Every summer, the food web in Chesapeake Bay gets jostled around as two plankton-eating predators jockey for power: comb jellies and jellyfish. Most smaller species don’t have a stake in the battle—both predators eat zooplankton and fish eggs, after all. But for young oyster larvae, the victor could make the difference between being protected civilians or collateral damage.

Oysters and the Chesapeake’s Jellyfish Wars

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on September 30th, 2014Why 900 Years of Ancient Oysters Went Missing

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on August 29th, 2014by Kristen Minogue

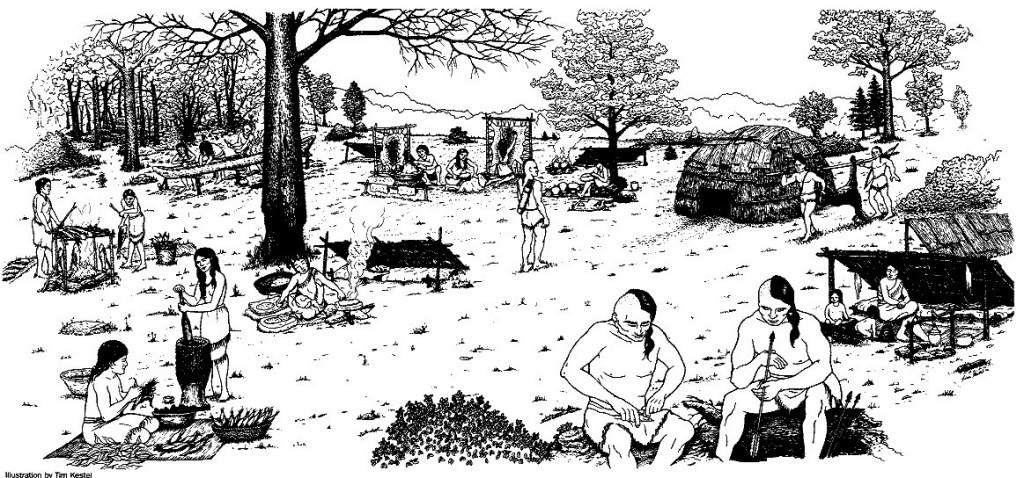

Piscataway Indians lived on the Rhode River up to colonial times, though anthropologists believe they used the land for temporary campsites, not permanent settlements.

For more than 10,000 years, Native Americans hunted and fished in the Chesapeake. Broken pottery, village sites, burial grounds and other artifacts bear witness to their near-continuous presence around the Bay. But one type of artifact—ancient trash piles called shell middens—hasn’t received as much attention. And these tell another important story.

Urban kids, urban waterways: Citizen science improves lives and environment

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on August 21st, 2014By Sarah Hansen

Tony Thomas (left), education program coordinator at the Anacostia Community Museum, supervises while students Donovan Eason (center) and DaWayne Walker run a chemical test on a water sample.

“Is the net like a Spongebob jellyfish net?” student Cristal Sandoval asked. Alison Cawood, citizen science coordinator at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC), used another analogy to explain: “It’s like a bowl with holes in it for pasta.” Light bulbs came on around the room and a knowing, “Oh,” escaped the lips of at least a dozen students.

Marshes: Pollution Sponges of the Future

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on August 21st, 2014by Melissa Pastore, biology graduate student at Villanova University

What if we could create a giant sponge capable of soaking up nitrogen pollution? It turns out that the Chesapeake Bay, which has experienced a rapid increase in nitrogen pollution from municipal and agricultural sources over the last few decades, already contains a natural version of this sponge: marshes fringing the Bay. But global change—and the nitrogen pollution itself—could change how this natural sponge operates.

Banishing the Ghosts on the Bay Floor

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on August 12th, 2014by Kristen Minogue

Every year, thousands of crab pots disappear, their lines snapped by violent storms or severed by the propellers of passing boats. Cut off from the buoys that once marked their presence, they become “ghost pots,” lost at the bottom of the Chesapeake.

But ghost pots aren’t dead pots. They’re still quite capable of trapping crabs, including mature females undergoing their spawning migration. And with no one to retrieve them, crabs too large to escape are condemned to a slow death by starvation. This often has the eerie effect of luring even more animals to their demise, says Laura Patrick, aquatic ecologist at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC).

“The crabs are just going in and they’re dying,” Patrick says. “And one of the problems is that the dead animals that are in there can be bait for new crabs to come in. So it’s kind of a self-baiting pot.”

Virtual crabs could help real recovery

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on August 8th, 2014by Sarah Hansen

No one disputes that blue crab numbers in Chesapeake Bay are low. There is much discussion, however, about what to do to fix the problem. Smithsonian Environmental Research Center intern Julie Sepanik is working with SERC postdoctoral fellow Matt Ogburn to develop a computer model that will help improve our understanding of blue crab population dynamics in the Bay. The model works to identify where female crabs mature in the Bay and track their migration to lower Bay spawning areas. Ultimately, they hope the model will help inform decisions about preserving habitat and restoring the population.

