by Kristen Minogue

SERC research associate and Portuguese native João Canning-Clode. (Valentyna Chan)

Since he began surveying the waters of Madeira two years ago, João Canning-Clode has discovered a new invasive species almost every month. The archipelago off the coast of Portugal is a hot spot for biodiversity, especially for bryozoans – “moss animals” that often cover rocks, piers and other artificial substrates. But he didn’t anticipate finding a completely new species, let alone two.

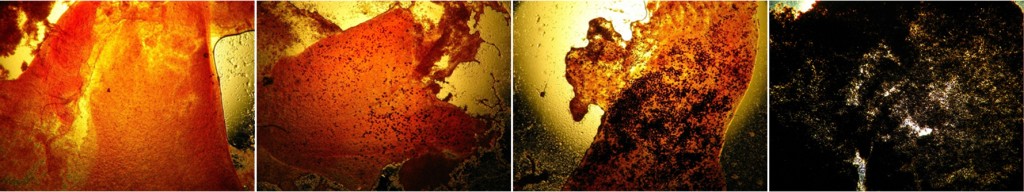

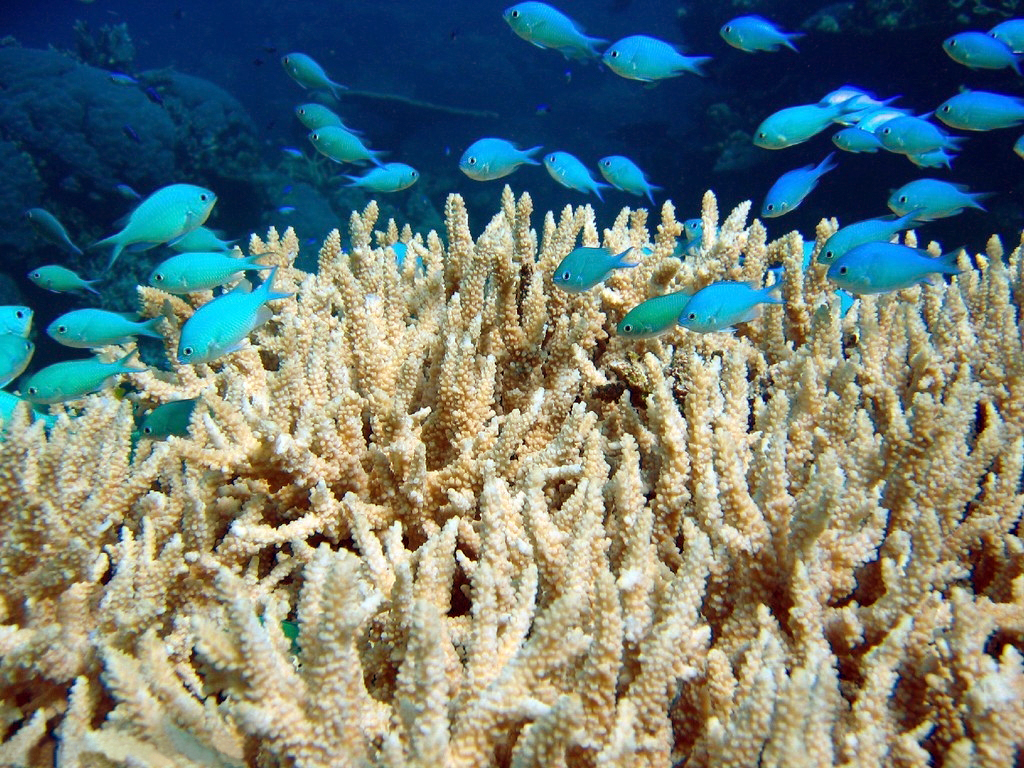

Bryozoans are easy to mistake for plants or corals from a distance. Some resemble moss as they form encrusting colonies on underwater rocks. Others form branching, bush-like colonies that look more like algae or corals. Up close, though, a single colony can contain millions of individual, tube-shaped zooids. The zooids support each other. But break a piece off, and a single zooid can start a new colony of its own.

The team named the new species Favosipora purpurea (for its pinkish-purple color) and Rhynchozoon papuliferum (for its special triangular-shaped zooids). In this Q&A, Canning-Clode, a research associate with the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, details the dual discovery published this month.

Click to continue »