An Ecological History of SERC-West’s California Home

By Ryan Greene, science writing intern

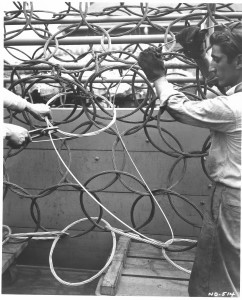

A naval net depot was one of the many institutions to occupy the site on the San Francisco Bay where the Romberg Tiburon Center for Environmental Studies now operates. Photo courtesy of the Tiburon Landmarks Society and Romberg Tiburon Center. [Cropped]

The Romberg Tiburon Center for Environmental Studies (or Romberg Center for short) sits on a 36-acre parcel of waterfront land whose history is rather kaleidoscopic. Depending on when you were here, you could have found a cod packing plant, cables destined for the Golden Gate Bridge, or multi-mile antisubmarine nets. And this is just a smattering.

The Romberg Center is a research and teaching facility run by San Francisco State University. Nearly two decades ago, in 2000, SERC ecologist Greg Ruiz stationed part of his Marine Invasions Lab here. Since then, this outpost has become the hub of SERC’s West Coast ecological research. In addition to Smithsonian and San Francisco State biologists, the Romberg Center is also home to members of NOAA’s San Francisco Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve. Together, these institutions use the historic site as a base for exploring the Bay’s ecology. This, though, is only the most recent in a long line of land uses. And looking more closely at what people have done here in the past can provide a glimpse into a host of ecological issues still shaping San Francisco today.

The early days:

Kule Loklo (i.e. Bear Valley) is a recreated Coast Miwok village at Point Reyes National Seashore, north of San Francisco. It was constructed by the Miwok Archaeological Preserve of Marin and the National Park Service in the 1970s. Credit: Stepheng3

For thousands of years, the Coast Miwok people and their ancestors have lived in what is now Marin County. Today they are part of the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, a federation of Coast Miwok and Southern Pomo groups. Back before European colonization of the region, Coast Miwok villages dotted the Tiburon Peninsula, where the Romberg Center now operates. In those days, the Coast Miwok people fished, hunted, and gathered their food, relying heavily (but not exclusively) on aquatic plants and animals. Women collected crabs, abalone, limpets, oysters, mussels, and clams, while men fished with hooks, nets, and woven traps. They gathered kelp as well, which they ate fresh and also dried for the winter lean months.

Starting in the mid-1500s, successive waves of European exploration and colonization began to leave their marks on what became known as Alta California (upper California). The newcomers brought with them new plants, animals, and cultures, and by the late-1700s, Spanish missions starting popping up. About 10 miles north of the Romberg Center’s current site, Spanish Franciscans built Mission San Rafael Archangel in 1817, which dramatically impacted the Coast Miwok people living in the surrounding areas. Four years later, in 1821, Alta California left Spanish rule when Mexico won independence from Spain.

In the following decade, Irish immigrant John Reed acquired the Tiburon Peninsula as part of the Rancho Corte de Madera del Presidio land grant (1834). Though the ownership rights were thrown into question after the United States wrested control of California from Mexico during the controversial Mexican-American War (1846-1848), Reed’s heirs eventually secured legal recognition of their inheritance and used the land to ranch cattle.

Tule elk were hunted to extinction in Marin county in the years after the Gold Rush. Over a century later, federal and state agencies successfully reintroduced them to the region. Credit: Austlee; CC license https://tinyurl.com/q9q73p5

Cattle grazing transformed the California landscape. Domesticated animals like cattle, horses and sheep had existed in California since Spanish and Russian colonists brought them over. But after Mexico’s independence, cattle grazing took off, thanks to land grants like the one given to Reed. Soon, non-native grazers like domestic cattle began to replace native grazers like the tule elk, which were hunted to extinction in Marin County in the years following the 1848 Gold Rush. This shift in grazing, combined with the introduction of new plant species from Europe, dramatically changed the face of California’s coastal grasslands.

Over the years, individuals and businesses bought up parcels of the Rancho Corte De Madera del Presidio. In the 1870s, the Lynde & Hough company purchased the deepwater cove where the Romberg Center now stands. Here they established their Pioneer Fish Warehouse of the Pacific Coast—the first in a long line of industrial, military, and academic institutions that would occupy the site.

From Cod to Coal:

Lynde & Hough’s warehouse was a West Coast giant of codfish curing, packing, and shipping. In the late 1800s, San Francisco was the only West Coast port with a Pacific cod fishery. At that time, Atlantic cod was quite expensive because it needed to be shipped from the East Coast. This meant crossing the isthmus of Panama (no canal yet!) or sailing all the way around Cape Horn at the southern tip of South America. When Pacific cod was discovered off the coast of Alaska, the West Coast cod game changed big time.

