by Kristen Minogue, Regina Eisert and Olav Oftedal

Because they must learn to navigate under sea ice in just over a month, baby Weddell seals are born with near adult-sized brains. (Samuel Blanc)

When it comes to brain size, Homo sapiens generally get the most credit. But to find the baby mammals with the proportionally largest brains on the planet, Smithsonian scientists had to search in Antarctica. In a study published online in April, they found Weddell seal pups have the most developed brains at birth recorded for any mammal so far.

By the time they are born, baby Weddell seal brains have already reached 70 percent of their adult size. (The brain of a human infant is a mere 25 percent of its adult size.) But the researchers found this rapid development carries a hefty price tag.

The research team, consisting of Olav Oftedal (SERC), Charles Potter (NMNH) and led by Regina Eisert (SERC and the University of Canterbury, NZ), studied brain mass in 12 Weddell seals that died of natural causes in ice-covered McMurdo Sound, Antarctica. The seals studied included two adult females and 10 newborn pups zero to eight days old when they died. The scientists also measured intracranial volume of Weddell seal skulls from a collection held at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand.

The pups’ average brain mass measured 69 percent of the adults’ average brain mass. The figure reached an even 70 percent when they combined their work with data from earlier studies, an absolute record among newborn mammals studied to date.

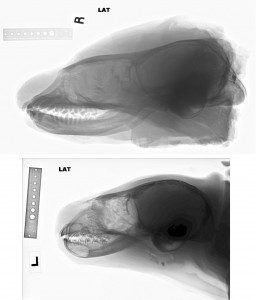

Radiographs of the skulls of an adult (top) and newborn Weddell seal. The cranium of the newborn is already close to adult size at birth. (Suzan Murray/National Zoological Park)

In general, offspring born at an advanced state of maturity will have proportionally large brains. This is especially true for marine mammals, which must cope with a challenging environment at birth, and some terrestrial ungulates such as zebras and wildebeest, whose calves run with the herd within hours of being born.

But why does the newborn Weddell seal need such a large brain? Marine mammals need extra processing capacity to orient themselves in a three-dimensional underwater environment, and tend to have larger brains than comparable terrestrial species. (Living in trees, another kind of 3D environment, is also associated with larger brain size).

As an added challenge, baby Weddell seals take up diving under the ice at less than three weeks old. Ice-diving is extremely dangerous for mammals, as they risk drowning if they cannot locate their exit in time. Most marine mammals will not dive under closed ice even as adults, with the exception of three species: the Baikal seal, the ringed seal and the Weddell seal.

And why are baby Weddell seals—which may be seen shivering from their icy swims at just a week old—in such a rush to brave the dark, freezing, and potentially lethal waters in the first place? It appears that they have no choice. Weddell seal mothers attend their pups for only 40 to 50 days. After that, the young are on their own. With such a small window of time, pups are under a lot of pressure to master the under-ice navigation skills they will need for the rest of their lives.

But such hyper-fast maturity comes with a cost. The brain is a metabolically expensive organ, requiring a constant supply of oxygen and glucose (blood sugar). Any interruption of the brain’s fuel supply may result in loss of consciousness, so keeping the brain going takes top priority. Other tissues may even be broken down to help supply glucose for the brain. The team estimated a newborn Weddell seal pup of 30 kg (65 lbs.) needs between 30 and 50 grams of glucose per day, with the brain taking roughly 28 grams.

Weddell seals sleeping on the ice. While nursing their young, Weddell seal mothers go through a fasting period and can sacrifice a great deal of body mass to sustain their pups. (Regina Eisert)

Ultimately it’s up to the mother to supply that glucose through her milk. In a second paper published in March, Eisert, Oftedal and collaborators from New Zealand reported that the amount of milk sugar supplied by seal mothers (39 grams per day) matches the offspring’s needs almost exactly. This came as a surprise: Until now, it had been assumed that the sugar content of milks of seals and other marine mammals was negligible.

But this again carries a price. Lactating Weddell seal mothers have one of the highest rates of mass loss of any marine mammal, sacrificing their own body tissues to make milk for their large-brained offspring.