by Kristen Minogue

On the western shore of Chesapeake Bay, less than a mile from the Rhode River, there is an old red house on an abandoned farm. Once, in the 18th century, it belonged to a thriving plantation. The hilled rows of tobacco have vanished, along with the field hands, tenant farmers and generations of enslaved Africans and African Americans who planted them. But the scars on the landscape remain. The surrounding earth carries traces of how each of its inhabitants have used it, or abused it.

The house’s first inhabitants in the early 1700s called it Woodlawn. Today it is known simply as the Homestead House. The building and its surrounding farmland now sit within the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. Instead of enslaved laborers and field hands, teams of volunteers are overturning the soil in search of clues about its past.

Archaeologist Jim Gibb began the excavation at SERC earlier in August. His volunteers come for a single afternoon, or several weeks. He isn’t terribly picky about long-term commitments. Gibb welcomes anyone who can handle a shovel and is at least ten years old (and even that rule is flexible). Under his guidance, they are piecing together the story of one household’s legacy on the land.

The team made one of their biggest discoveries just a few weeks into the project, when they uncovered a brick foundation sprinkled with household artifacts. One possibility is that it was a storage shed. Another, that it was someone’s home.

“If someone was living in that in the early 19th century, and we know where the owners were living, then we do the math,” Gibb said. “They have to be labor. And at that point, probably slave labor.”

One Family, Two Centuries

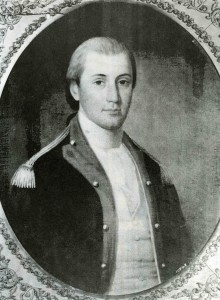

General Jonathan Sellman (1753-1810) lived in Woodlawn his entire life, except during the Revolutionary War, when he served in the Continental Army. He was at Valley Forge during the winter of 1777-78, and General Washington later gave him a sword in recognition of “courage and gallant conduct.” (Portrait by John Beale Bordley, courtesy of Sally Sellman and family)

The story of the Homestead House is, at its core, the story of a family. It is the story of the Sellman family, who built and lived in it for almost two hundred years. Records are hard to come by, but existing ones indicate that around the year 1658, a boy named John Sellman—about twelve or thirteen years old at the time—arrived in Maryland from England as an indentured servant. Like most indentured servants, he worked for a single household for ten or twelve years. When his term of service ended, his former employers released him with two warrants worth 50 acres of land a piece. For the remaining forty years of his life, John Sellman worked his way up the socioeconomic ladder until he had a plantation and indentured servants of his own.

It was John Sellman’s son, William, who built the Homestead House. In 1729 he and his wife, Ann, moved to a 360-acre plantation then known as “Shaw’s Folly.” William reportedly had the house constructed in 1735, where it still stands today. The family weathered two major wars inside its walls. General Jonathan Sellman (then a captain) fought with the Continental Army at Valley Forge during the harsh winter of 1777-78. His younger brother, Dr. John Sellman, served as a gunner’s mate in the 1st Maryland Artillery.

By the time the Civil War erupted, the family had scattered across the country. The Ohio Sellmans fought under the Union flag, while Maryland Sellmans tended to side with the Confederacy. But the abolishment of slavery did not drastically alter life on the Sellman plantation. Formerly enslaved laborers were free, but many remained as hired help, according to descendant Richard Donavin, who remembers stories his grandmother told. This could be partly because Maryland wasn’t in the deep South.

“The farther north you went, the closer you were to the abolition line,” Donavin said. The uneasiness of having abolitionist neighbors sometimes meant slightly better conditions for those enslaved, even before emancipation. Donavin’s grandmother, Ellen Parran Sellman, belonged to the last generation of Sellmans that lived in the Homestead House. After 1915 the family sold it, and it passed to the enthusiastic tree collector Yvone Kirkpatrick-Howat.

However, like most historical tales, there are gaps in the telling. One of the biggest mysteries—for Gibb at least—is its real age. The house has three sections, all built in different centuries: a passive-solar wing added in 1979, a Greek-revival style wing built in 1841 and, directly between them, a brick section enclosing what was once the central kitchen. One of the bricks has the year 1735 etched onto it. But Gibb doubts this is valid. While craftsman of the period often signed their work, they usually did it in more out-of-the-way places. A crude carving right by the doorway could have come from anyone, at any time.

“I don’t think that it has anything to do with when that building was constructed,” Gibb said. “Somebody put that on much later, possibly in the late 19th, early 20th century. But it’s just a hypothesis.”

Then there is the baffling stone foundation—a foundation that, while technically beneath the house, doesn’t seem to be supporting anything. Gibb speculates that it may have supported an older house that burned down, perhaps in the 18th century.

Legacy on the Land

Volunteer Dwante Graf-Jones dusts soil off bricks that may once have made up the home of an enslaved laborer.

Some of the greatest revelations are lurking outside the house, in the earth surrounding it. For more than 250 years, the home’s residents felled trees, tilled the soil, covered it with foreign plants and dumped their trash onto it. All those actions left marks on the landscape that persist centuries later. Though many lie buried beneath layers of dirt, some are staring plainly from the surface.

Example: The gently rolling emerald slopes stretching almost a mile behind the house? Not natural. The scenic hills are the product of excessive erosion, just one side effect of poor farming practices that were the modus operandi in 19th-century America. Grains of coal in the soil also have a story to tell. With acres of trees on the property, Gibb says there would be no reason for the Homestead House inhabitants to burn coal—unless, of course, they had already cut down all the trees.

