by Joe Dawson, science writing intern

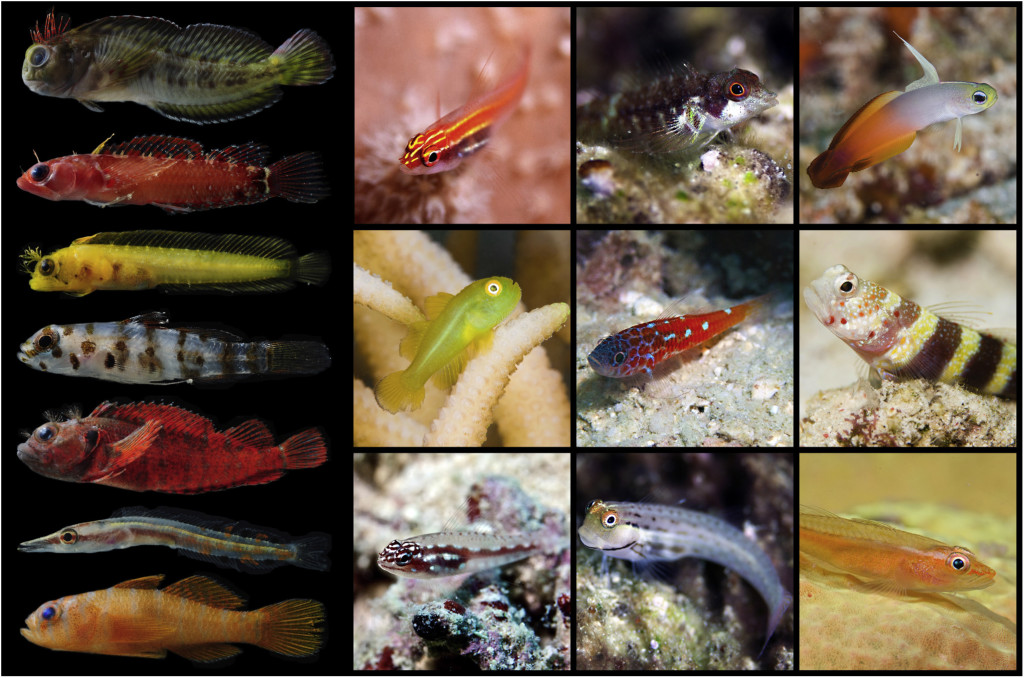

A sample of the diversity present within the cryptobenthic reef fishes. Figure from Goatley and Brandl 2017.

Go snorkeling on a coral reef, and you’ll have a hard time not being impressed by the abundance and variety of the fish there. But the fish most divers see make up less than half of the number (and less than half the species) of fish on the reef. Cryptobenthic reef fishes comprise the other half. These fish are small, usually less than 2 inches in length, and hide in coral habitats, either by appearance or by their behavior. Even scientists have been slow to start searching for them, but cryptobenthics are turning up in about every reef habitat where scientists have bothered to look! In the June 5 issue of Current Biology, SERC Scientist Simon Brandl and colleague Christopher Goatley of the University of New England published a quick guide to cryptobenthic reef fishes. Brandl thinks that these little fishes deserve more recognition, and we agree! Therefore, we’re happy to present these honorees with the following awards.

Coolest Camo

Runners Up: Frogfishes (Family Antennariidae), Scorpionfishes (Family Scorpaenidae)

The painted frogfish, Antennarius pictus (Credit: John E. Randall/Hawaii Biological Survey, used under CC BY-NC 3.0)

Weird and tricky, frogfishes have plump, short bodies. They’re often covered in spines or even hair-like appendages and prefer to stay still, waiting and blending in, for prey to swim close enough that they can gulp them. The deep-sea dwelling anglerfish is one famous member of this group.

Scorpionfish are also sit-and-wait predators, using their feathery scales or skin flaps to look like rocks or coral, then pouncing on nearby prey. The most renowned member of this group is the lionfish. Click to continue »