by Cora Johnston

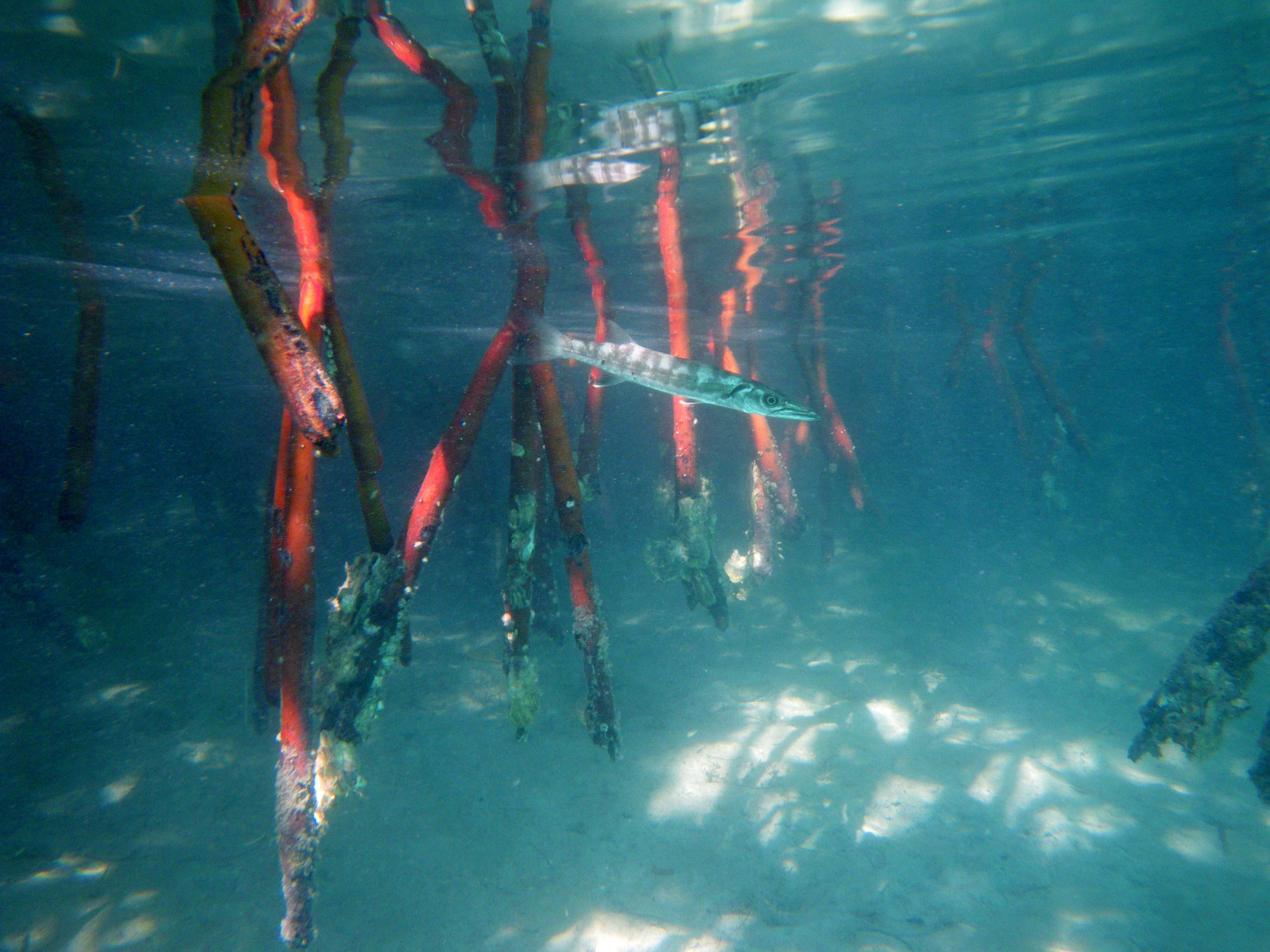

The waters beneath mangroves are teeming with marine life, in part due to the refuge provided by the tangled complexity of their underwater roots. (Cora Johnston)

From salty branches to mucky roots, mangroves are teeming with life. Although many people recognize mangroves as spindly trees emerging right out of the water, it is under the water’s surface that mangroves really come alive for a marine ecologist like me. (That is also where you start to appreciate red mangroves’ apt name.)

