by Sara Richmond

Sarah Grady and other archaeology volunteers use this large wooden sieve to sift through soil in search of artifacts. (Photo: Sara Richmond)

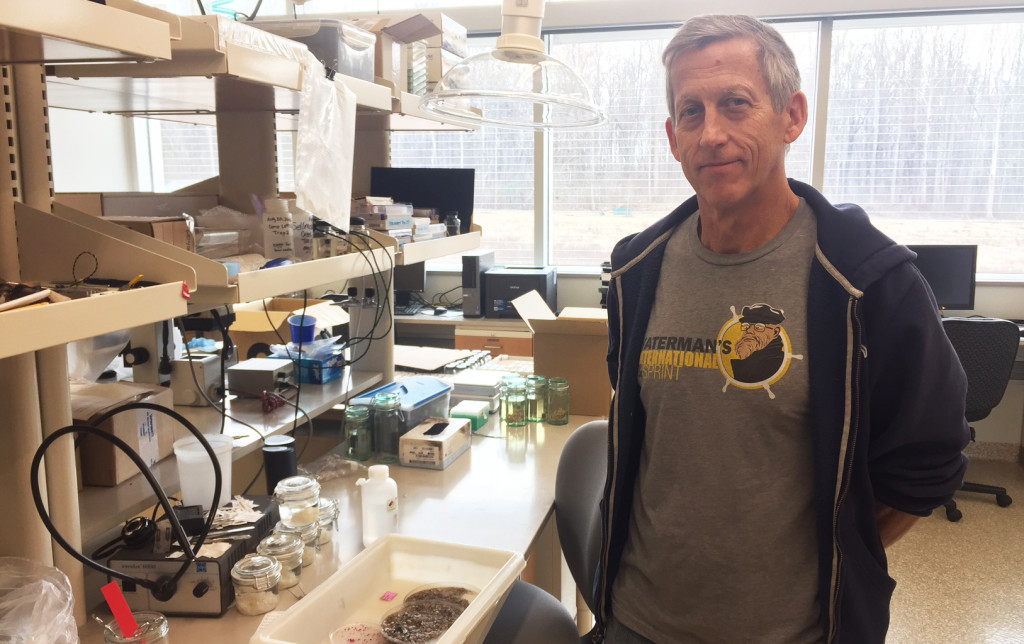

In 2012, Sarah Grady was waiting tables at the Old Stein Inn and deciding what to do with her new anthropology degree when a restaurant customer told her about the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center’s Archaeology Lab, located just a few miles from the restaurant. Soon after she became the lab’s second volunteer, working with volunteer lab director Jim Gibb to excavate plots and crunch data. Six and a half years later, Sarah is the lab’s assistant director. The year-round program has grown from just her and Jim to a group of roughly a dozen citizen scientist volunteers who gather every Wednesday to dig and learn about each other’s projects.

The Archaeology Lab is the only all-volunteer lab at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC). Currently the lab hosts 16 ongoing projects, all of which citizen science volunteers have undertaken on their own.

“We guide them,” says Sarah, “but most of them have taken the research into their own hands and are even making appointments with other scientists to discuss.” Click to continue »