by Anika Mittu, student contributor

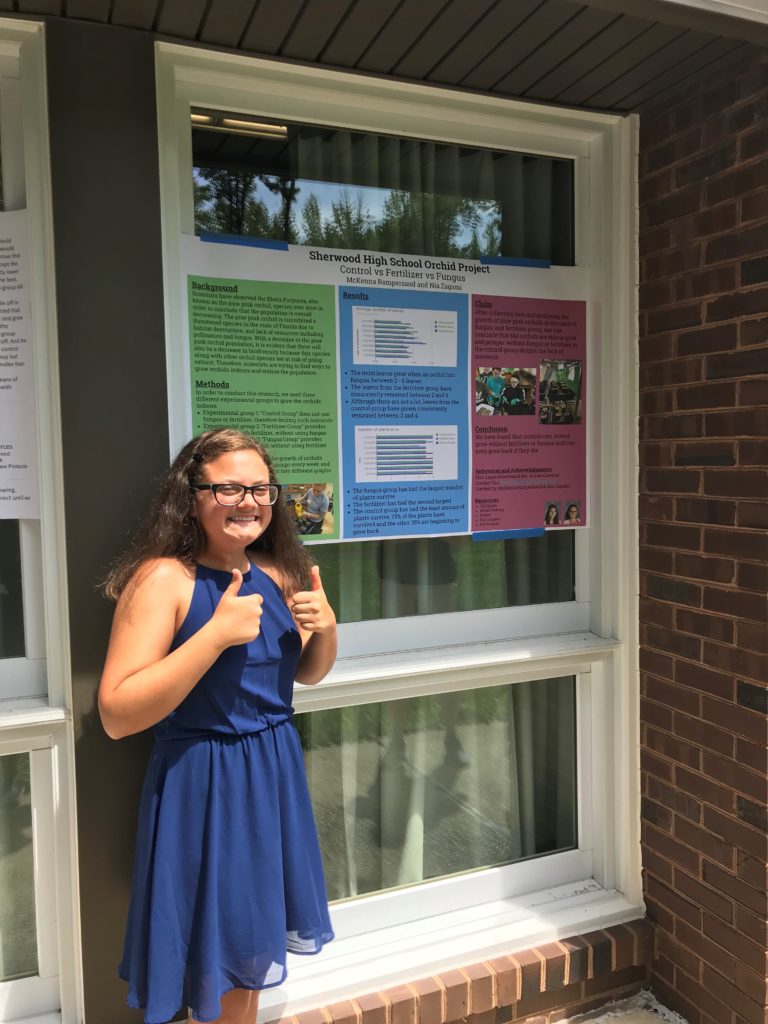

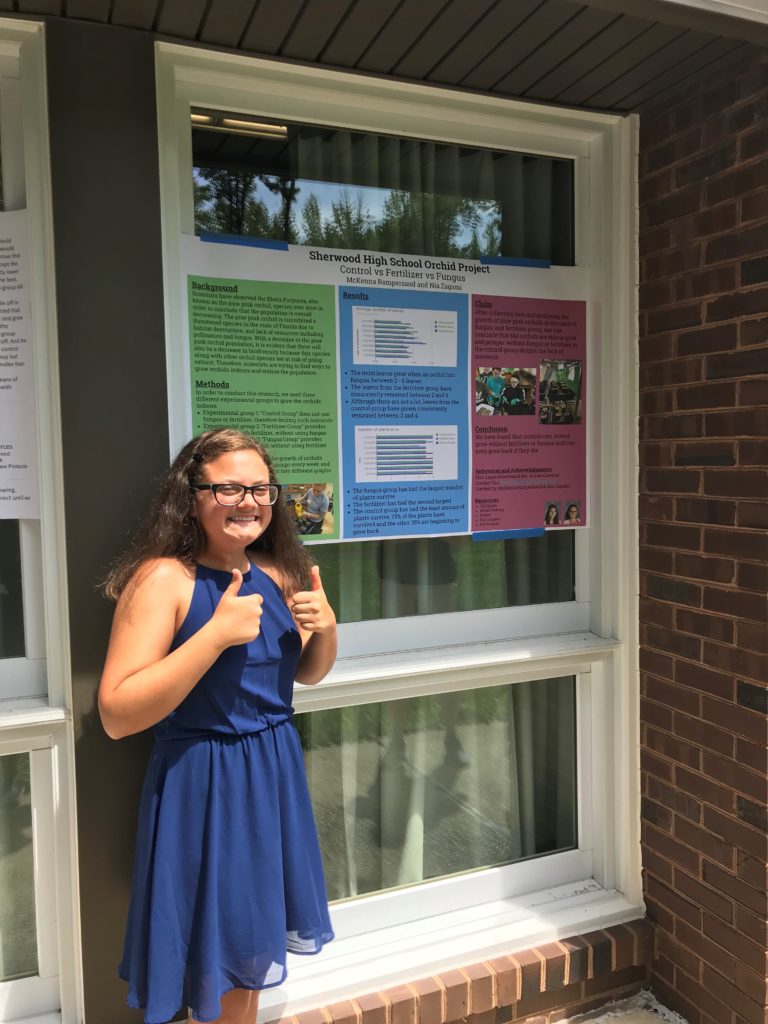

High school sophomore Nia Zagami and her classmates collected data on conserving threatened pink pink orchids, which brought her in front of an audience of scientists at the Native Orchid Conference this year. (Credit: Tony Zagami)

While preparing two students to speak at the 2018 Native Orchid Conference held at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center this summer, citizen science coordinator Alison Cawood assured them that their presentation on pine pink orchids would be low stress.

Sitting in the back of the conference room and smoothing over their dresses, the students felt otherwise.

“I feared that I would not be smart enough to share the data, and that I would mess up or look clueless,” said Nia Zagami, a sophomore at Sherwood High School and presenter at the conference. “Knowing that I was just a high schooler who was expected to speak in front of scientists and orchid enthusiasts really made me nervous.”

The nerves didn’t fade until Zagami, joined by fellow Sherwood sophomore and presentation collaborator Sudha Sudhaker, walked to the front of the conference room and adjusted her microphone multiple times. And then, the pair eased into their normal student voices to explain their own data and what citizen science means to them. An audience of blank stares began grinning.

Zagami and Sudhaker had recently finished their second semester of Honors Biology under teacher Laura Dinerman. Although Honors Biology is a common science course for underclassmen at Sherwood, Dinerman’s 60 students taking the course during spring 2018 did something decidedly less common: a professional conservation experiment. Dinerman’s class measured the growth of the pine pink orchid (Bletia purpurea). Though common in the tropics, in the continental U.S. the pine pink orchid grows only in Florida, where it’s threatened. The students grew the orchids under different soil nutrient conditions (fungi, fertilizer or unchanged soil) in their classroom, as part of a citizen science project led by the Smithsonian.

Click to continue »