The Northern Snakehead recently crossed into the Rhode River, marking its first appearance in this part of the Bay. Previously scientists thought the Bay's high salinity would hold them in the Potomac, but influxes of freshwater may have smoothed their way.

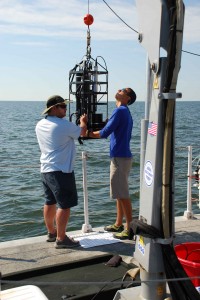

On the afternoon of Thursday, July 14th, a team of researchers and interns in SERC’s marine invasions lab went out on a routine seining survey in the Rhode River and returned with a troubling catch: a Northern Snakehead fish.

The Northern Snakehead (Channa argus) is a top-level predator that can consume fish and animals up to a third of its body size. It also has the ability to breathe out of water for up to four days if kept moist, using air chambers above its gills that can act as a primitive lung. (But reports of it walking on land are myths. They can at best wriggle short distances, and only juvenile fish have that ability.) More disturbing, at least to ecologists, is their ability to seriously disrupt the food chain wherever they establish themselves.

Native to China, the Northern Snakehead first appeared in Maryland in 2002, in a Crofton pond about 20 miles east of D.C. Regulators moved quickly to eradicate them, but two years later, they established themselves in the Potomac River. Since snakeheads thrive in freshwater (they typically cannot tolerate salinities higher than 15 parts per thousand), it was thought they would be unable to expand beyond the Potomac. But ecologists suspect an influx of freshwater into Chesapeake Bay could have paved the way for them to leave the Potomac and invade other tributaries, such as the Rhode River.

Important note: It is illegal to own or move a Northern Snakehead in the state of Maryland. If you do catch one, the Department of Natural Resources requests that you promptly dispatch it (freezing recommended) and contact the Maryland or Virginia DNR. Though some also suggest cooking it for dinner.

-by Kristen Minogue

See also: Narratives from two interns on the sampling team