by Kristen Minogue

Northern saw-whet owls are the smallest owls in eastern North America. Because of their secretive natures, for a long time scientists didn’t even know they migrated. Project Owlnet is changing that. (Credit: Carl Benson)

Melissa Acuti is a chronic gambler. But the wagers she makes don’t involve casinos, poker chips, slot machines or even money. Instead, she’s willing to sacrifice hours of sleep checking nearly invisible mist nets in the forest. The prize: A tiny saw-whet owl, the smallest (and arguably cutest) owl in eastern North America.

“Everybody has that—playing the lottery, Bingo, that little, ‘I might win,'” Acuti said one frigid November evening in 2017. “This is my ‘I might win,’ when I catch an owl.”

By day, Acuti works for the Maryland Department of Natural Resources. But for four to six weeks in October and November, when saw-whet owls begin their migrations, she stays up until midnight or later to band them. It’s part of a continent-wide effort called Project Owlnet, in which scientists attach tiny bracelets to the owls’ feet to track their journeys. For the last two years, Acuti has run a Project Owlnet station at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) in Edgewater, Md., and convinced dozens of citizen scientists to join her.

“Just the anticipation of what you might find is very exciting,” said Lenore Naranjo, who joined Acuti for six nights this year with her husband, Ralph. “And the camaraderie of everybody waiting and tromping out together to look and check.”

Drawing the Owls Out of Hiding

Credit: Carl Benson

Saw-whet owls are barely the size of a human hand, with golden eyes, chocolate-brown feathers and faces that have inspired some to call them “kittens with wings.” However, catching one is no easy task. For all their cuteness, saw-whet owls are extremely secretive. Even avid birders rarely see them in the wild. Hearing them is a long shot too, as their high-pitched cries typically echo only during spring breeding.

Setting up a station like Acuti’s requires a permit from the U.S. Geological Survey’s Bird Banding Laboratory and extensive training for the leaders. In mid-autumn, at the beginning of their migratory season, Acuti sets up nets in the SERC forest. They’re rolled up during the day, so nothing will fly in while the sun is up. Starting at sundown, she and the evening’s volunteer crew unfurl them. The nets’ strands are thin and wispy, making them nearly invisible in the dark and giving them the ethereal name mist nets.

But owls won’t simply fly into the nets by chance. Something needs to lure them in. That lure is the mating call of a male saw-whet owl, played on a recorder fastened to a nearby tree. Acuti admits it’s a bit strange females would respond to a male call in autumn, when their breeding season is in spring. But past experiments have shown nets catch more owls when they use the recording.

“It shouldn’t work, but it does,” she said.

These feathers are from a young “hatch-year” owl still in its first year of life. Its feathers all flouresce pink under ultraviolet light, which means they’re new. (Credit: Mackenzie Carter/SERC)

If the group gets lucky and captures an owl, they take it back to the Reed Education Center to measure it, weigh it and determine its sex. They also estimate its age, by shining a special “black light” flashlight on its feathers (younger feathers fluoresce pink under the flashlight’s ultraviolet light). Then they put a silver band around its ankle with a number and release it back into the wild.

The ultimate jackpot, Acuti said, is catching an owl that already has a band. When that happens, the researchers can look online at the Bird Banding Laboratory and see when and where the bird was caught before. Catching the same bird multiple times allows researchers to piece together its journey, the ultimate goal of Project Owlnet.

“When you catch an owl that’s already been banded by somebody else, it’s like the winning lottery ticket right there,” she said.

