by Marissa Sandoval

Julie Gonzalez, a graduate student at the University of California, Davis, holds up an invasive European green crab. (Credit: SERC)

In an artificially created estuary near San Francisco Bay, called Seadrift Lagoon, a very real problem arose when European green crabs (Carcinus maenas) arrived in the 1990s. After taking up residency, the invasive species population grew immensely as the crabs feasted on Dungeness crabs, clams, and oysters—a grim problem for the native animals and migratory shorebirds that rely on them.

The stark situation demanded major intervention. In 2009, researchers from the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC)’s Marine Invasions Lab, the University of California, Davis, and Portland State University partnered to eradicate the local European crab population through intensive trapping.

But their efforts accidentally led to even more green crabs. Now, over a decade later, the teams who addressed the problem head-on have published a paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on what they learned from a conservation effort gone awry. Led by Ted Grosholz of the University of California, Davis, the new study advocates for major caution when working with invasive species whose life history is similar to European green crabs.

“Eradication has often been seen as the ultimate gold standard in invasive species management. But complete removal is like getting the toothpaste back in the tube,” said co-author Andy Chang, ecologist and program leader for SERC’s marine invasions research in San Francisco. “We’ve learned how important it is to tailor management strategies and goals to the species and the situation.”

Lessons from the Field

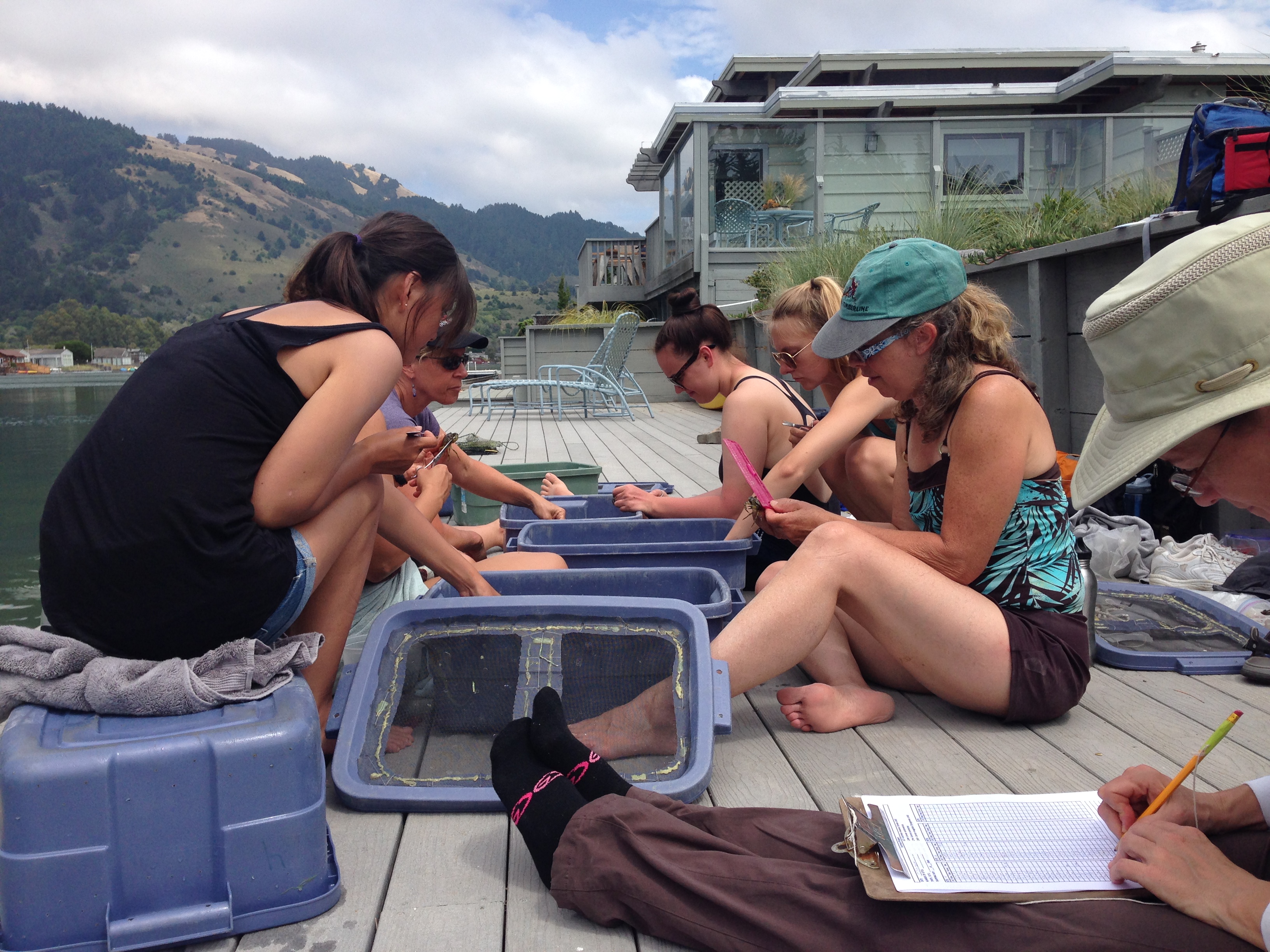

SERC biologist Linda McCann (right, blue cap) works with a team of staff and interns measuring green crabs. (Credit: SERC)

Starting in 2009, scientists and volunteers set out and collected traps tirelessly each summer, measuring and recording information for each European green crab. After removing them from the lagoon, the team donated the crabs to a local farm where their high amounts of nitrogen and calcium could serve as fertilizer.

From the recycling of nutrients to the reduction in crab numbers, the effort appeared to pay off. The size of the population had decreased from 125,000 crabs in 2009 to less than 10,000 in 2013. The crew had eliminated over 90% of the invaders.

So you can imagine the surprise when, in 2014, the scientists found themselves with 300,000 adult European green crabs! How could the crab population possibly have exploded 30 times higher in only a year’s time?

Did other crabs migrate from nearby estuaries? Did other regions in California observe similar trends? Or was another phenomenon at work?

The Cannibalism Conundrum

A collection of invasive green crabs. Adult green crabs cannibalize younger ones, a phenomenon that had helped keep their numbers in check. (Credit: SERC)

By all observable metrics, the aggressive approach should have done the trick. But the research teams soon discovered they hadn’t been looking at the right thing.