Schooners moored in the deepwater cove delivered Pacific cod to the Lynde & Hough processing warehouse. Photo courtesy of the Tiburon Landmarks Society and the Romberg Tiburon Center. [Cropped]

In 1904, the Lynde & Hough company sold the property to the government, and it became a coaling station where the Navy stored coal and refueled its ships for the next 30 years. This operation significantly altered the cove’s shoreline—the Navy filled the cove in, covered it with concrete, and built a seawall. On this new solid ground, they erected a titanic trestle, part of which remains standing to this day.

Coal wasn’t the only natural resource that made its way to the filled-in cove. Throughout the 1920s, shipments of California’s famous North Coast redwood lumber were stockpiled at the station before heading east on larger vessels. This, though, was rather short-lived, because when coal gave way to oil as the fuel of choice for ships, the Navy shuttered its operation and loaned the site to the State of California in 1931.

The coaling station used East Coast coal to fuel Navy ships. Eventually, the Navy filled in the cove entirely and covered it in concrete. A portion of the trestle in this photo still stands today. Photo courtesy of the Tiburon Landmarks Society and the Romberg Tiburon Center.

From Cables to Nets:

Workers assemble anti-torpedo net mesh. Photo courtesy of the Tiburon Landmarks Society and the Romberg Tiburon Center.

For the next decade, this is where the state ran its first nautical training school, which would later become the California Maritime Academy. During this time, the John A. Roebling’s Sons company used one of the warehouses on site to wind and reel steel cables for the Golden Gate Bridge.

By 1940, WWII loomed large and the Navy reclaimed the site to establish its Naval Net Depot. Personnel at the base assembled, shipped, and deployed antisubmarine and anti-torpedo nets meant to safeguard harbors along the West Coast and across the Pacific. Most memorably, they strung a 7-mile, 6,000-ton antisubmarine net across the entrance to San Francisco Bay, which was in position by the day Pearl Harbor was attacked—December 7, 1941. Although the nets were recalled after the close of the war, the depot was revived in the early ’50s during the Korean War. It wasn’t until 1958 that the depot shut down for good, and two parcels of the naval base were converted into public parks: Tiburon Upland Nature Reserve and Paradise Park. The large concrete weights from the nets now form parts of the seawalls at the Romberg Center and Paradise Park.

A turn toward research:

In 1961, the U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife established the Tiburon Marine Laboratory, a research center focused on fish migration, pesticide impacts, and sea-surface temperature monitoring. This came at a time when public outrage against plans to fill in large swaths of the Bay for development was changing how people viewed our relationship to nature’s resources. No longer was the Bay seen simply as a place to dump garbage and drain sewage—it was considered an ecologic and aesthetic resource worthy of protection.

The Tiburon Marine Laboratory was but the first of many organizations to use the site as a hub for marine and estuarine research over the next two decades. Often multiple groups shared the space. Some researchers studied how petroleum components impacted fish, others conducted environmental assessments of proposed coastal development, and still others gave advice to fishermen on how to catch and process certain species that were not typically fished.

In 1978, San Francisco State University entered the story when its president, Paul F. Romberg established the Tiburon Center for Environmental Studies. For a number of years, the new institution shared the site with NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service. Now the Romberg Center works with SERC-West and the San Francisco Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve to unravel the ecological mysteries of San Francisco Bay.

In the early 2000s, the Romberg Tiburon Center cleaned up much of the debris from the Naval Net Depot, including discarded nets and unused cables. Credit: John Kern/RTC

In the past half-millennium, this bit of land has passed through many hands and has served a wide range of uses. These days, the scientists at SERC-West are taking advantage of the waterfront location to keep track of how global shipping and other human activities are changing the makeup of species in San Francisco Bay. As always, the ecology of this place is in flux. Now, though, the researchers here have the chance to watch things unfold in real time.

***

Further Reading/Sources:

***

Romberg Tiburon Center webpage about the site’s history:

http://rtc.sfsu.edu/about/history.htm

Archival photos of the site:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/rombergtiburoncenter/sets/72157634308729543/

A 1982 NOAA report about the site’s history:

https://swfsc.noaa.gov/publications/FED/00164.pdf

Article about the site by former Tiburon town historian Branwell Fanning:

http://tiburonheritageandarts.org/the-romberg-tiburon-center/

More information on Coast Miwok people and Native American history and culture in the Marin area:

http://www.gratonrancheria.com/culture/

https://www.nps.gov/pore/learn/historyculture/people_coastmiwok.htm

http://www.mapom.org/index.html

http://www.marinindian.com/about.html

Early California history including European exploration and colonization:

http://www.encyclopedia.com/history/united-states-and-canada/us-history/alta-california

History of the Lynde & Hough codfish processing plant:

http://rtc.sfsu.edu/about/documents/RTC_baysideFall_2016_Flipbook/mobile/index.html#p=7

1895 article about the Lynde & Hough processing plant:

https://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=SFC18950809.2.126

Information about the Naval Net Depot:

http://californiamilitaryhistory.org/Tiburon.html