by Katrina Lohan

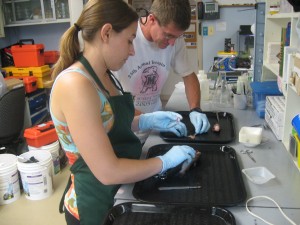

Seaside Hall at the VIMS Eastern Shore Laboratory, where Katrina Lohan and Kristy Hill spent most of their time taking samples from bivalves. (Katrina Lohan)

The end of our field season (if you call half a year a field “season”) is coming to an end as we now head for our sampling location in the Chesapeake Bay. Our northernmost sampling location is Wachapreague, Va., located on the Delmarva Peninsula and home of the Eastern Shore Laboratory (ESL) of the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS).

Kristy and I are both alumnae of the College of William and Mary and conducted our graduate research at VIMS. For my Ph.D., all of my fieldwork was conducted at the ESL, so returning as a postdoc, working on a different disease system, is a little surreal for me. It has been nice to catch up with the folks at this lab and see the new buildings, which were still in preparation when I graduated. How time flies!

Before venturing out on this particular trip, we contacted our collaborator Ryan Carnegie of the Shellfish Pathology Lab at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science to get some suggestions about sampling location. He suggested sampling oyster reefs at Mockhorn Channel just off Oyster, Va., as they had historical data from that area. The folks at the ESL knew just where to take us and we headed out on Tuesday to collect.

In previous locations we aimed to collect three oyster species. However, there is only one oyster in the Chesapeake Bay: Crassostrea virginica, the eastern oyster. So we decided to collect other bivalves: the ribbed mussel (Geukensia demissa) and the hard clam (Mercenaria mercenaria).

Our boat captain, Edward Smith, suggested that we split up so that we could complete the collection prior to the tide coming in. I ended up on the high marsh searching for mussels, which was super muddy and, consequently, lots of fun! It was beautiful weather and just windy enough that the bugs stayed away. Once all the mussels and oysters were collected, we all headed to a mud flat to rake for clams. I have to admit that I am horrible at finding clams. While Edward found more than 30 clams, I found three….Good thing that others were better than me or we would never have found enough. Then it was back to the lab to figure out how to shuck them all!