What’s not apparent to the naked eye are baby European green crabs. As larvae, the crabs swim among the plankton, so small you’d need a microscope to count their legs. These were the little buggers that had likely abounded by the hundreds of thousands in 2013. And in their newly published paper, the researchers explain how they confirmed the 10-legged baby boomers were responsible for the population explosion.

Closeup of a European green crab, Carcinus maenas. You can identify them by the five spines on either side of their eyes and a mottled olive-green carapace. (Credit: SERC)

Cannibalism among these crabs had helped keep the population in check. Adult crabs feed on younger ones in addition to bivalves and Dungeness crabs. But trapping methods inadvertently selected for larger crabs—namely, the adults. By removing the adult crabs, scientists were removing a major force that kept juvenile survival low. Juveniles were free to grow up with far less predation. And grow they did. Scientists call this phenomenon “stage-specific overcompensation,” where rising deaths in one age group can increase survival in another age group. Less adult crabs equals more juvenile crabs.

“Cannibalism is common in some populations of marine invertebrates,” said Chang. “Sometimes the role it plays in controlling the size of the population can be well hidden until just the right conditions come along—like a bunch of scientists unwittingly trapping all the adults!”

Three lines of evidence support crab cannibalism as the reason for the boom: First, surrounding estuaries where the teams didn’t remove crabs didn’t experience dramatic increases in crab populations. Second, researchers conducted controlled experiments demonstrating that when the size difference between juvenile and adult crabs increased, the larger crabs cannibalized more of the smaller ones. And finally, scientists compared genetic data from the Seadrift population and five other nearby lagoons and determined that the population was isolated. No mass exodus of crabs had come to Seadrift from other sites.

During their pursuit of the reason behind the boom, the research team stayed hard at work combating the crabs. Their new, more informed strategy became one of continuous monitoring and trapping, but not taking out so many adults that the crab population rebounded again.

Controlling the European green crab population has been no easy task. These feisty crustaceans serve as a cautionary tale for invasion teams to sometimes strive for management rather than elimination altogether.

Read More About Green Crabs:

Tidings From the Sunset Coast: Countin’ Crabs at Seadrift Lagoon

Small Lagoon Fights Off Occupation

As Green Crabs Invade, Alaskans Launch Counteroffensive

I really appreciate how the author, Marissa Sandoval synthesized this research. As an elementary educator, this article serves as a fantastic example of reflective practice and ever changing outcomes. The team has exposed a captivating perspective on how to manage invasive species!