by Kristen Minogue

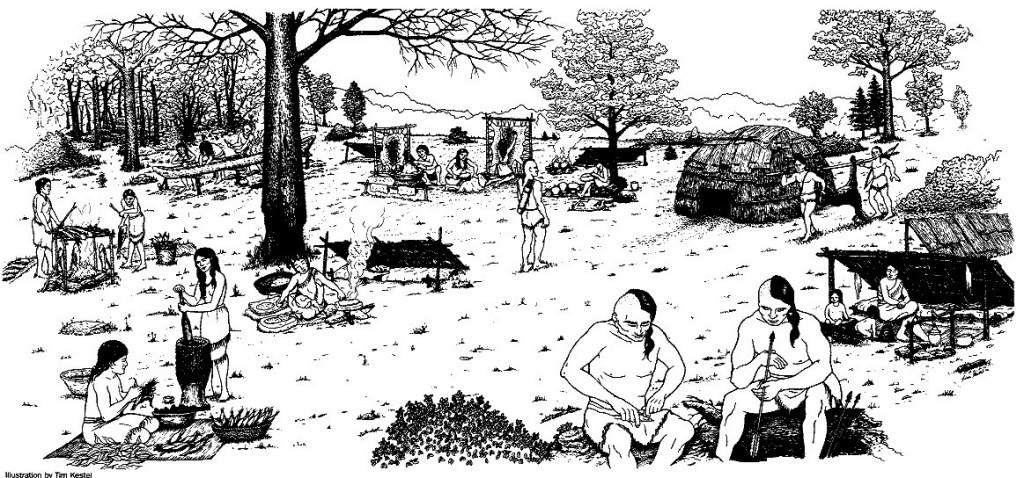

Piscataway Indians lived on the Rhode River up to colonial times, though anthropologists believe they used the land for temporary campsites, not permanent settlements.

For more than 10,000 years, Native Americans hunted and fished in the Chesapeake. Broken pottery, village sites, burial grounds and other artifacts bear witness to their near-continuous presence around the Bay. But one type of artifact—ancient trash piles called shell middens—hasn’t received as much attention. And these tell another important story.