by Dejeanne Doublet, terrestrial ecology intern

Ecological research usually doesn’t evoke thoughts of Stephen King horror movie scenes. Working with plants and animals in the open air shouldn’t provoke nightmares of being drenched in blood. Green is a very different color from red.

However, fellow intern Megan Palmer and I learned on our first week that sometimes, just sometimes, Stephen King references are the best way to describe a day’s work in the field. During our first days at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, Palmer and I were asked to do something that made my non-red-meat-eating stomach turn.

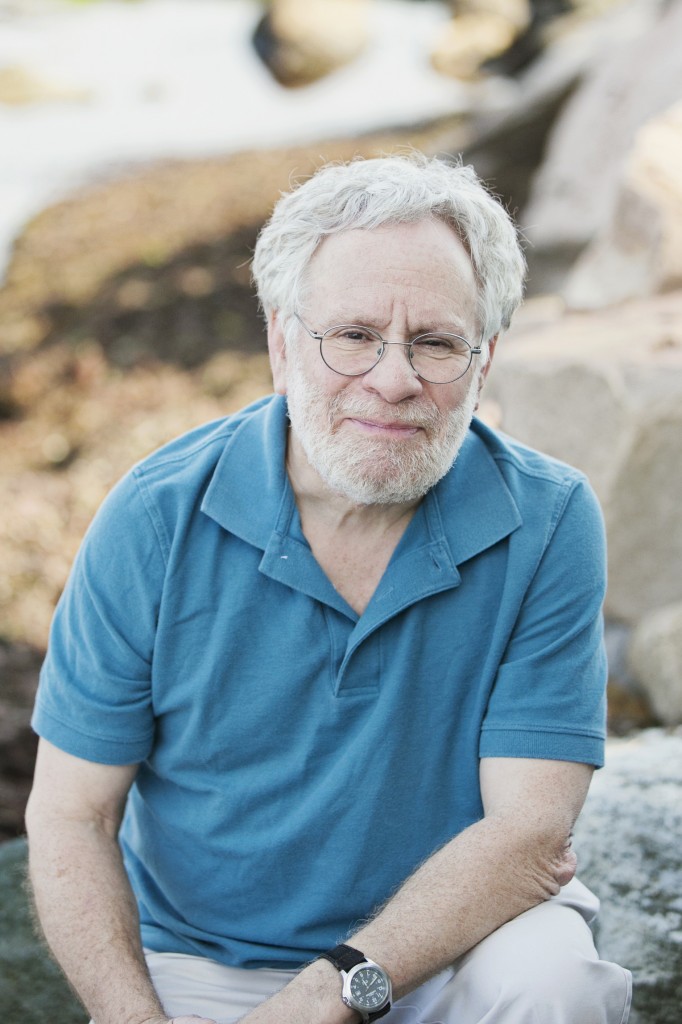

“Go spray pig’s blood on all our trees,” Dr. John Parker, the lead terrestrial ecology scientist and our boss told us during one of our first meetings with him. He was referring to the 24,000 tree saplings planted last summer as part of a 100-year experiment on biodiversity, fittingly called BiodiversiTree.