Water Quality

...now browsing by category

Monday, August 8th, 2016

SERC intern Lauren Mosesso takes a water quality reading (Photo: Emily Li/SERC)

by Emily Li

One year ago, a team of scientists at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center set out to restore a stream running through its campus in Edgewater, Md. No one ever said it would be simple.

At first glance, the restoration of Muddy Creek seems to be a closed case. Before the project began, the creek’s severely eroded banks were disconnected from its floodplains, turning the stream into a raging river during storms that stripped nutrients from the system and dumped them in the Chesapeake Bay. Now, after a facelift in January, the creek is nearly unrecognizable. Its gentle banks cradle the wide, slow-moving stream littered with leaves, ferns, and an abundance of other plant life. Choruses of croaks fill the air, accompanied by the hum of insects, bird chatter, and the occasional splash of frogs retreating into the cloudy water.

But another layer of mystery is clouding the waters. A mat of red Leptothrix bacteria coats some sections of the site, leading SERC senior scientist Dr. Thomas Jordan and his colleagues to ask a host of new questions. Are the bacteria harmful to the ecosystem, or an important part of the food web? Are they a short-term phenomenon or a permanent fixture to the stream? Exactly how much area do they cover? One SERC intern is hoping to find out.

Click to continue »

Posted in Ecology, From the Field, Interns, Interviews, Land Use, SERC Sites and Scenes, Water Quality | 1 Response »

Thursday, August 4th, 2016

SERC intern Michelle Hauer sets up her soundscape ecology tank experiment (Photo: Emily Li/SERC)

by Emily Li

In high school, Smithsonian Environmental Research Center intern Michelle Hauer fell in love with sound. She discovered the cello, which she insisted on bringing to her internship this summer despite having limited space and housing. But her affair with sound didn’t stop there, even as she was exploring her interest in science. While still in high school, she wrote a paper on the effects of naval sonar on marine mammals. Then, while attending DePaul University, Hauer came across the relatively new field of soundscape ecology through a Chicago-based organization called Chicago Wildsounds—and she hasn’t looked back. Now, as a summer intern in SERC’s Fish and Invertebrate Ecology Lab, Hauer is studying the darker side of sound by researching how noise pollution can affect marine wildlife in the Chesapeake Bay and beyond.

Click to continue »

Posted in Ecology, Fisheries, Interns, Interviews, SERC Sites and Scenes, Water Quality | Comments Off on Making Noise About Marine Sound Pollution

Monday, August 1st, 2016

SERC intern Jasmin Graham cleans her equipment of marine organisms (Photo: Emily Li/SERC)

by Emily Li

Watching educational programs like Animal Planet or That’s My Baby—a series that documents pregnant animals—might evoke memories of flickering classroom projectors for most. But for Jasmin Graham, an intern with the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC), these shows were her childhood. Her love for marine science and wildlife followed her through high school science fairs and university research on shark genetics at the College of Charleston. Now, at an internship with SERC’s Ocean Acidification Lab, she studies acidification not in the open ocean, but in a far more dramatic arena, where the marine celebrities she grew up with may be at risk.

Click to continue »

Posted in Climate Change, Ecology, Extreme Weather, Fisheries, From the Field, Interns, Interviews, SERC Sites and Scenes, Water Quality | 1 Response »

