New study finds antibiotics from poultry farms can lead to drug-resistant bacteria in the water

by Kristen Minogue

Chickens stand in a Pennsylvania poultry barn. Crowded conditions in poultry barns increase the danger of a disease spreading through the flock, leading many poultry farmers to rely on antibiotics. (Credit: Steve Droter/Chesapeake Bay Program. Creative Commons License)

90 tons. That’s how much chicken manure—mixed with feathers, uneaten feed and leftover bedding—a Maryland poultry farmer scrapes out of a single barn each year.

Manure is just one of many issues poultry farmers on the Delmarva peninsula have to wrestle with. Poultry farming isn’t an easy industry, for the chickens or the farmers. To get started, a farmer generally needs to borrow hundreds of thousands of dollars to build a poultry barn to house roughly 45,000 birds. Companies like Purdue and Tyson supply the chicks, and pay the farmers based on how many pounds the flock puts on. To have any chance of making a profit, there’s enormous pressure to grow broiler chickens as fat and as fast as possible. A typical poultry barn can go through five to seven flocks a year. After each flock moves out, the farmers are left to deal with the muck.

“The folks that grow the chickens, it’s a really tough job that they do and hard to make a buck at it,” said Tom Jordan, an ecologist with the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center who specializes in how farming impacts Chesapeake Bay.

Another thing that’s hiding in the chicken manure? E. coli bacteria. Some of these E. coli don’t cause disease. But others can inflict both chickens and people with diarrhea and other unsavory side effects, like urinary tract infections.

Some E. coli bacteria have become resistant to our antibiotics. This May, scientists reported that because chicken manure fertilizes farms throughout the Chesapeake, that antibiotic resistance can also spread in the water. Besides the already-prevalent problem of nutrient pollution, this could put swimmers and boaters who use the water for recreation at further risk.

“Right now, sometimes the poultry barns get cleaned and they immediately apply it on land, so it’s just fresh waste going directly on our land,” said Jay Graham, lead author of the new study and a public health researcher with the University of California, Berkeley. “So if it rains, then all that ends up in our waterways.”

Bacteria wars

Jay Graham (left) and Tom Jordan sample a stream for E. coli bacteria, nitrogen and phosphorus. (Credit: Kishana Taylor)

Antibiotics have a long history in the meat industry. Though the U.S. government has largely banned using antibiotics as growth boosters, farmers still rely on them to fight illness because industrialized poultry barns are so crowded.

“A chicken in one of these operations will have less than one square foot to basically move around,” Graham said. “They’re really packed in there. They’re basically standing over their own fecal waste.”

For farmers, the cramped space creates a constant fear that avian flu or another disease could decimate the flock. Antibiotics are, for now, a makeshift solution. But in typical arms-race fashion, bacteria have evolved to resist our drugs. And when chickens receive the same antibiotics as people, the public health threat is difficult to brush aside.

Tom Jordan, head of SERC’s Nutrient Cycles Lab, studies how pollution from nutrients and other chemicals flows through the watershed and reaches the Bay. (Credit: Jay Graham)

In the new study, Jordan and Graham—then at George Washington University—teamed up to find out whether antibiotic-resistant bacteria from poultry manure could bleed into the environment. They sampled for E. coli bacteria in 15 streams in the Chesapeake Bay region. Each stream had roughly the same type of surroundings. The only major difference was the number of poultry barns in each stream’s watershed, which ranged from zero to 80.

Back in the lab, the team tested the stream E. coli for resistance to various antibiotics. Roughly one-third were able to resist at least one of the drugs they tested. Only one kind of antibiotic resistance showed a clear link with the poultry barns, though: resistance to cephalosporins.

Cephalosporins are a group of common human antibiotics that are especially vital for people allergic to penicillin. About 14% of the E. coli they tested showed cephalosporin resistance.