The First Year

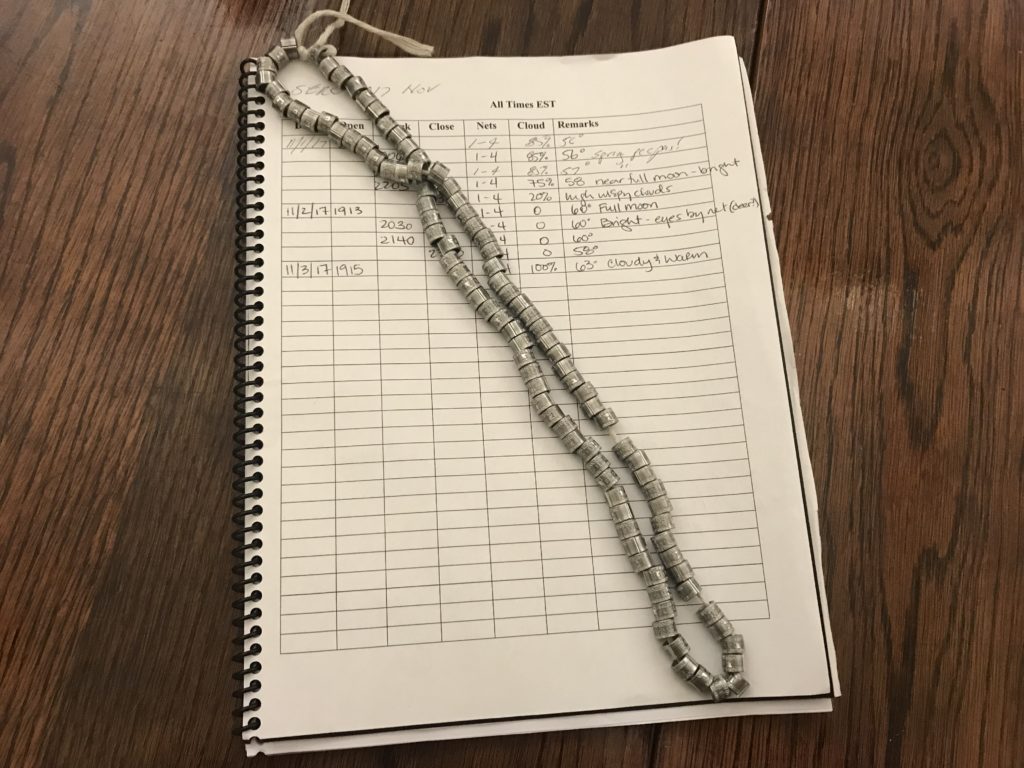

Whenever Project Owlnet scientists catch an owl, they put one of these silver bands around its leg. (Credit: Kristen Minogue/SERC)

Project Owlnet began in Maryland in 1997. Today, over 100 stations band owls across the U.S. and Canada. Operating for more than two decades means scientists have started to piece together some of the mysteries surrounding these elusive birds. They’ve caught females and younger (“hatch year”) owls migrating most often, which could mean males are more likely to stay north to stake claims on their breeding territory. (Or, Acuti points out, it could just mean females respond more often to a recording of a male.) They’ve also tracked the owls as far south as Georgia and Alabama, territory some thought beyond their range.

When SERC joined in fall 2017, it was yet another gamble. Alison Cawood, the center’s citizen science coordinator, encouraged Acuti to bring Project Owlnet to SERC after joining one of Acuti’s owl banding nights on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. But with two large cities—Baltimore and Annapolis—to the north, SERC did not seem like the most likely place to find saw-whets.

“If I were a little tiny owl, I don’t know that I’d go through Baltimore City,” Acuti said.

That first year, it would be tempting to think the gamble hadn’t paid off. Acuti and the volunteers stayed up for 21 nights and netted a total of seven owls. (Technically the lure worked eight times, but one owl flew into the nets twice.)

SERC wasn’t alone. 2017 was exceptionally slow all across Maryland. Assateague, one of the first Project Owlnet stations, netted a grand total of two unique owls—its lowest in 27 years.

“Not too many people made it past a single digit,” Acuti remarked.

But volunteers turned out in droves.

“They’re just downright cute,” said Lloyd Lewis. A retired oceanographer turned bird enthusiast, Lewis has volunteered at various Project Owlnet stations since the early 2000s. “I don’t usually call things cute. I’m kind of a cantankerous old fool.”

So the next fall, Acuti brought back her nets and her recorder and prepared to try again.

Melissa Acuti (left) and volunteer Kathy Fuller pose with saw-whet owls. (Credit: Chuck Fuller)

The Irruption Year

On Oct. 24, the fourth night of the banding project, Acuti’s team caught their first owl of 2018. An encouraging sign, to be sure, but not necessarily an omen of a better year. After all, they’d caught their first owl on the fourth night of 2017 as well. But Acuti had heard rumors from further north, where stations begin banding owls in September, that saw-whets were coming out in higher numbers. So she remained hopeful.

Over the next two weeks, the team had sporadic success, with a few more nights finding one, two or occasionally three owls in the nets. Then, on Nov. 8, they truly hit jackpot.

An unprecedented 24 owls flew into their nets that night. Acuti and her volunteers barely had enough time to weigh, measure and release one batch of owls before they had to return to their nets for the next scheduled check.

“I’m pretty sure that it was the good weather that night,” Acuti said. She suspected a cold front a few nights earlier had encouraged many saw-whets to hunker down, and then they all took off as soon as it let up. “The floodgates open because these birds have gotten bottled up further north waiting for the wind to change direction….It was like everything happened at once.”

Many other stations also saw a bonanza on Nov. 8. Some sites that stayed open until sunrise caught over 100 owls. While that particular night topped the charts, the momentum continued for the rest of the season. By the time Acuti’s team closed their nets for the year the night before Thanksgiving, they had banded a total of 54 owls.

Left to right: Melissa Acuti, Madeline Rivard, Jonathan Huang, Mackenzie Carter and Sarah Lank take an owl selfie in November 2018. (Credit: Mackenzie Carter/SERC)

Birders call years like 2018 irruption years. Not like volcanic eruptions, where something explosive bursts out, but a time when a vast number of things (or creatures) rush in. The last irruption year in the Northeast was in 2012. In general, scientists thought saw-whet owls peak roughly every four years based on the weather and their food supply. But Mother Nature is known for not always following the rules.

“Of course, nature doesn’t read any of these scientific publications saying it should follow a four-year cycle,” Acuti said.

Lenore Naranjo is still waiting to catch her first owl. After she and her husband, Ralph, volunteered six nights at SERC, Ralph finally saw one on the seventh—a night Lenore wasn’t able to join. It’s a testament to the pull of these tiny, kitten-faced birds that Lenore and Ralph both plan to return and play the odds again in 2019.

“Maybe one of the times I’ll be lucky,” Naranjo said. “I won’t give up.”

Want to join Project Owlnet at SERC in 2019? Email Alison Cawood at cawooda@si.edu to be added to our citizen science email list, and get updates on when the project will start next year!

From an Eaglecam and zoocam lover these photos of the saw-whet owl make me smile. They have to be the cutest birds I have ever seen. Wow, good work to all the scientists and volunteers for tracking and tagging them.