Tuesday, May 10th, 2016

by Kristen Minogue

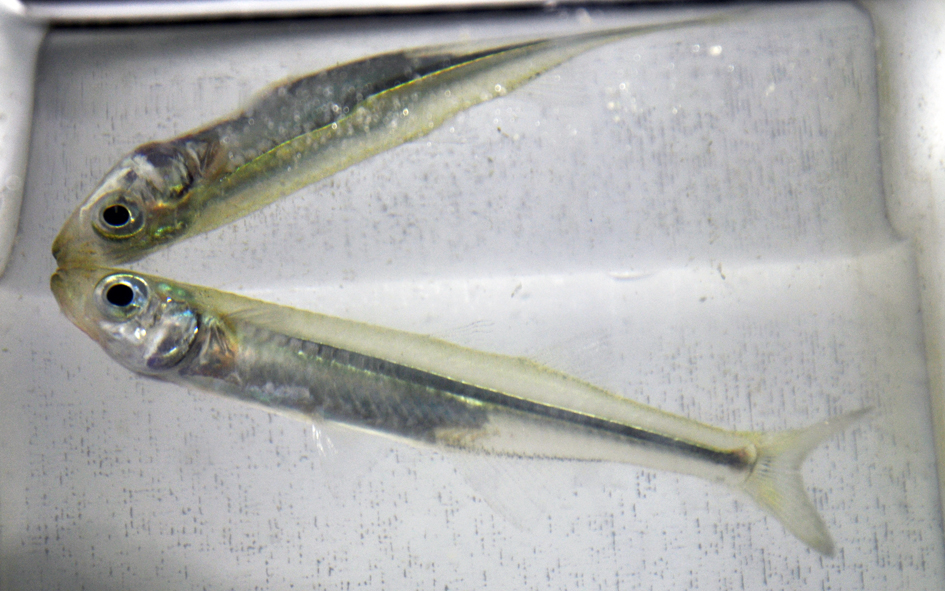

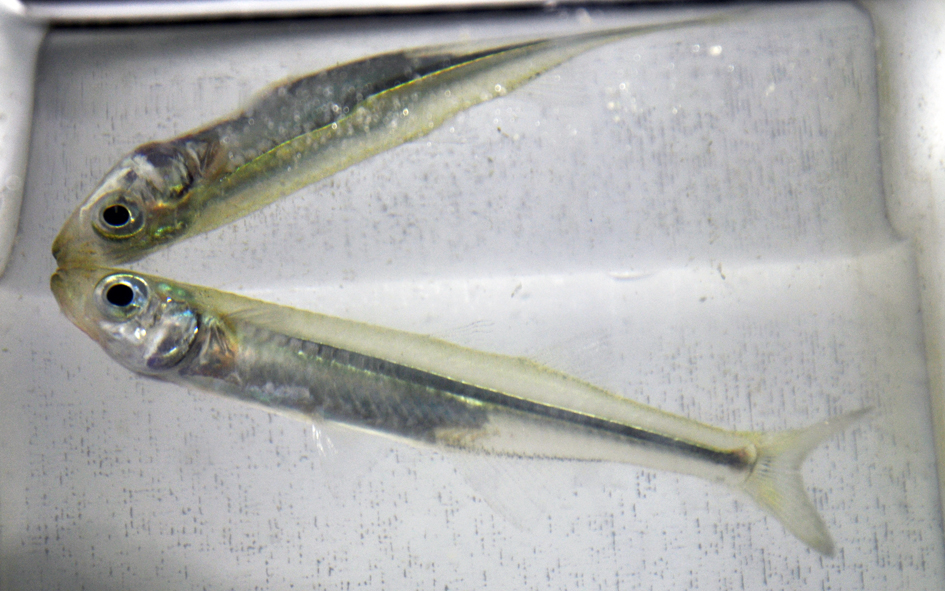

Inland silverside (Menidia beryllina) reflected in aquarium. When threatened with low oxygen, fish often swim to the surface, where oxygen is more abundant but predators can more easily spot them. (SERC)

Severe oxygen drops in the water can leave trails of fish kills in their wakes, but scientists thought adult fish would be more resilient to the second major threat in coastal waters: acidification. A new study published Tuesday from the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) shows that is not entirely true—where fish are concerned, acidification can make low oxygen even more deadly.

Click to continue »

Posted in Climate Change, Ecology, Fisheries, Publications, Water Quality | Comments Off on Acidification and Low Oxygen Put Fish in Double Jeopardy

Wednesday, February 3rd, 2016

by Kristen Minogue

Tom Jordan beside a V-shaped weir that tracks nutrients in a SERC stream. (SERC)

For years, a team of scientists has been trying to solve a mysterious disappearance at a drainage ditch on the Choptank River Basin, on Maryland’s eastern shore. Every year roughly 32,000 pounds of human-generated nitrogen enters the ditch’s watershed, from fertilizers, air pollution and other sources. But less than a third of that nitrogen typically flows out of the stream.

Tom Jordan has seen it before. A nutrient ecologist at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC), Jordan has wrestled with the mystery of the missing nitrogen for more than twenty years.

“It feels like a sort of fatal attraction,” Jordan said. Two decades of trial and error and dead ends only fueled his determination to find answers. Now, according to a new January study, Jordan and his colleagues finally have some.

Click to continue »

Posted in Ecology, Land Use, Publications, Water Quality | 2 Responses »

Thursday, December 31st, 2015

by Kristen Minogue

It’s been another wild year at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. We sent a sailboat to the Arctic, pitted our orchids in a showdown against the Hope Diamond and discovered a couple new species. And somewhere along the way we celebrated the center’s 50th anniversary. Scroll below for the 2015 #YearInReview, a collection of the top 12 stories, journeys and biggest surprises of 2015.

Cownose Rays (SERC/Laura Patrick)

Exploring the Ocean

Totes Adorbs! Cownose Rays Take Internet

These marine heartthrobs have earned a top billing. Besides making a 900-mile migration every year, which SERC marine ecologists are tracking with acoustic tags, the kite-shaped rays (whose mouths are stretched so that they seem to be wearing a perpetual smile) also won a Twitter #CuteOff in September.

What Does Life in the Ocean Sound Like?

Postdoc Erica Staaterman listens to the ocean for a living. Often seen as a silent landscape broken only by whale or dolphin songs, Staaterman is helping uncover a wealth of noise from the ocean’s hidden creatures. She shared some of the recordings with us in this edited Q&A.

