Biologists Detect Longest Transoceanic Rafting Voyage for Coastal Species

by Kristen Minogue

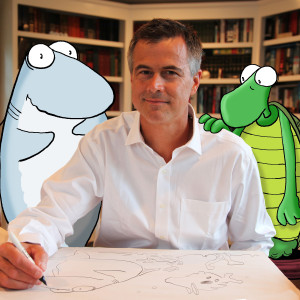

A Japanese tsunami vessel washed ashore in Oregon, coated in gooseneck barnacles. In a new study, scientists detected 289 species that rafted from Japan to the U.S. on tsunami debris, and they suspect many more were undetected. (Credit: John Chapman)

The 2011 Japanese tsunami set the stage for something unprecedented. For the first time in recorded history, scientists have detected entire communities of coastal species crossing the ocean by floating on makeshift rafts. Nearly 300 species have appeared on the shores of Hawaii and the U.S. West Coast attached to tsunami debris, marine biologists from the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, Williams College and other institutions reported in the journal Science on Thursday.

The tsunami formed March 11, 2011, triggered by an earthquake of 9.0 moment magnitude that struck Japan the same day. When it reached the shore, the tsunami towered 125 feet (38.38 meters) over Japan’s Tōhoku coast and swept millions of objects out to sea, from small pieces of plastic to fishing boats and docks. These kinds of objects, scientists said, helped the species attached to them complete the transoceanic journey.

“I didn’t think that most of these coastal organisms could survive at sea for long periods of time,” said Greg Ruiz, a co-author and marine biologist at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. “But in many ways they just haven’t had much opportunity in the past. Now, plastic can combine with tsunami and storm events to create that opportunity on a large scale.”