“We really do not want to see cephalosporin resistance in E. coli,” Graham said. “It’s worse than, let’s say, tetracycline resistance. Because we’ve kind of already lost tetracycline in terms of its effectiveness as a drug.”

Social distancing with chickens?

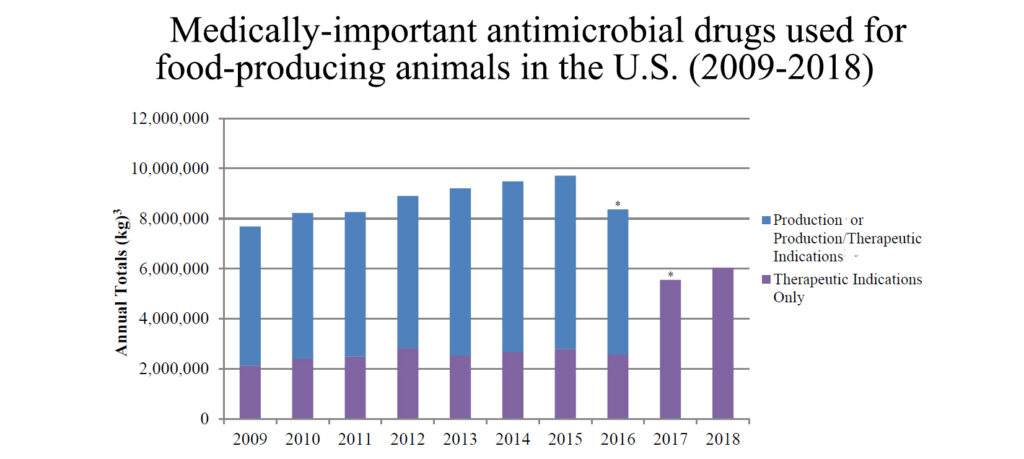

The U.S. Food & Drug Administration has already taken notice. In 2012 it began phasing out “medically important antimicrobials” for many animal uses, including boosting growth. Graham and Jordan took their E. coli samples in 2014, when antibiotic use was near its peak for the decade. Since then, the Food & Drug Administration has stepped up regulations even further. Today, almost all antibiotics for animals require a prescription or supervision from a vet instead of a simple over-the-counter purchase.

In the past decade, antimicrobial drug use on food animals peaked in 2015. Giving animals these drugs for growth (shown in blue) dropped to zero in 2017, after the full implementation of FDA rule GFI #213 that phased out that use. (Source: U.S. Food & Drug Administration)

Farmers may use antibiotics to treat animals that are actually sick. However, that doesn’t solve the root of the problem—the overcrowding that makes chickens so vulnerable to disease in the first place.

“It’s almost like you need social distancing with chickens,” Jordan said. Still, he acknowledged, the industry has largely forced poultry farmers to put efficiency above all else. Concentrating all their production in one area enables the farmers to keep costs down and stay in business.

“That’s a hard thing to get away from,” he said. “People go to the grocery store, they’re usually going to get the cheaper meat if it’s good and wholesome for them and it’s a few cents less.”

Graham would like to see more chicken manure treated to kill bacteria before it gets shipped off as farm fertilizer. Some farms are already doing this, but there are no standardized requirements. Graham has another even larger dream: a day when big companies like Tyson and Purdue take charge of the waste themselves.

“It’s become a burden to the farmer,” he said. “And what some farmers end up doing is overapplying the waste to the land because they don’t have the land, they don’t have the money, to distribute the waste over several watersheds.”

Some Maryland legislators took a stab at the idea in 2016, with a bill called the Poultry Litter Management Act. However, the bill never became law. Today, farmers are still dealing with the muck on their own.

For now, Graham and Jordan’s study reveals that antibiotic resistance can travel further than we thought. Finding a way to cut the need for antibiotics in farming, and not simply their use, may ultimately offer the best path forward.

“Antibiotics are this shared resource, and we want to protect them to the greatest extent possible,” Graham said.