by Ryan Greene, science writing intern

SERC ecologist Chela Zabin (left) with artist Tanja Geis (right) at Geis’ exhibit at the Embark Gallery in San Francisco on July 17, 2017. They are standing in front of Geis’ piece “Layer Cake,” a drawing of an experimental native oyster restoration reef painted using pigment from the mud in San Francisco Bay. Credit: Ryan Greene/SERC

This summer, Oakland-based artist Tanja Geis teamed up with Smithsonian researchers for her multimedia exhibition, ‘Lurid Ecologies: Ways of Seeing the Bay‘ at the Embark Gallery in San Francisco. Born out of a collaboration with scientists at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center’s Tiburon laboratory, ‘Lurid Ecologies’ explores efforts to restore the Bay’s only native oyster, Ostrea lurida. Geis works at the intersection of visual art and ecology. Her exhibit at the Embark Gallery includes oneiric drawings made with pigment from the Bay’s mud, a 3-channel video installation, and assemblages of tools used to study marine life. This exhibit will be free and open to the public until August 19 at the Embark Gallery in Fort Mason’s Center for Arts & Culture.

To learn more about Geis and her exhibit, check out this interview (edited for clarity and brevity).

***

When did you start making art, and why?

My mom is a fashion designer and she went to art school, and so she’s always encouraged me to make art. So, in a sense, I’ve always been making art. But I think maybe the more relevant answer is that I started taking art really seriously about five years ago. It was at that point that I realized that it was pretty much the only thing that was going to check all the boxes for me.

For the past couple months, you’ve been working alongside SERC ecologists in San Francisco Bay. Can you talk a bit about your interest in ecology and how your collaboration with SERC scientists has shaped your recent exhibit?

I’ve always been interested in the nonhuman living world ever since I’ve been a kid. I guess I’m always curious about how these little behavioral differences come together and create a functional ecology. And I’ve always had this parallel interest in biology….I’m very interested in how we conceptualize all these complex interactions that we’re calling ecology….

What surprised me most was how often things don’t go as planned. There are many dead-end experiments, and it really requires this kind of dogged will and tenacity to discover new things, new patterns, new behaviors. I think that’s something that a lot of people don’t get to see.

We have this idea of scientists in white lab coats with shiny new equipment working under fluorescent lights constantly having these new discoveries. And that’s really not the case. Ecological research is messy, it’s muddy, it’s full of things you can’t control.

A still from Geis’ video installation Life in the Greenhouse. Courtesy of the artist and Embark Arts.

Much of your past work has focused on making the “unseen” seen. Is this “unseen” aspect of scientific research what you want people to witness in Lurid Ecologies? Are there other things that you’re hoping to unveil as well?

It’s definitely that—that would be the simplest description of what the show is about. But there’s also sort of an honoring of the work that SERC does, which is their own uncovering of the unseen. And then there’s an honoring of the incredible complexity of the Bay’s ecology. For the foreseeable future, there will always be this element of mystery. I don’t think in our lifetimes we will understand 100 percent of how everything works and functions. There’s always going to be some element of the unknown… I was hoping to get at that aspect.

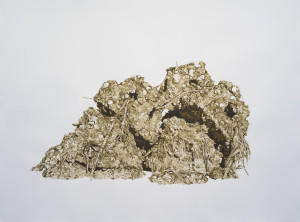

Tanja Geis, “Reef Castle,” 2017. Courtesy of the artist and Embark Arts.

Tanja Geis, “Reef Ball Stack,” 2017. Courtesy of the artist and Embark Arts.

Tanja Geis, “Layer Cake,” 2017. Courtesy of the artist and Embark Arts.

Tanja Geis, “Reef Ball,” 2017. Courtesy of the artist and Embark Arts.

For the drawings, besides literally being depictions of the structures that SERC had put up for the oysters, they also invoke something that’s both complexly beautiful but also quite dark. And a lot of those drawings are also very easily anthropomorphized. Some people were seeing eyes, and some people were seeing skulls. So something that just leaves a little room for the imagination. And the same with the videos. Some of the videos, you can definitely see what’s going on. There’s a bubble snail, there’s skeleton shrimp, there’s eelgrass, there’s a plate with oysters. But some of it is also a lot more abstract. There’s a lot of floating forms where you don’t really know what the forms are. There’s a lot of play of dark and light. So, trying to get some kind of balance between what we know and what is definable, and also acknowledging that there’s that other aspect that we really don’t know, and may never know about, which is what I think drives a lot of research, and also my own art.

Tanja Geis. “Research tools: quadrats, fouling plates, tiles, and petri dish,” 2017. On loan from SERC. Credit: Ryan Greene/SERC

Tanja Geis, “Life in the Greenhouse,” 2017. Courtesy of the artist and Embark Arts.

What is it like to work with Bay mud? Is it messy? How do you prepare it?

I actually started working with Bay mud when I was in grad school at UC Berkeley. So fortunately that was not something I had to start from zero. It took a while to get it right. But the process involves collecting mud, hopefully mud that has as few chunky impurities as possible, then running that mud through a sieve to take out any remaining gunk or twigs or organic matter that’s kind of chunky. At that point, it’s not really runny enough for my purposes, so I blend it in a blender with some water. And then I pour it out onto a slab of plaster, and the plaster sucks the moisture out of the clay. So it’s this thin layer, maybe an eighth of an inch thick on a slab of plaster, and the plaster will suck all of the moisture out.

Once it’s done drying, you have these flakes of clay. And I put these flakes of clay through a turkish coffee grinder, because that grinds it finer… and then I have a powdery clay that I can use as pigment. The binder that I use is gum arabic mostly, and then some glycerine and honey. It works pretty well! You get used to using it, and it’s less messy than you’d imagine.

Close up of ‘Reef Castle,’ (2017) showing the textured nature of Geis’ mud-derived paint. Credit: Ryan Greene/SERC

***

If you want to read more about Geis and her show, check out this review of ‘Lurid Ecologies: Ways of Seeing the Bay’ on KQED-Arts. Much of the work in ‘Lurid Ecologies’ is related to the San Francsico Bay Living Shorelines Project, which is funded by the the California State Coastal Conservancy. The footage for Geis’ video installation ‘Life in the Greenhouse’ was filmed at the Romberg Tiburon Center for Environmental Studies. ‘Lurid Ecologies’ is part of the inaugural exhibition for Embark Gallery’s ‘R&D Projects,’ which is “a series of research-intensive postgraduate fellowships and summer solo exhibitions.”