by Katrina Lohan

Sherry Reed (in pink) and Kristina Hill pick through clumps of oysters removed from the seawall at the Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute. (Katrina Lohan)

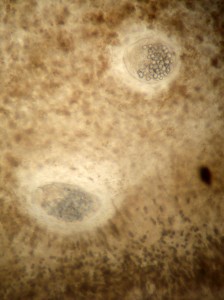

It was my job to hold the boat against the seawall while Kristy and Sherry hammered oysters off the wall. I also kept track as they called out numbers of Ostrea sp.—we didn’t bother counting Crassostrea virginica because they were everywhere! Unfortunately for us, there were no Isognomon sp. along the wall, which we all found odd given that this habitat was so similar to the seawall we had previously sampled, where we found that species.

After about an hour of sampling, we were all wishing for the breeze! Without that breeze, the sun intensity felt more brutal and it was stiflingly hot. Once we had enough C. virginica and Ostrea sp. we drove around to a few other spots within that inlet to see if the Isognomon sp. were more localized, but no luck. I wanted another sediment sample from this site, but it was too deep along the wall, so Sherry found a spot in the mangroves that wasn’t too dense. I hopped out of the boat and took my sediment and water samples. I started looking for Isognomon sp. on the mangrove branches, but only found a handful… We had one last look on the rocks on our way out of the inlet, but no luck there either. Bummer! Well, two out of three species isn’t too bad!