But it would be a mistake to think all human activity on the property was destructive. The solar wing tacked on in 1979, while a far cry from today’s green standards, was a major leap forward in an era when the idea of clean energy was just in its infancy. And the early 20th-century Sellmans, like many Americans, did not rush to embrace the horseless carriage.

“The horse was something they had grown up with,” Donavin said. His great-aunt, Victoria Sellman, thought of their horses as part of the family and could not believe the automobile ever caught on. “Now this was being taken from them and being replaced by this unfeeling, dead, mechanical machine.”

Meanwhile, the collection of artifacts in Gibb’s trailer is growing. Animal bones, nails and fragments of ceramic dishware (most from the 19th century) are painting a rough picture of how the Sellmans—and the enslaved laborers and tenant farmers—lived on the property. Artificial terraces on the lawn recall the formal gardens of the aristocracy, a popular landscape that fell out of favor after the Revolutionary War. He’s even uncovered pottery shards from a Native American campsite made between A.D. 1200 and 1500.

There are more mysteries to unravel. Some will require Gibb to literally read the bones of the animals: Did the Sellmans kill mostly domestic creatures like pigs, or did they hunt wild deer? And if they went hunting, how many did they shoot? Did they focus on large bucks, or did they take fawns and does as well? He’s also looking at what they threw out–which means a fair amount of his work will involve going through the Sellman’s trash.

What Gibb and his volunteer crew uncover may not be the legacy William Sellman imagined leaving when he built the house 280 years ago. But the house itself will remain standing, as an architectural collage of three centuries, and a testament to the immense power humans have to shape the landscape.

Archaeological work on the Homestead House is continuing in the summer of 2014. No experience is required to join the excavation. To volunteer in the field or lab, contact Jim Gibb jamesggibb@verizon.net or SERC’s citizen science coordinator Alison Cawood at cawooda@si.edu.

Image of Jonathan Sellman portrait and history of the Sellman family taken from John Sellman of Maryland and Descendants by W. Marshall Sellman (1975).

This house belong to my grand mother Ellen Sellman Donavin. We have many records of historical signifigance, which I’m willing to share.

Please at the above email: Thankyou!

I am the great….Grandson of Jonathan Sellman. I was name after him by my Mother. I think the work you all are doing is fantastic, and the reason for me writing you is to ask your permission for me to be apart of the restoration. I am a hard worker and a lover of History. Please let me know. Thank You, Jonathan Taylor

Jonathan Selllman was also my (many times) great grandfather. At some time I also hope to be able to help with the restoration work.

William and Ann Sellman were my…great grandparents. Wonderful to see the work you are doing…would love to help if I lived closer! I hope to be able to visit someday!

My son and I have volunteered, and are really enjoying the experience of hands on history.

I am also a great Grandson of Jonathan Sellman. I was truly humbled and encouraged to learn of the great history of my family and the amazing figures they were. I am honored to have come from such amazing and influential people. My wife Joy and I have been to my great Grand Fathers home a few times and we plan on bringing our future children here so that they will know where we come from and most importantly, who we are!

We have traced the history of the Sellman family back to the 16th century in East Sussex. Contact ladykingston@btinternet if you would like any details.

On September 2, 2014, my 81 year old mother, Callie Sellman McMurry the 7th great granddaughter of William Sellman and Anne Sellman, my daughter, Rachel Graves Jones, 9th great granddaughtet of William and Anne Sellman and me,8th great granddaughter of William and Anne Sellman, visited Woodlawn, the Homestead House. It was a wonderful experience. Thank you for preserving the area. We were hoping to have taken part in the dig, but there was no activity the day we were there.

I am not sure that it is entirely just to hold humanity accountable

On September 2, 2014, my 81 year old mother, Callie Sellman McMurry the 7th great granddaughter of William Sellman and Anne Sellman, my daughter, Rachel Graves Jones, 9th great granddaughtet of William and Anne Sellman and me,8th great granddaughter of William and Anne Sellman, visited Woodlawn, the Homestead House. It was a wonderful experience. Thank you for preserving the area. We were hoping to have taken part in the dig, but there was no activity the day we were there.

Wow. I too am a many times great grandson, in fact I was named for the man. I have his picture in my living room. I didn’t realize the homestead was there. I need to come down and check this place out. It looks amazing. Thanks for all the history and information.

The archeological work at Woodlawn sounds like a great project with incredible community involvement. I am also a great-grandson (9 generations back) of William and Ann Sellman and hope to bring my family to help with this.

I’m also a descendant of John Sellman, but also of William Sellman, one of his (6) children. William had (8) children, I believe. Don’t seem to have been any infant deaths in either generation, which seems atypical. I was aware of an existing house [Woodlawn/Homestead], but it was never named in anything I found, so didn’t know where to start looking other than Davidsonville, area. I did find, in a book at the Mormon Family Research Library, a copy of the complete will of John (Jonathan) Sellman, dated 1701, I believe. In it he bequeaths his two farms. Also, I’m pretty sure that his wife Elizabeth was the daughter of a French Huguenot, Benin Brasseurs. And that Benin was his master. My records indicate John worked for Benin for 15 years, and was free of his indentured status at the ripe age of 31 (which would indicate he started at the age of 16?). But he may have gotten a bonus: he married his [former] bosses’ (Benin) daughter, who was only 16 years old at that time. So it seems likely that John knew Elizabeth as a child and she knew him almost from her birth.