SERC Sites and Scenes

...now browsing by category

Friday, August 29th, 2014

by Kristen Minogue

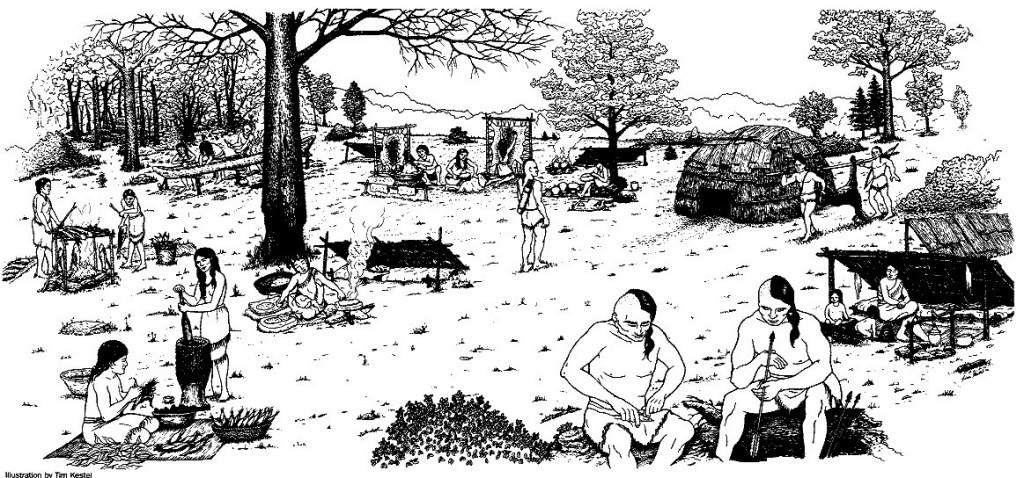

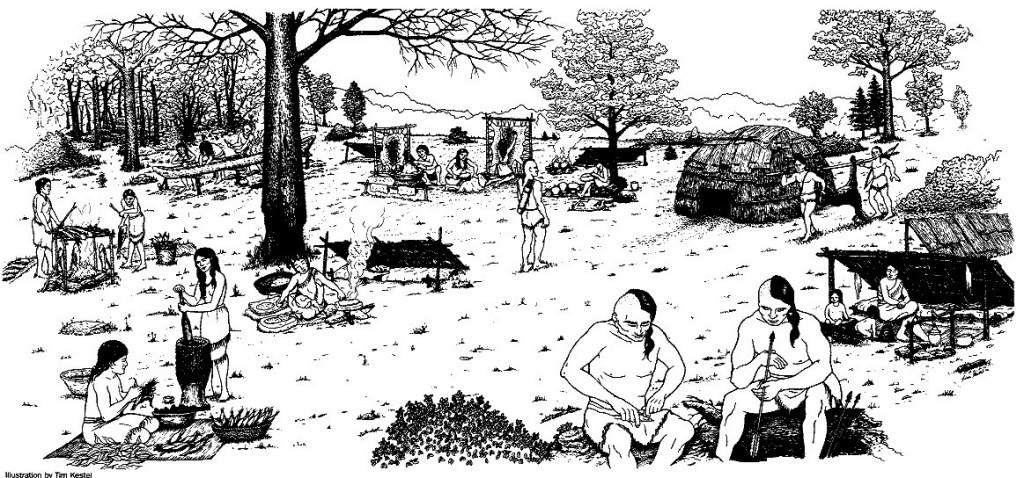

Piscataway Indians lived on the Rhode River up to colonial times, though anthropologists believe they used the land for temporary campsites, not permanent settlements.

For more than 10,000 years, Native Americans hunted and fished in the Chesapeake. Broken pottery, village sites, burial grounds and other artifacts bear witness to their near-continuous presence around the Bay. But one type of artifact—ancient trash piles called shell middens—hasn’t received as much attention. And these tell another important story.

