by Kristen Minogue

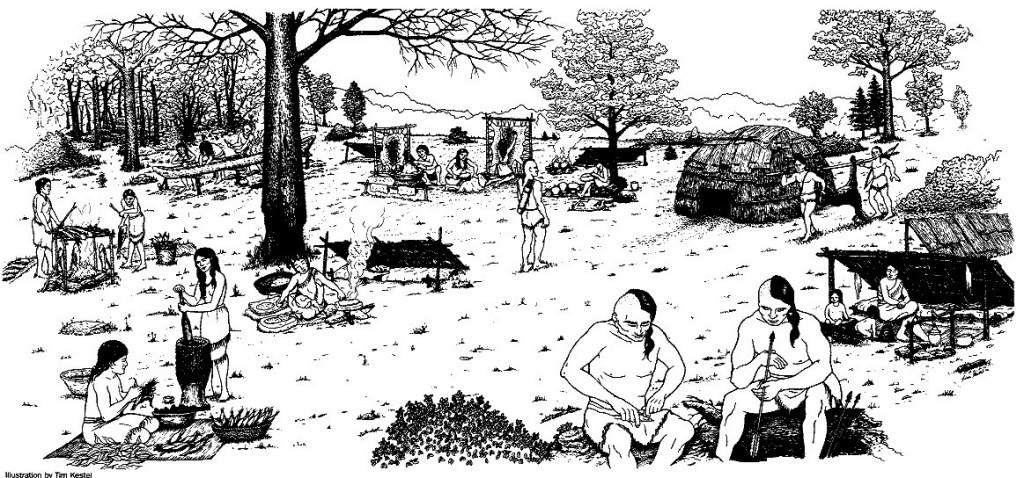

Piscataway Indians lived on the Rhode River up to colonial times, though anthropologists believe they used the land for temporary campsites, not permanent settlements.

For more than 10,000 years, Native Americans hunted and fished in the Chesapeake. Broken pottery, village sites, burial grounds and other artifacts bear witness to their near-continuous presence around the Bay. But one type of artifact—ancient trash piles called shell middens—hasn’t received as much attention. And these tell another important story.

Shell middens consist of thrown-out oyster shells and other refuse from feasts of long ago. That kind of trash is valuable for scientists like Torben Rick, an anthropologist at the National Museum of Natural History. Ancient refuse piles not only reveal what Native Americans ate and how they used the land. Scientists can also date them using the carbon isotopes in the shells or charcoal deposited at the site.

The banks of the Rhode River in Maryland, headquarters of the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC), are littered with shell middens from up to 3,200 years in the past. As part of SERC’s archaeology program, Rick and a team of researchers from SERC and Natural History set out to date 31 middens here, with help from volunteer citizen scientists and Anne Arundel County researchers. They expected to uncover a narrative similar to the one told by other artifacts, a fairly unbroken record of communities passing through the area. But instead they found something far stranger: a gap of almost a millennium.

An open pit exposes an ancient shell midden from roughly 1250 B.C. Native Americans used middens as trash piles for oyster shells, animal bones and pottery. (Torben Rick/Smithsonian)

The oldest midden Rick’s team found dated back to 1250 B.C., a time known as the Early Woodland Period. Other shells on the same site show Native Americans continuing to use that midden until 800 B.C. Then the record cuts off. No other middens appear until 150 C.E., more than nine centuries later.

The missing nine centuries of oysters don’t jive with their other ideas about that time period, according to Rick. “It’s a time when we think populations were growing, so we probably should have sites that date to that interval. “

According to some records, there are sites that date to that time. In 1975 an anthropologist named Henry Wright used artifacts to date a few middens to between 500 B.C.E. and 200 C.E. But when Rick’s team went back to check the findings with more precise radiocarbon dating, three of the middens dated to 500 C.E. or later (one after Columbus)—meaning the artifacts Wright found probably came from somewhere else—and a fourth was under water.

However, there’s plenty of evidence that people were living on the river during the missing years. The gap falls in a Middle Woodland period known as the Popes Creek phase, and others have uncovered Popes Creek ceramics on SERC property. Then there’s the Adena burial ground, a large cemetery in the area from between 400 B.C.E. to 100 C.E. that defies anyone who claims the land was empty. All that considered, Rick said, “it was a bit surprising.”

With all the other signs of life (and death), why are there no oyster shells? There could be several reasons. Native Americans might not have been harvesting shellfish during those years, or they could have deposited them somewhere else. Alternatively, communities may have been more spread out at the beginning of the Middle Woodland, so middens would be fewer and far between. Then there’s always the possibility of a sampling error.

“It remains possible that we just missed it,” Rick said.But Rick believes another force may be at work. The land around Chesapeake Bay has been steadily sinking as sea level has risen during roughly the last 15,000 years, and climate change is only accelerating the pace of the flooding. It’s completely plausible that oyster middens from the missing years were simply eroded or washed under water.

It wouldn’t be the first time something like this has happened. “We’re seeing archaeological sites more and more eroding away or heavily threatened by marine erosion,” he said. “So the project we did dating these sites is one step to try to race against that rising tide.”

Lost cultural relics are just one potential casualty of sea-level rise and climate change. If Rick’s theory is correct, the 950-year gap may be telling us more about the present—and the future—than about the past.

Learn more: How Native American compost is shaping forests today

The study was published in the September/October issue of Geoarchaeology. The online abstract is available here.