweep the waves to and fro, but new seawater is also constantly being introduced from the ballast tanks of globetrotting ships.

It’s estimated that foreign ships discharge over 180 million metric tons of ballast water off U.S. coasts each year, according to the National Ballast Information Clearinghouse (NBIC). In each ton comes a chance for aquatic critters from foreign ports to invade new shores.

Compared to other vectors of invasive species introduction, like produce imports or the pet trade, ballast water stands out for the diversity of organisms it can bring in.

“When you take on ballast water in one place, you’re sucking up a huge sample of that community,” said Mark Minton, a quantitative ecologist with the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC). “You’re moving communities. Oftentimes this is from places where we don’t even really know what species are there.”

How do we get to a point where we can anticipate or be prepared for future invasions?

In a new study published this summer, SERC scientists took a first step. They predicted the amount of ballast water discharge in the San Francisco Bay Area by looking at trade goods. It turns out that if you take the top 11 commodities transported by tankers or bulk carriers—things like coal, oil, iron or recyclables—the vessels carrying those account for 92% of the total ballast water discharge off the coast of the San Francisco Bay Area!

This discovery shows how scientists can use trade data to estimate how much ballast water gets discharged in places where ballast records aren’t currently available.

How Trade Shapes Ballast Water

But what happens when the dynamics change? How does that impact the threat of invasion?

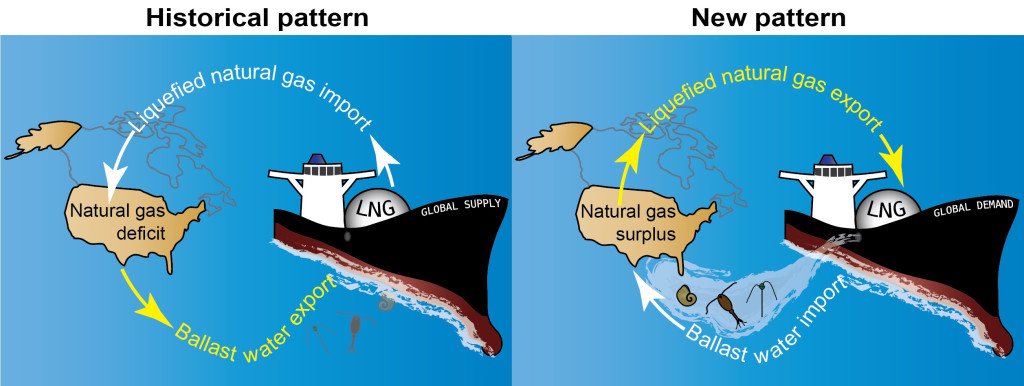

Consider what happened in 2015, when the U.S. transitioned from being a net importer of liquified natural gas to a net exporter. On the return voyage from foreign countries, after offloading their natural gas cargo, U.S. ships would have to bring ballast water back to the States. SERC researchers estimate that by 2040, there will have been a 90-fold increase in the volume of ballast water from the liquified natural gas trade that’s discharged off the U.S. coast. That’s around 42 billion liters, or roughly enough water to fill 16,800 Olympic-sized swimming pools!

Read More: Natural Gas Trade Opens Door For Invasive Species

Or consider the flipside. In 2018, China stopped buying recycling from the U.S. That decision sent shockwaves through many industries, including shipping and invasive species management. (Remember, recyclables had once been one of the top 11 commodities coming in and out of the San Francisco Bay Area.) Before, ships from China had been discharging water off the West Coast prior to loading up on our recyclables. But that came to an abrupt stop when we were no longer able to export recyclables.

Minton likes to think of the process like a faucet being turned on and off.

“When China stops buying our recycling, then the faucet gets immediately turned off,” he said. Though species introduction largely depends on two factors—how much water a vessel discharges and how frequently discharges happen—whether an invasion is successful ultimately boils down to odds. “They can be successful anytime, since this is a random process … Any time the faucet’s on, there’s an opportunity there.”

Getting Ahead of the Flow

Compared to other methods of spreading invaders, commercial shipping stands out for its ability to transfer species globally. The majority of goods get exchanged via maritime trade. By understanding patterns in international trade and vessel designs, scientists are hoping to predict—and more importantly, prepare for—future invasions.

In the meantime, SERC scientists are keeping an eye on the “faucet.” On the West Coast, researchers within the Marine Invasions Lab conduct regular suveys of the San Francisco Bay to check for non-native species. In Maryland, teams process shipping and ballast water data in collaboration with the U.S. Coast Guard as part of the National Ballast Information Clearinghouse.

Some situations call for more than just monitoring–“putting one’s finger in the dike,” so to speak. In those times, SERC scientists work closely with regulators to ensure that science helps inform new biosecurity measures. Researchers test on-board ballast water treatment technologies and readily share information about potentially harmful situations with the public, like the introduction of dangerous microorganisms.

In the past, people could only take action on invasive species after the fact, when the invaders had already gained a solid foothold. But SERC has been working to change that. The wide range of research in the Marine Invasions Lab covers all of the bases when it comes to invasive species: sampling ports, tracking shipping trends and advising policy. These scientists devote their careers to ensuring that ecosystems and coastal residents, marine and human alike, stay protected.

Dive Deeper:

Out of the Ballast Tank & Into the Waters, Part 1: Hidden Hitchhikers Take a Transoceanic Trip

Out of the Ballast Tank & Into the Waters, Part 2: How to Wrangle Invaders from Every Angle