Click to continue »

Posted in Archaeology, Climate Change, Land Use, Publications, SERC Sites and Scenes | Comments Off on Why 900 Years of Ancient Oysters Went Missing

Thursday, August 21st, 2014

By Sarah Hansen

Tony Thomas (left), education program coordinator at the Anacostia Community Museum, supervises while students Donovan Eason (center) and DaWayne Walker run a chemical test on a water sample.

“Is the net like a Spongebob jellyfish net?” student Cristal Sandoval asked. Alison Cawood, citizen science coordinator at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC), used another analogy to explain: “It’s like a bowl with holes in it for pasta.” Light bulbs came on around the room and a knowing, “Oh,” escaped the lips of at least a dozen students.

Click to continue »

Posted in Ecology, Programs, SERC Sites and Scenes, Water Quality | 2 Responses »

Tags: citizen science

Thursday, August 21st, 2014

by Melissa Pastore, biology graduate student at Villanova University

Melissa Pastore in a marsh near Delaware Bay.

(Lori Sutter)

What if we could create a giant sponge capable of soaking up nitrogen pollution? It turns out that the Chesapeake Bay, which has experienced a rapid increase in nitrogen pollution from municipal and agricultural sources over the last few decades, already contains a natural version of this sponge: marshes fringing the Bay. But global change—and the nitrogen pollution itself—could change how this natural sponge operates.

Click to continue »

Posted in Climate Change, Ecology, From the Field, Land Use, SERC Sites and Scenes, Water Quality | Comments Off on Marshes: Pollution Sponges of the Future

Thursday, July 24th, 2014

By Sarah Hansen

Experimental chambers and blowers give the marsh a spooky feel on this cloudy morning at SERC.

At first encounter, the marsh looks as if it came out of a Heinlein novel. Boxy white robots dot the wetland, igloo-shaped encampments litter the landscape, and thick black tubes snake across the mud—wait, did that one just move? On closer inspection, clusters of human beings appear crouched in the sedge, carefully taking measurements for the annual Global Change Research Wetland (GCREW) Summer Marshfest.

“These two weeks are the most important two weeks of the year for us,” said Smithsonian Environmental Research Center biogeochemist Patrick Megonigal. During Marshfest, senior scientists, postdocs, volunteer citizen scientists, interns, lab techs and visiting students all join forces to collect data for three experiments focused on climate change and nutrient cycling, all managed by Megonigal. Click to continue »

Posted in Climate Change, Ecology, SERC Sites and Scenes | Comments Off on Summer “Marshfest” gets all hands on deck

Monday, July 21st, 2014

by Dejeanne Doublet

SERC intern Dejeanne Doublet heads out to sample marsh elder.

(Megan Palmer)

As we’re knee-deep in the marsh surrounding the Chesapeake Bay, working under the relentless sun during 90-degree weather with 90 percent humidity, sweat dripping down our faces, waving off the summer bugs and trying to collect as much field data as possible, the idea of winter becomes abstract and far-fetched. It’s hard to believe we are out here in the blazing heat of summer studying the effects of this past winter— one of harshest winters this area has endured in many years.

Click to continue »

Posted in Climate Change, Ecology, Extreme Weather, Interns, SERC Sites and Scenes | Comments Off on Intern Logs: A Summer Quest

to Understand Winter

Thursday, July 17th, 2014

By Sarah Hansen

SERC intern Bridget Smith, immersed in a sea of environmental data. (SERC)

Underwater plants like sea grasses provide habitat and feeding areas for a wide range of aquatic life. They also help filter the water and put the brakes on erosion. But in Chesapeake Bay, the coverage of underwater plants, or submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV), has been low for decades, and restoration attempts have had mixed results. That’s why this summer, Smithsonian Environmental Research Center intern Bridget Smith is grappling with 28 years of data to explore which of a host of factors affects SAV in the Bay and how.

