by Philip Kiefer

There’s a war of attrition playing out on the coastlines of the San Francisco Bay that is in a ponderous class of its own. A tiny snail, called a rough periwinkle (Littorina saxatilis), might be pushing its native counterpart, the checkered periwinkle (Littorina scutulata), from the beaches it once called home. But no one is quite sure why, or even how quickly it’s spreading.

Adrielle Cailipan, a recent graduate of San Francisco State University, is spending her summer internship in the world of periwinkles with the West Coast Lab of the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC). She’s working not only to document the spread of the rough periwinkle, but also to understand what makes the invader so successful.

The rough periwinkle is relatively new to the Bay. It was first seen in 1993 somewhere to the south of Oakland, where it was probably introduced in connection with baitworms imported from Maine for fishing. Since then, SERC scientists have watched it creep northward from beach to beach, slowly displacing the natives. Once established, the rough periwinkle isn’t likely to go anywhere. On the East Coast, one survey found there could be as many as 100,000 snails per square meter.

To a casual observer, the invasive rough periwinkle and the native checkered periwinkle look almost identical. The interloper is slightly rougher, slightly more angular. They both live on rocky beaches in between the high and low tide lines, grazing on the thin film of algae that slicks the rocks. In spite of their similarities, though, Cailipan says that they make bad roommates.

“We see only one kind or the other,” she says. If rough periwinkles have colonized a beach, there just aren’t any native snails to be found, and vice-versa. “We don’t know for sure if they’re competing, but it sure looks like it.”

It seems that rough periwinkles are displacing the checkered ones, but it’s unclear why the two snails can’t coexist. Cailipan wants to understand the rules of the game: Are the invaders mowing down too much algae? Multiplying too quickly? Or is there a subtle environmental difference between the beaches that we haven’t noticed? Figuring out the game means inventing experiments and tools to test the snails, but that’s a task Cailipan is up for—she loves the engineering that goes into scientific research.

Minor League Eating

To compare the eating habits of the two snails, she’s devised a creative solution: an algae-eating contest.

The experiment begins by dropping a PVC structure, covered in algae-friendly slides, off the SERC docks. Cailipan could grow the algae in the lab, but she wants to mimic the natural composition of algae in the waters of the Bay, and algae turn out to be incredibly finicky about growing conditions.

After a few days in the water, the structure is coated in ooze. With slimy algae-slides in hand, Cailipan can now release the hungry snails kept in buckets around the lab. But measuring a snail’s food intake has been a challenge on its own. A mouthful of algae doesn’t weigh much, and counting individual plants takes hours. Fortunately, the snails leave a shiny clean path behind them as they munch, and Cailipan can then use a machine-learning algorithm to estimate the total intake.

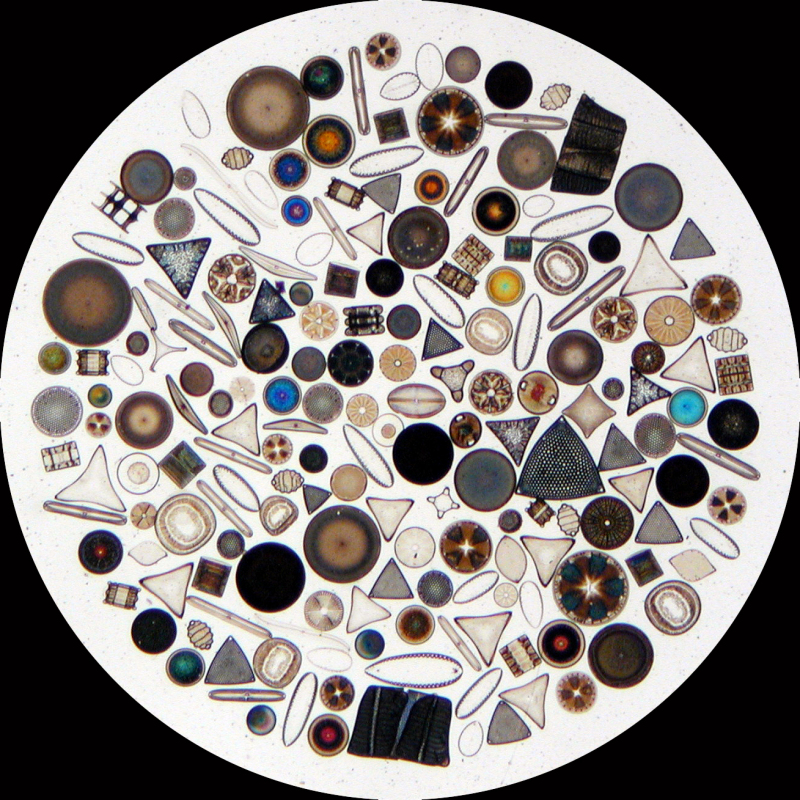

The eating contest idea came to Cailipan as part of her interest in algae. She loves the algae almost as much as the snails do. As an undergraduate, she studied the process of engineering algae for sustainable biofuel, partly because it was a way to do good with her scientific background, and partly because she finds the microscopic plants mysterious. Looking at a poster of single-celled algae, scattered like a handful of gemstones, she exclaimed, “Look at how beautiful these are! See, this is what I want to study.”

A collection of single-celled algae, called diatoms. (Wipeter)

If the rough periwinkles are in fact out-eating the checkered snails, Cailipan will have a much better sense of why they’re able to gain traction in an unfamiliar ecosystem.

But that’s likely not the whole story. There are lots of algae out there, so it’s likely that the snails are competing on other playing fields as well. Perhaps, she says, the rough periwinkle can tolerate heat or fresh water better, and therefore it can take over spaces with more stressful environmental conditions.

“Nobody’s really done in-depth research on this before, so that’s where I come in,” says Cailipan. She’s trying to see the world from the periwinkles’ point of view.