by Jaylene Lopez

You may have heard of invasive species like mitten crabs, emerald ash borers and zebra mussels that wreak havoc on the ecosystems they enter. But have you ever considered the invasive species that are invisible to the naked eye?

“There’s been a lot of research on the transport of larger organisms and the role of shipping,” said Katrina Lohan, head of the Coastal Disease Ecology Lab at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center and a coauthor of a recent paper about invasive parasites. “My interest in it, though, was thinking about how these organisms that are larger, that we can see, are also potentially transporting, transmitting or dispersing organisms that are smaller, that we can’t see.”

International shipping spreads many invasive species across the world. However, though there is much less press and scientific research about parasites, they can spread the same way. Many scientists haven’t considered that parasites can spread through the ballast water in ships’ hulls. When a cargo ship reaches a new area, it discharges the ballast water it uses for stability into that new ecosystem. This ballast water can carry invasive species, including parasites.

Lohan’s paper concluded that ships are indeed carrying parasites across international waters, making them a possible source for marine disease outbreaks. Her team identified 105 parasitic families in the ballast water of ships they sampled. To truly understand how much of a threat this poses, the writers stressed the need for further research.

“Just because we found them in ballast water doesn’t mean that they survive in a new location,” said Lohan. It’s also unknown whether these parasites will infect nearby plants or animals.

One thing is for sure: Alive or not, loads of parasites are being moved around.

Landing parasites in deep water, literally.

How do we stop this spread? Slamming the brakes on global shipping is a non-starter. Besides the wrench this would throw in the global economy, this would raise several ethical questions about the prices of goods and who has access to them.

Shipping by cargo boat is a cheap and effective way to transport essential goods. If those who can afford more expensive modes of transport are the only ones with access to essentials, we’re going to have a humanitarian issue on our hands.

On the other hand, there have already been outbreaks of human diseases related to ballast water. For example, ballast water is to blame for a cholera pandemic in Brazil in the early ‘90s. To prevent outbreaks, the International Maritime Organization generated guidelines that require ships to move out into open seas to exchange their water instead of near the coasts, and to limit the amount of organisms in their ballast water.

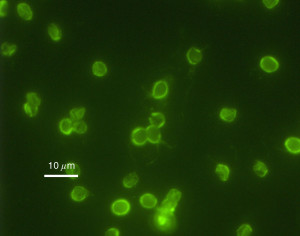

This ensures that fewer organisms will survive to reach coastal areas. However, the guidelines still ignore the vast diversity of parasites that don’t affect humans but can impact coastal food webs. “IMO Guidelines do not address organisms under 10 microns, which are most parasites, except for two indicator taxa, both of which are zoonotic bacteria,” said Lohan.

The next step is finding out if this can cause damage to local ecosystems. “Personally, what I’m more interested in seeing happen is generating the knowledge that this is an issue,” said Lohan. “So [that] it’s not on the radar of just the scientists who are studying these invasions, but also managers who are thinking about their role and then about how we better incorporate these into management strategies.”

And while most people can’t directly stop ballast water invasions, there’s at least one thing that you can do about invasive species you can’t see: Wash your shoes!

“If you went traipsing through mud somewhere, then get on an airplane and take those same shoes and don’t wash them somewhere else,” said Lohan, “there are invisible organisms in that mud that you are transporting with you.”

As always, to avoid invasive species getting into new ecosystems in general, never release your pets back into the wild. Try to find an animal shelter that will care for them.

Research Woes, and Research Whoa’s!

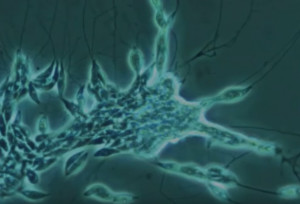

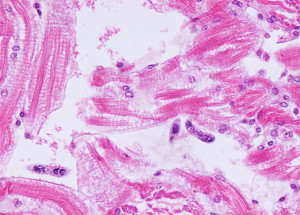

To conduct the research, Lohan and her team collected ballast water from 19 ships entering Virginia, Texas and Alaska. From the samples, they extracted ribosomal DNA from zooplankton and eukaryotes in the ballast water. They then divided them into three different size groups and analyzed them for parasite richness.

Parasites thrived abundantly in ships entering all three states. The researchers found a vast diversity of parasitic taxa that can infect multiple hosts, including fish and algae.

With every scientific study, there are questions and challenges. One challenge was how the team would present their data. Funding is always an issue in science, so the team had to generate the three datasets with slightly different techniques. This made it more difficult to figure out a legitimate way to combine the data for statistical comparisons.

“How do I pull this together to really show the broader diversity of parasites across these different types of samples that all make up the components of ballast water that we’re worried about?” said Lohan. Eventually, after going back and forth with her coauthors, they were able to tie together the different datasets.

For Lohan, the holistic picture her team managed to achieve was the most fulfilling part of the paper. Time and funding are limited, so tying these datasets together is a major achievement.

“Our ability to synthesize that across these different datasets in a meaningful way,” said Lohan, “made this paper more powerful because we could add in the different size classes and components… and that made it really exciting for me.”

This new, exciting research still leaves unanswered questions. How will this affect our ecosystems? Are the regulations in place enough to protect us from marine diseases? Until more research comes out, we’ll just have to wait and see.

Access the study by Lohan and her team, “International shipping as a potent vector for spreading marine parasites” in the journal Diversity and Distributions at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ddi.13592.

Read More:

Slime Nets and Other Parasites Unmasked, Thanks to DNA

Undersea Parasite Impregnates, Crabs, Male and Female

Q&A: Katrina Lohan, Marine Parasite Hunter