by Sara Richmond

Sarah Grady and other archaeology volunteers use this large wooden sieve to sift through soil in search of artifacts. (Photo: Sara Richmond)

In 2012, Sarah Grady was waiting tables at the Old Stein Inn and deciding what to do with her new anthropology degree when a restaurant customer told her about the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center’s Archaeology Lab, located just a few miles from the restaurant. Soon after she became the lab’s second volunteer, working with volunteer lab director Jim Gibb to excavate plots and crunch data. Six and a half years later, Sarah is the lab’s assistant director. The year-round program has grown from just her and Jim to a group of roughly a dozen citizen scientist volunteers who gather every Wednesday to dig and learn about each other’s projects.

The Archaeology Lab is the only all-volunteer lab at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC). Currently the lab hosts 16 ongoing projects, all of which citizen science volunteers have undertaken on their own.

“We guide them,” says Sarah, “but most of them have taken the research into their own hands and are even making appointments with other scientists to discuss.”

Piecing Together the Past

The Sellman House, the oldest building in the Smithsonian, has been standing since the early 1700s.

(Photo: Sarah Grady)

The Archaeology Lab does much of its work around the Sellman House. The brick house near SERC’s main entrance was once part of a tobacco plantation dating back to the early 1700s. Starting in 1729, the Sellman family owned and lived on the property for nearly two centuries before selling it to the Kirkpatrick-Howat family in 1917. The Kirkpatrick-Howats owned it until SERC acquired it in 2008.

Relying on citizen scientists makes it easier for the lab to build connections with the public—connections that are especially vital in archaeology, according to Sarah.

“A big part of archaeology is working with the public,” she says. “You have to think about whose past you’re digging up, because it’s likely not yours.” At the Sellman house, that includes generations of the property’s former owners, enslaved workers, tenant farmers, hired help and others. Citizen science inherently provides a way to share the lab’s work with others.

Volunteers sift through soil near the SERC mansion ruins on an archaeology dig day. (Photo: SERC)

The volunteers range from retirees to students and recent graduates just starting out careers in environmental science. The lab’s youngest volunteer is a high school junior learning how to analyze bones.

“In archaeology, we usually just find pieces,” Sarah says—not the big, intact skeletons you might think of being on display in a museum. The fragments can be tricky to identify, so Jim is helping the student analyze them. It also helps that there’s a giant shelf in the lab with bones from roadkill, which they can compare with excavated animal bones.

The lab’s projects are as varied as its volunteers, but they all have one thing in common: They examine the past effects that humans have had on their landscapes, and urge us to think about how studying the past can help predict the future. One excavation unit revealed three and a half feet of layered sediment, showing how everyday use of the land by the Sellman House families caused erosion. Another trio of volunteers is analyzing pollen around the house. By studying pollen, researchers can tell what types of crops may have grown there over the years. It can also reveal how the Kirkpatrick-Howats’ fondness for non-native trees may have changed the environment.

Unexpected Discoveries

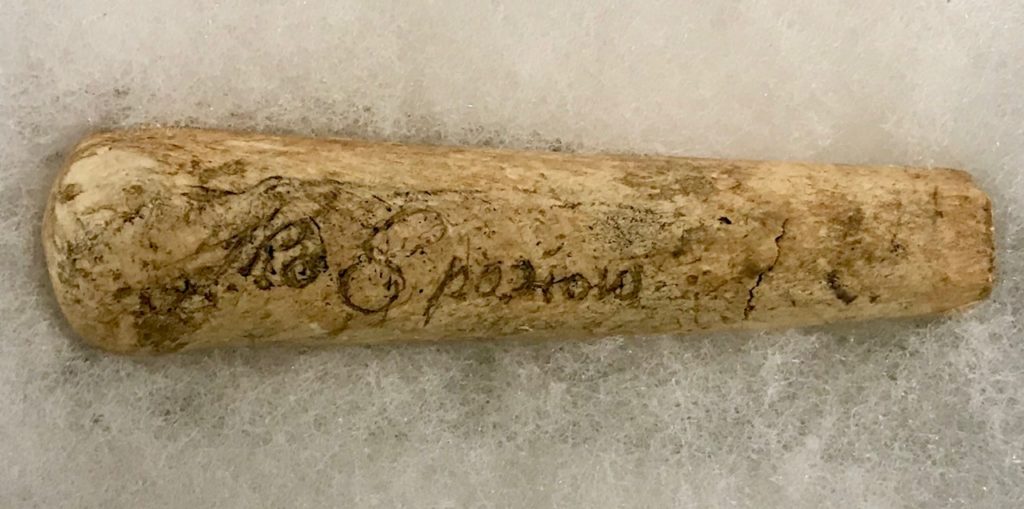

When Sarah first joined the lab, the Sellman House was the primary site. But the increase in volunteers has allowed them to expand. Behind the house, they have been digging at a 17th-century site called Shaw’s Folly. There, they’ve unearthed ceramics from the Mediterranean and North Devon pottery from England. They also found a bone handle, inscribed with the name “Tho Sparrow.” Thomas Sparrow and his family once lived a quarter mile down the road from the Shaws at a site called Sparrow’s Rest. Finding the handle at Shaw’s Folly shows the two families were neighbors, and probably friendly. Sarah says it’s also exciting when the group finds a new type of artifact for the first time, like the Spanish half-real coin from 1774 that they uncovered in the fall.

This bone handle belonged to Thomas Sparrow, who lived at a place called “Sparrow’s Rest” during the 1600s. But volunteers found it on his neighbor’s property called “Shaw’s Folly,” near where the Sellman house now stands. (Photo: Sara Richmond)

Doing research with Jim and the Archaeology Lab took Sarah to places she hadn’t even considered while waiting tables. When she finished her undergraduate degree at the University of Maryland, she thought she might want to become a cultural anthropologist, learning new languages and living among different cultures. Her volunteer work, however, led her to a full-time career as an archaeologist. Today she works as a contract archaeologist, digging at sites that are slated for development before the developer’s work begins. She also teaches anthropology at Howard Community College and co-teaches an archaeology course with Jim at the University of Maryland, where she finished her master’s degree in May. But she still returns regularly to pitch in with the lab.

“We have a family within the lab. We’re really close and have a lot of fun together,” she says. She also enjoys showing the volunteers what she does for a living. “Jim showed me what it’s like to be an archaeologist. That’s what I’d like to be able to do for them too.”

Want to get involved? Contact Alison Cawood, Citizen Science Program Coordinator at cawooda@si.edu.

Visit the Smithsonian Environmental Archaeology Lab Page

Learn more about the Archaeology Citizen Science Projects

Read More:

Time Lords and Ladies of History’s Trash

Learning by Digging: Archaeological Project Explores Colonial Life

What the Plantation Owners Left Behind