by Marissa Sandoval

Many aquatic creatures live in the ballast water ships need for stability. But when ships discharge their ballast water, some of those creatures can become invasive. (Credit: Monaca Noble/SERC)

This is the first article in a three-part series which aims to explain the biosecurity concerns of ballast water and the work of the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC). Scientists in SERC’s Marine Invasions Lab have teamed up with a variety of organizations to research invasive species, on-board technology and shipping networks. The Marine Invasions Lab works from SERC’s main campus in Edgewater, Maryland, and its West Coast campus in Tiburon, California.

European green crab (Carcinus maenas), an invasive crustacean that’s caused economic and environmental problems on both U.S. coasts. (Credit: Brianna Tracy-Sawdey/SERC)

In the late 1980s, tiny crab larvae arrived in California through the water massive ships eject when they dock. The infamous European green crab had already been doing a number on the Eastern Seaboard, causing damages that would eventually reach over $22 million a year. Soon enough it was causing chaos on the West Coast as well, voraciously eating native crabs, oysters, and clams. The highly invasive crab serves as a cautionary tale of the never-ending struggles with hitchhiking marine invaders introduced via ballast water.

Ballast water is water that ships depend on to maintain stability so they’re not too top-heavy and flip over. The water fills tanks that often surround cargo. Although largely hidden during the voyage, one could watch ballast water in action at any port. When a ship loads cargo, it discharges some of its ballast water. When a ship offloads cargo, it pumps more water into its tanks.

By compensating for large weight shifts, ballast water serves an undeniably crucial role to ensure vessel safety. It also keeps the global economy running: It’s estimated that over 80% of international trade occurs via shipping. From six billion tons of goods loaded worldwide in 2000 to over 11 billions of tons in 2019, our reliance on the ocean for global trade continues to rise. But with over 10 million metric tons of ballast water coming to California each year, billions of opportunistic organisms also come threatening wildlife, ecosystems and industry.

Look What The Ships Rolled In

“When commercial vessels are not fully loaded, they carry ballast water to increase the draft and maintain stability while navigating,” said Brenda María Soler-Figueroa, a scientist with the SERC Marine Invasions Lab. “That water contains millions of microorganisms. If they survive and establish themselves in a new region, it could be really harmful.”

The impacts of these introduced species on human and ecosystem health can range from immediate to pervasive.

Diatoms, a microalgae that travels in ballast tanks, pose one of the more rare yet serious human health threats. A single diatom is no wider than a human hair or piece of paper, and seemingly harmless. But a few types of diatoms, like certain species of Pseudo-nitzschia, can cause ecosystem-wide damage when their populations explode into harmful algal blooms, and produce toxins like domoic acid.

When shellfish like bivalves, who are immune to the toxin, eat more and more of the algae in a bloom, they accumulate domoic acid. But when humans consume shellfish with the toxin, domoic acid can trigger a suite of health problems known collectively as Amnesic Shellfish Poisoning: vomiting, nausea, abdominal cramps, and even—in more severe cases of poisoning—short-term memory loss and death. Marine mammals and seabirds also experience extreme sickness after ingesting high levels of the toxin in their diets.

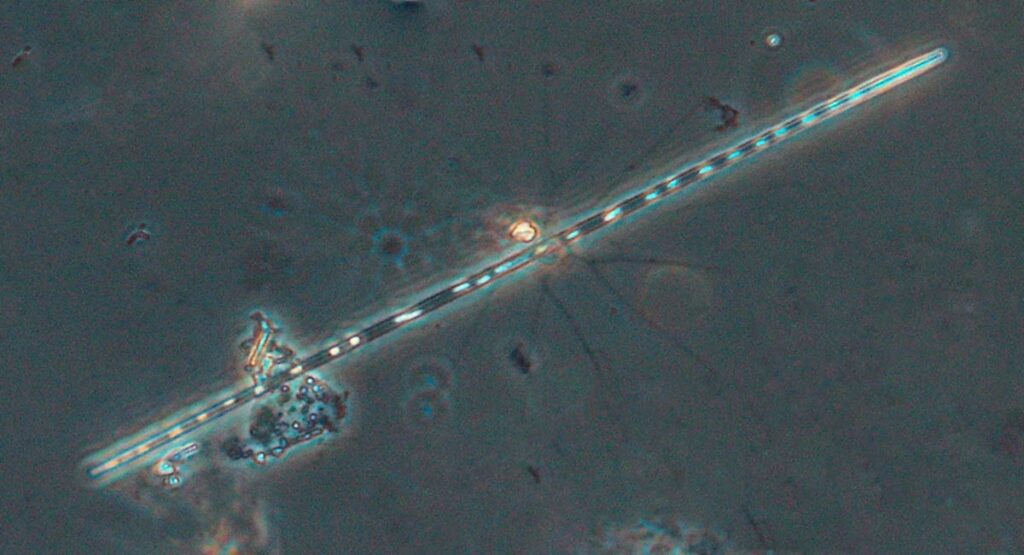

Pseudo-nitzschia lineola. This microscopic diatom can produce domoic acid, a toxin that can cause “Amnesiac Shellfish Poisoning” in humans. (Credit: Sharon Hedrick/SERC)

Less toxic, but arguably just as damaging, are macroinvertebrates like European green crabs and zebra mussels. These aggressive animals tell a different cautionary tale of marine invaders. In this story, invasive critters survive the journey traveling in ballast tanks, find a niche on a foreign coast, and begin to wreak havoc. Some invasive macroinvertebrates are incredibly good at outcompeting native species—for food, habitat and important resources like water or oxygen. It can be tricky to predict which invasives will spread or have large impacts on the environment.

Look What The U.S. Rolled Out

For this reason, the United States passed the Nonindigenous Aquatic Nuisance Prevention and Control Act in 1990. The law later evolved into the Invasive Species Act of 1996 to control existing infestations and protect coastal regions from future invasions.

Since then, the shipping industry has had to make major strides to meet expected standards. For one, ships now must manage ballast water through mid-ocean exchange or on-board treatment systems. During mid-ocean exchange, vessels pump out the water they ingested at the port and replace it with open-ocean water. This can also provide stability when it is rough at sea. The goal is to flush out any coastal organisms on board, since most freshwater organisms won’t be able to survive saltier open-ocean waters.

On-board treatment, however, uses technology to kill hitchhiking organisms before ballast water gets released at another port. Some examples include UV radiation or electrochlorination. Electrochlorination is also famous for sterilizing swimming pools and drinking water.

Additionally, scientists and local organizations are actively researching how to catch invaders early on and track them en route. SERC Marine Invasions Lab researchers have spent years tracking invasive species on board and offshore alike. From coast to coast, they’ve worked to eradicate invasive species, survey water in the ports and test ballast water technology.

International trade has increased dramatically since the first piece of legislation. But so have state and federal responses to minimize future invaders. As with most invasive species stories, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure…or a pound of crabs.

Continue Reading:

Part 2: How To Wrangle Invaders From Every Angle

Part 3: How the Supply and Demand Faucet Can Fight Invaders