by Heather Soulen

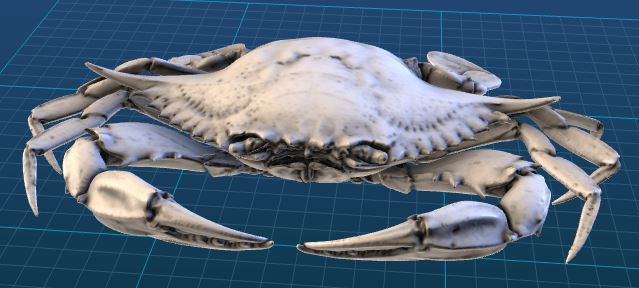

A Chesapeake Bay NOAA mullet skiff. Note the motor near the bow. (SERC)

With its motor located near the bow (front) of the boat, the modern-day mullet skiff could have been a character in Lewis Carroll’s novel “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.” Similar to the unpunctual rabbit, vanishing cat and hookah smoking caterpillar, it seems illogical…or does it?

Commercial mullet fishing in 1955. (Monts de Oca, C. Morris courtesy of State Archives of Florida)

In the early 1900s, the mullet skiff was originally designed for use in the commercial mullet fishery of the south. Popular for its simple construction, flat-bottom dory style hull with vee entry, and rounded stern (back) design, the mullet skiff was ideal for operating in shallow waters while carrying heavy loads of fish. However, during Prohibition, entrepreneurs souped up their mullet skiffs with straight-8 engines (precursor V8s) to run rum from the Bahamas and Cuba to the states. Since then, many mullet skiffs have undergone less scandalous modifications and have evolved to have an outboard motor in a well near the bow.

Why place a motor here? For three important reasons: 1) It places the motor higher in the water for maneuvering in shallow water, 2) it leaves the stern (back) open to work a net, and 3) it eliminates the risk of net entanglement in the propeller. So, with “the wrong end in front,” the mullet skiff was the perfect choice for the near-shore predator study our field crew conducted this summer throughout the Chesapeake Bay.

Predators of the Not-So-Deep

Click to continue »