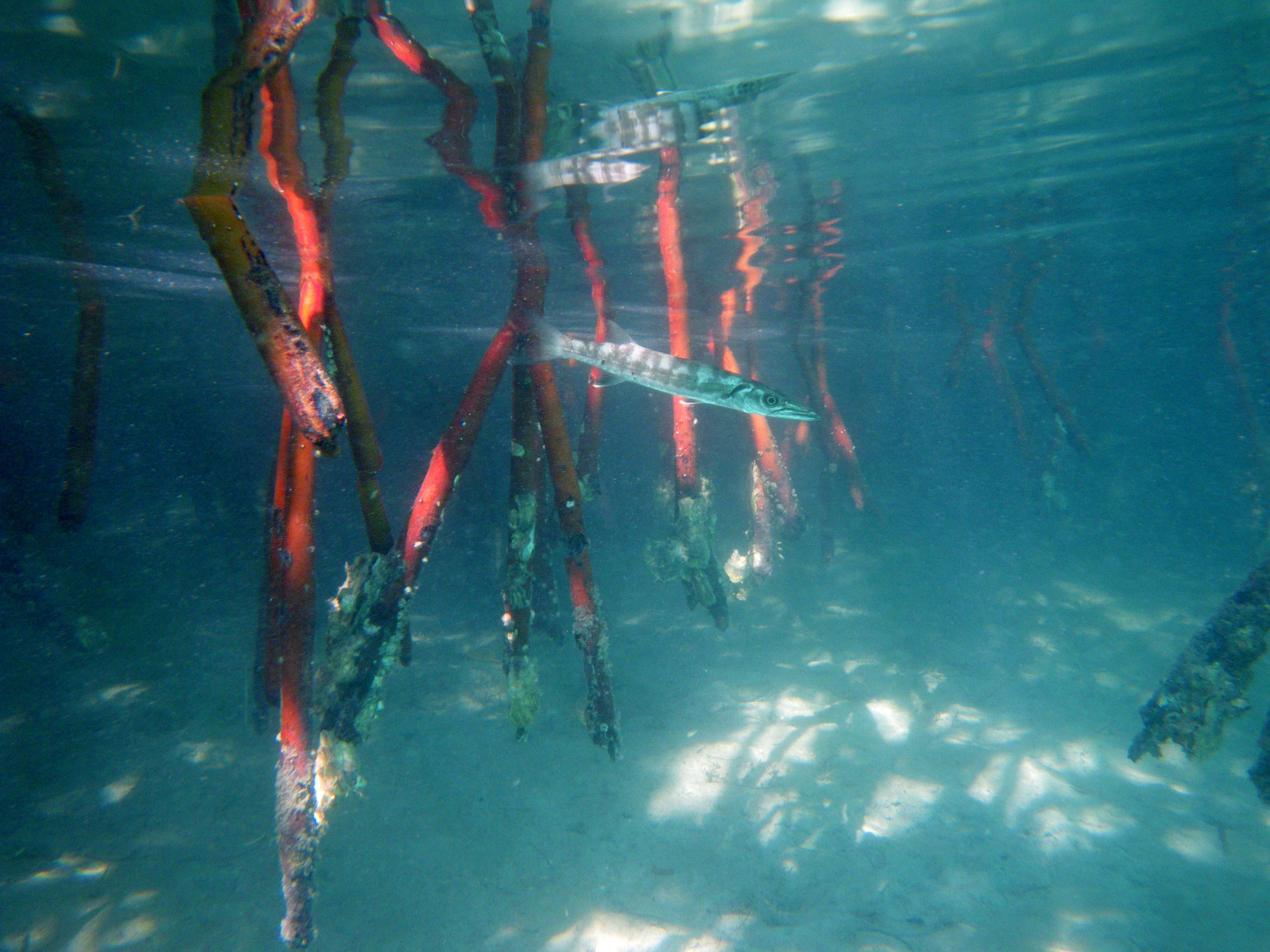

Mangrove roots, both dangling from above (prop roots) and growing up from the sand (pneumatophores), not only mine for nutrients and allow for oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange for the plant; they also provide apparently crucial food and refuge for a stunning array of marine species. Fish, worms, crabs, shrimp, barnacles, and many other organisms take shelter among the roots – gluing right to the wood, hiding in crevices, and peering out through the maze. In such harsh intertidal conditions, where waves break, salt builds up, and the sun beats down, the shade and nooks formed by mangroves may be the key to survival for juvenile fish and crustaceans that will someday populate coral reefs and fishing hotspots farther offshore.

Over the coming months, I will be investigating how and why young fish and crustaceans use mangroves and marshes. By understanding the refuge provided by these very different coastal plants, I hope to better understand how the northward march of mangroves will influence the survival, abundance, and composition of marine species utilizing these now changing coastal nurseries.

Juvenile fish and crustaceans find safety in red mangrove roots during the early, vulnerable stages of their life. This young barracuda may be looking for a snack while hiding from larger predators. (Cora Johnston)

Even mangrove tree crabs that spend most of their time foraging in the canopy climb down to the safety of the mangrove roots to shed their old exoskeletons and harden their new ones. (Cora Johnston)

-Cora Johnston is a PhD student at the University of Maryland. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Number 1065098. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

More stories from the mangroves >>