by Laila Hurd

Though currently a volunteer with the Chesapeake Water Watch project, this is not Maria Alejandra Ceballos’ first rodeo at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC). Thirty years ago, Ceballos spent her summer interning at SERC’s Photobiology and Solar Radiation Lab with Pat Neale. Since then, she has made a career studying water quality and ecology, combining her passion for the outdoors with scientific pursuits.

Same Data, New Tech

For her internship in 1993, Ceballos measured atmospheric clarity and UV light to compare her data with data from satellites. This process is part of “ground truthing,” which confirms whether a satellite’s reading matches a reading from the ground. Using measurements of atmospheric clarity, scientists can correct satellite images to how they would appear if taken at ground level. Today, digital technology makes it easy for volunteers to make these measurements for the Chesapeake Water Watch project. But in the 90’s, the technology looked much different.

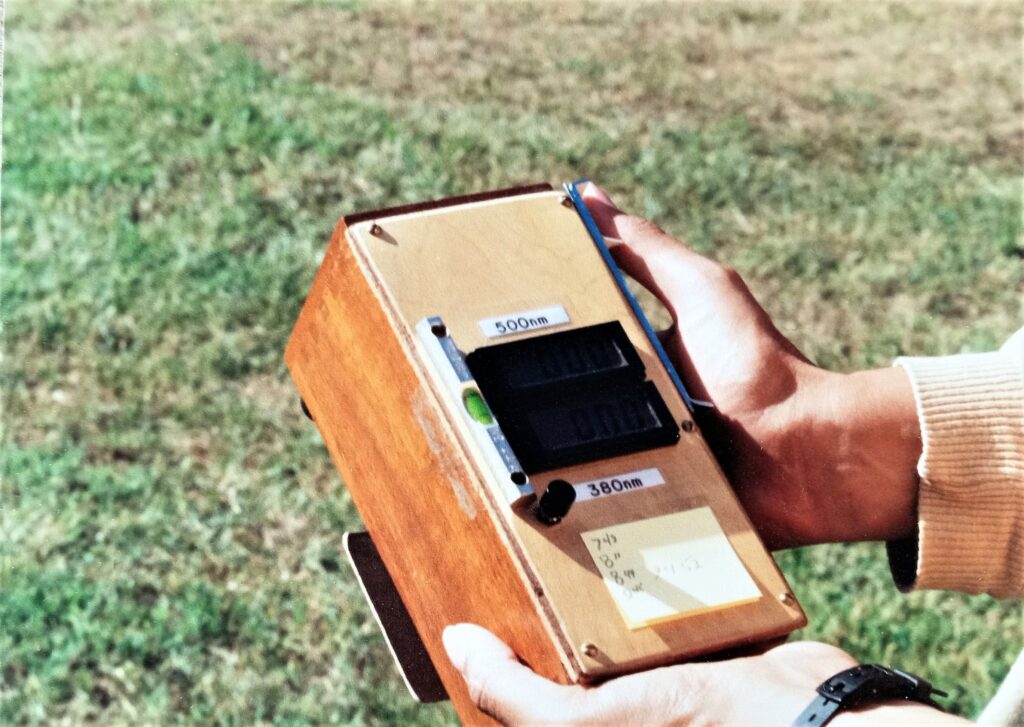

“She made the measurements on what was called the sun photometer,” Neale said—or a little brown box with two buttons. “The instrument was constructed by the Smithsonian because there weren’t a lot of commercial instruments available at that time.”

Ceballos remembers well the patience required to use it. She had to hold very still while pointing the box at the sky at 7am or 9am, and throughout the day. A spreadsheet informed her what time of day to take data based on the angle of the sun.

“I had a watch, you had to set it [the alarm], and then I would run out to the same spot and take the reading,” Ceballos said. “We would use data from the satellite that came on a floppy disk. Then we would have to download it on the computer. . . There were a lot of steps that today you don’t have to do.”

The Calitoo sun photometer now automates these steps, so measuring atmospheric clarity is much easier. Similarly, the Chesapeake Water Watch project invites participants like Ceballos to use the smartphone app HydroColor. The HydroColor app asks users to take pictures of the water and sky with their smartphones. It then reports an estimate of water clarity. The data is then uploaded to a publicly accessible database on a computer. Satellite data is easy to take in the open ocean, but not in nearshore habitats like the Chesapeake, making the HydroColor data crucial for tracking the health of the Bay.

“Science has come a long way, which is what’s interesting about this citizen scientist program,” Ceballos said. “Back then, having access to radiometers or photometers wasn’t something any citizen could do.”

Volunteer Science in the Bay and Beyond

The Chesapeake Bay has supplied Ceballos with plenty of opportunities to continue her field work on sediments, nutrients and water ecosystems. Her experience at SERC was memorable enough to convince her to move to Maryland in the 2000s. The Chesapeake Water Watch project fit Ceballos’ image of accessible science, as she can use HydroColor near her home in southern Maryland on local tributaries.

“I believe in volunteering wholeheartedly, and have been doing it since I was in my early teens through adulthood,” she said. “I find rebranding it as citizen or community science really empowers the volunteer as an integral part of the team.”

Outside of the Chesapeake Water Watch project, Ceballos has involved herself in other volunteer projects. She has spent a decade participating in the Patuxent River Terrapin Nesting Survey. The survey monitors turtle nesting sites and releases turtle hatchlings with the goal of tracking their population demographics. The project requires volunteers to hike once or twice a day to monitor the nests.

Additionally, Ceballos took her studies beyond the Chesapeake Bay to gather water samples in Iquique, Chile. She even ventured out to the frigid Bering Sea to collect mud samples for her lab.

“I got to be on an icebreaker in 2009, to do the same thing I do in the Bay, but in minus 40 Fahrenheit degree weather….It was awesome” Ceballos said. “These projects highlight that volunteers can make a difference on a local and global scale, and that finding ways to participate allows one to value both our Earth and science tangibly.”