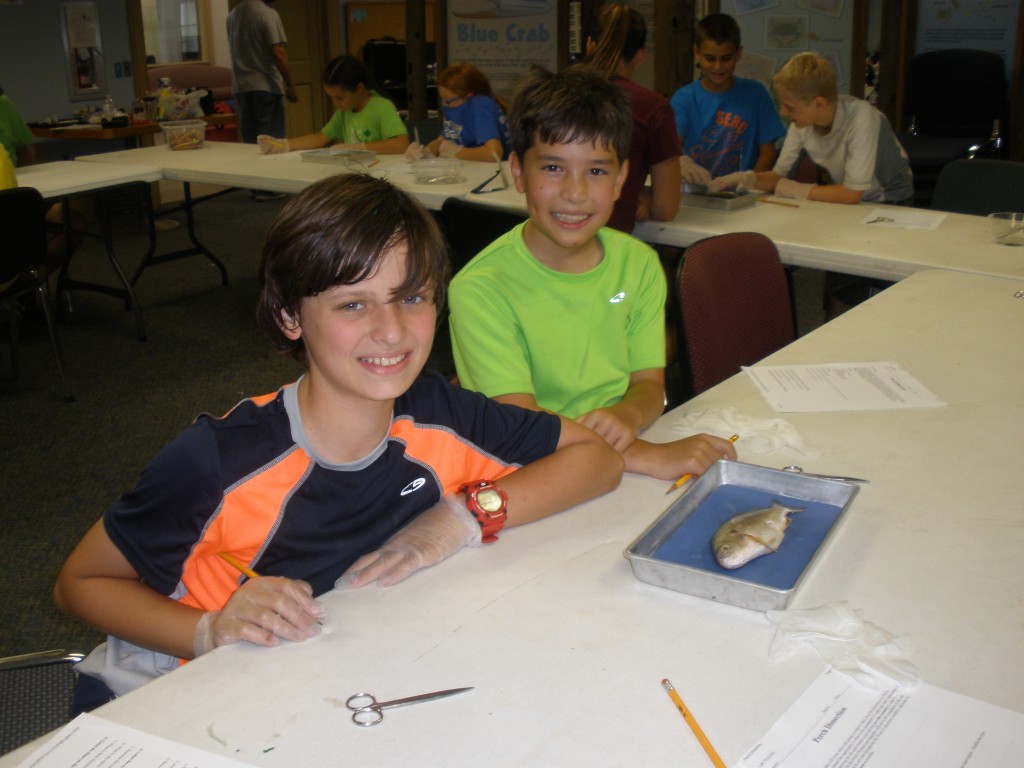

SERC camps cultivate environmentally-conscious kids

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on July 29th, 2014By Sarah Hansen

“Hurry, hurry, hurry! Baby pipefish!” camper Jack Yee, 11, squeals as he trundles across the beach in much-too-big waders with hands cupped. A moment later the startled fish, caught by campers in a seine net, is swimming safely in a plastic tub already populated with silversides, glass shrimp, and one large pickerel.

Jack’s energy and concern for the creatures of Chesapeake Bay are exactly what SERC summer day camps are all about. The programs range from “Pollywogs” camp for prekindergarten students to this week’s offering, “Environmental Detectives” camp for rising fifth- and sixth-graders. Led by Education Department interns Anna Youngk, Lizzie DeRycke and Eric Glass, each week 12 children experience activities related to the Bay, its inhabitants, and what they can do to help. Click to continue »

Oysters have sidekick in Chesapeake Bay clean-up

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on July 25th, 2014By Sarah Hansen

Oyster restoration has long been championed as key to cleaning up Chesapeake Bay, because oysters’ filter-feeding lifestyle improves water quality by removing plankton. But oysters aren’t the only ones that can do the job. A new study reports that another bivalve, the hooked mussel, also removes its share of plankton from the clogged Bay. Click to continue »

Summer “Marshfest” gets all hands on deck

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on July 24th, 2014By Sarah Hansen

At first encounter, the marsh looks as if it came out of a Heinlein novel. Boxy white robots dot the wetland, igloo-shaped encampments litter the landscape, and thick black tubes snake across the mud—wait, did that one just move? On closer inspection, clusters of human beings appear crouched in the sedge, carefully taking measurements for the annual Global Change Research Wetland (GCREW) Summer Marshfest.

“These two weeks are the most important two weeks of the year for us,” said Smithsonian Environmental Research Center biogeochemist Patrick Megonigal. During Marshfest, senior scientists, postdocs, volunteer citizen scientists, interns, lab techs and visiting students all join forces to collect data for three experiments focused on climate change and nutrient cycling, all managed by Megonigal. Click to continue »

Blue Crabs Need (More Than) A Few Good Men

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on July 24th, 2014by Kristen Minogue

Male blue crabs can mate with multiple females. But with fewer men to go around, their female partners are left with less sperm to reproduce. (SERC)

The practice of selectively fishing male blue crabs in the Chesapeake—intended to give females a chance to reproduce—may have a hidden cost. A Bay without enough males could reduce the number of offspring females produce, ecologists at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center found in a paper published in the July issue of Marine Ecology Progress Series.

Maryland and Virginia began reducing the harvest of female crabs by commercial and recreational watermen in 2008, the year officials declared the blue crab fishery a federal disaster. Since then, the crabs have shown signs of a shaky recovery. But a lasting comeback hinges on females producing enough offspring to sustain the population.