Click to continue »

Posted in Ecology, Interns, Land Use, SERC Sites and Scenes, Water Quality | Comments Off on Using Computer Models to Help Rescue Bay’s Underwater Flora

Tuesday, July 8th, 2014

by Kristen Minogue

Technician Laura Patrick holds up a blue crab caught in the Rhode River. (SERC)

This summer and fall, biologists at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center are looking to tag 10,000 blue crabs in Chesapeake Bay. They’re pursuing the project in spite of the two-year slump the crabs have suffered in the latest reports of the Chesapeake Bay Stock Assessment Committee. They’re hoping some of those crabs will help answer two unresolved questions on the path to recovery: the role of recreational crabbing, and the struggling population of adult females.

Every year watermen on Chesapeake Bay haul in between 40 and 110 million pounds of blue crabs on trotlines or in crab pots. The vast majority come from commercial watermen who rely on the crustaceans for their livelihoods. But recreational crabbers also take their share, and today no one knows exactly how large or small that share is.

“We really have very little idea how big the recreational fishery is now,” says Matt Ogburn, a postdoc at SERC’s Fish and Invertebrate Ecology Lab. Click to continue »

Posted in Ecology, Fisheries, SERC Sites and Scenes | 1 Response »

Friday, June 20th, 2014

By Sarah Hansen

An upland forest plot at SERC. Lauren Emsweller, David Gorchov, and Julia Mudd (left to right) search for five invasive plant species.

Invasive plants are rampant throughout the United States. Some have been here for tens or even hundreds of years, while others are relative newcomers. They compete with native plants for resources, and more often than not they win the fight.

David Gorchov, visiting scientist from Miami University of Ohio, is leading a project to map five invasive plant species in upland forests at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC). In particular, he’s interested in how gaps in the forest canopy, usually created by a tree falling, affect the abundance of these invasives. One of his graduate students, Lauren Emsweller, is here working on the project for her master’s thesis. Julia Mudd, a SERC intern from Florida State University, is getting college credit to help them out.

“There are a few studies that have looked at the importance of gaps, but there’s none that have done complete maps like this that I’m aware of,” said Gorchov.

Click to continue »

Posted in Ecology, Interns, Invasive Species, SERC Sites and Scenes | 1 Response »

Tuesday, June 17th, 2014

by Dejeanne Doublet, terrestrial ecology intern

Dejeanne Doublet inspects a red oak in BiodiversiTree. (SERC)

Ecological research usually doesn’t evoke thoughts of Stephen King horror movie scenes. Working with plants and animals in the open air shouldn’t provoke nightmares of being drenched in blood. Green is a very different color from red.

However, fellow intern Megan Palmer and I learned on our first week that sometimes, just sometimes, Stephen King references are the best way to describe a day’s work in the field. During our first days at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, Palmer and I were asked to do something that made my non-red-meat-eating stomach turn.

“Go spray pig’s blood on all our trees,” Dr. John Parker, the lead terrestrial ecology scientist and our boss told us during one of our first meetings with him. He was referring to the 24,000 tree saplings planted last summer as part of a 100-year experiment on biodiversity, fittingly called BiodiversiTree.

Click to continue »

Posted in Ecology, From the Field, Interns, Land Use, SERC Sites and Scenes | Comments Off on Intern Logs: A Bloody Welcome

Wednesday, June 11th, 2014

by Kristen Minogue

Swamp Rose Mallow with blades of Schoenoplectus americanus, a sedge in Drake’s marsh experiment. (SERC)

Plants are among the world’s best carbon sinks, but there’s a side to the plant-CO2 love affair that’s rarely discussed. When carbon dioxide rises, plants cling to it more, releasing less back into the air—and until recently, scientists couldn’t figure out why. With a new paper published June 11 in Global Change Biology, ecologist Bert Drake believes he finally has the answer.

The process is called respiration, and it’s one of the most overlooked parts of the carbon cycle. Unlike photosynthesis, in which plants absorb carbon dioxide and release oxygen, respiration reverses it. And plants respire constantly. Much of the CO2 plants take from the atmosphere for photosynthesis finds its way back via respiration from plants and soil. Which leaves a major question: How much carbon can the world’s ecosystems store as CO2 rises and climate changes?

Click to continue »

Posted in Climate Change, Ecology, Publications, SERC Sites and Scenes | Comments Off on The Strange, Controversial Way Plants Trap CO2