Cruising the Arctic’s Forgotten Fjords

Ocean acidification researcher Whitman Miller sent one of his CO2-monitoring devices on a 100-day journey to the Arctic. Its mission: Venture to some of Greenland’s never-before-seen fjords and discover how melting glaciers are changing the water. And do it all in a small, 42-foot sailboat. Click to continue »

Posted in Climate Change, Ecology, Fisheries, Invasive Species, SERC Sites and Scenes, Water Quality | Comments Off on Top 12 Highlights of 2015: Arctic Sailing, Cownose Rays and an Orchid Showdown

Wednesday, February 11th, 2015

by Kristen Minogue

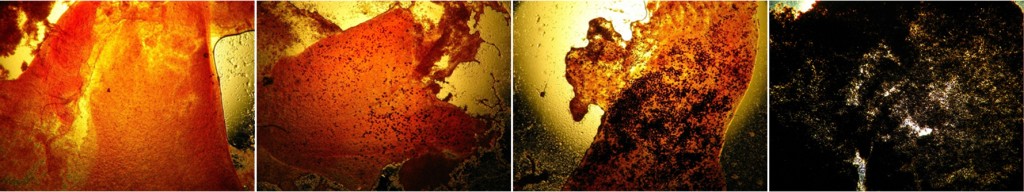

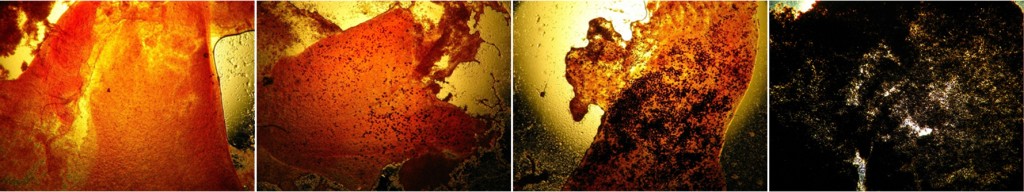

Slides of oysters suffering different Dermo intensities as the parasite multiplies, from healthy (left) to severely infected (right). (SERC Marine Ecology Lab)

In shallow waters around the world, where nutrient pollution runs high, oxygen levels can plummet to nearly zero at night. Oysters living in these zones are far more likely to pick up the lethal Dermo disease, a team of scientists from the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center discovered in a new study published Wednesday.

Oxygen loss in the shallows is a global phenomenon, but it is not nearly as well known as the dead zones of the deep. Unlike deep-water dead zones, which can persist for months, oxygen in shallow waters swings in day-night cycles, called diel-cycling hypoxia. In nature it works like this: When algae photosynthesize during the day, they release oxygen into the water. But at night, when photosynthesis stops, plants and animals continue to respire and take oxygen from the water, causing dissolved oxygen to drop. Nutrient pollution, because it fuels massive algal blooms, can make the cycle even more drastic. The resulting lack of oxygen can cripple the oysters’ ability to fight off the parasite Perkinsus marinus that causes Dermo and slowly takes over their bodies.

Click to continue »

Posted in Fisheries, Publications, Water Quality | 2 Responses »

Tuesday, September 30th, 2014

Jellyfish Chrysaora quinquecirrha (Lori Davias)

by Kristen Minogue

Every summer, the food web in Chesapeake Bay gets jostled around as two plankton-eating predators jockey for power: comb jellies and jellyfish. Most smaller species don’t have a stake in the battle—both predators eat zooplankton and fish eggs, after all. But for young oyster larvae, the victor could make the difference between being protected civilians or collateral damage.

Click to continue »

Posted in Ecology, Fisheries, Publications, Water Quality | Comments Off on Oysters and the Chesapeake’s Jellyfish Wars

Thursday, August 21st, 2014

By Sarah Hansen

Tony Thomas (left), education program coordinator at the Anacostia Community Museum, supervises while students Donovan Eason (center) and DaWayne Walker run a chemical test on a water sample.

“Is the net like a Spongebob jellyfish net?” student Cristal Sandoval asked. Alison Cawood, citizen science coordinator at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC), used another analogy to explain: “It’s like a bowl with holes in it for pasta.” Light bulbs came on around the room and a knowing, “Oh,” escaped the lips of at least a dozen students.

Click to continue »

Posted in Ecology, Programs, SERC Sites and Scenes, Water Quality | 2 Responses »

Tags: citizen science

Thursday, August 21st, 2014

by Melissa Pastore, biology graduate student at Villanova University

Melissa Pastore in a marsh near Delaware Bay.

(Lori Sutter)

What if we could create a giant sponge capable of soaking up nitrogen pollution? It turns out that the Chesapeake Bay, which has experienced a rapid increase in nitrogen pollution from municipal and agricultural sources over the last few decades, already contains a natural version of this sponge: marshes fringing the Bay. But global change—and the nitrogen pollution itself—could change how this natural sponge operates.

Click to continue »

Posted in Climate Change, Ecology, From the Field, Land Use, SERC Sites and Scenes, Water Quality | Comments Off on Marshes: Pollution Sponges of the Future