By Philip Kiefer

Alaska has a near-pristine marine ecosystem: There are fewer invasive species in its waters than almost any other state in the U.S. But that could be changing. With help from local volunteers, biologists at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) and Temple University have reported a new invasive species in the Ketchikan region, the invertebrate filter-feeder Bugula neritina, and documented the continuing spread of three other non-native species.

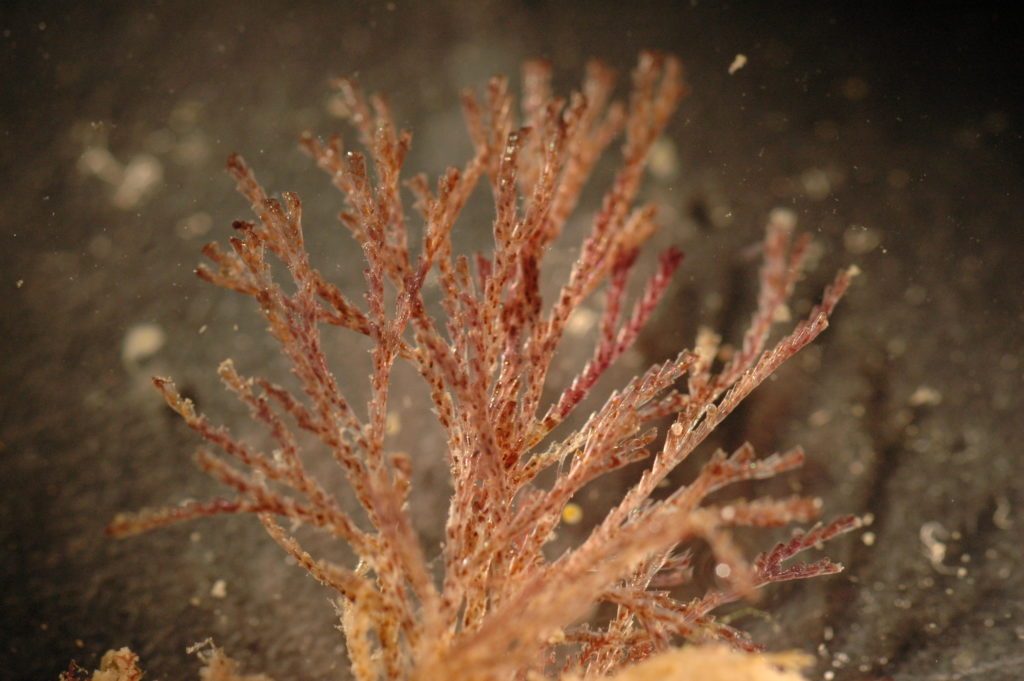

The newly discovered invasive bryozoan, Bugula neritina. (Melissa Frey/Royal BC Museum)

Ketchikan, a town of about 8,000 people on the southern tip of Alaska, is a gateway to more remote Alaskan waters in the north. It sits fewer than 100 nautical miles from British Columbia, so invasive species travelling from southern ports are likely to appear in Ketchikan first. But detecting marine invasive species is a constant challenge, even in a single harbor. By collaborating with citizen scientists from Ketchikan, Smithsonian researchers were able to document these new invasive species hopefully as soon as they arrived.

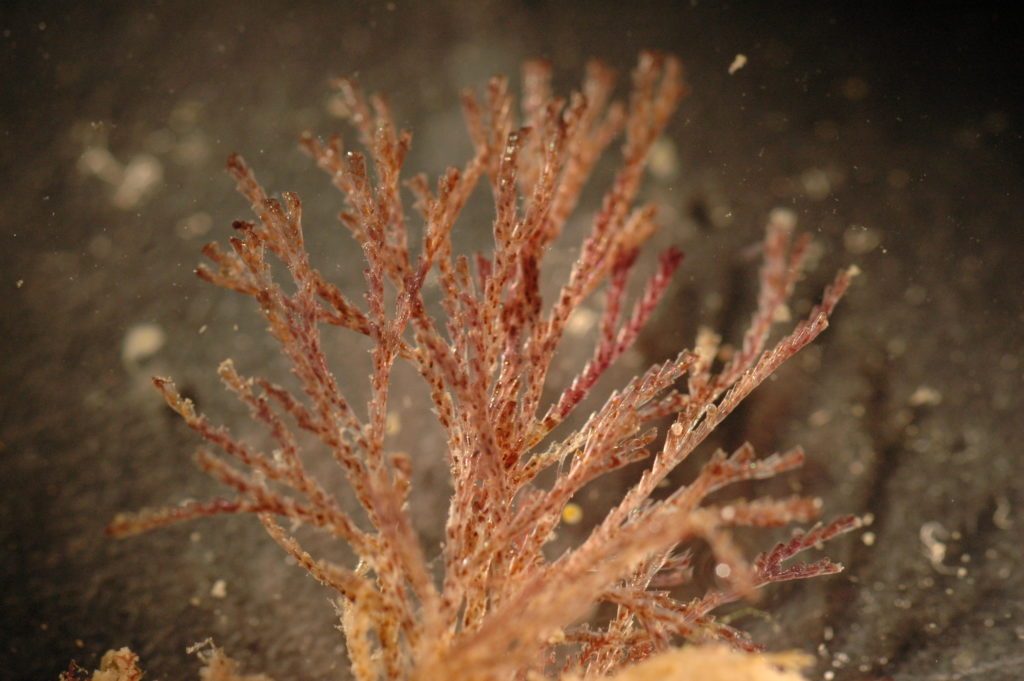

The invasive tunicate Botrylloides violaecus has nearly completely covered this crab’s shell. (Gary Freitag/University of Alaska Fairbanks)

“It’s really important to know when new non-native species show up. They may be tiny invertebrates, but they can create big problems,” said lead author Laura Jurgens, who was a SERC postdoc at the time of the study. “Early detection means you have a better chance of controlling them before the populations get established. In other places, like California, Oregon and Washington, these organisms have displaced local marine animals or had economic impacts by fouling boats, fishing or aquaculture gear.”

Click to continue »