SERC biogeochemist Pat Megonigal holds up soil from a marsh in Costa Rica. Marsh soils store vast amounts of carbon, but as temperatures warm, microbes in the soil could release into the atmosphere. (SERC)

by Kristen Minogue

All over the world, marshes are hanging in a precarious balance. Rising temperatures from climate change could help them grow stronger and store more carbon—or cause them to flood and disappear, says a new article from the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC). To find answers, scientists need to look underground.

The article is part of a much larger report on the future of warming oceans, released Monday at the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s annual conference. Tidal marshes sit right on the boundary of the land and the ocean. For humanity, marshes act as Mother Nature’s guardians. They provide habitat for fish and shellfish, filter out pollution in estuarine water, and help shield homes along the coast from flooding. They’re also hot spots of carbon storage, burying carbon 10 times faster than an equal area of forest. Yet much of their fate remains a mystery.

“The response of different plant species to temperature varies a great deal,” says Pat Megonigal, Smithsonian biogeochemist and lead author of the article. “We don’t actually know much about it.”

But this summer, Megonigal’s lab launched a new warming experiment on SERC’s Global Change Research Wetland. There, they may finally get some answers.

Growth and Decay

For all their mysteries, most marshes have one thing in common: Their plants grow better in a warm climate. Scientists have run multiple field studies along the East Coast of the U.S. Each time, they found at least one of the plant species they studied, if not more, put on extra weight when temperatures rose. It’s an encouraging sign. The more plant mass marshes have, the more carbon they can store in soils from the atmosphere.

But the story has a darker underside. Just as rising temperatures speed up plant growth, they could also speed up their decay, making some marshes more vulnerable to collapse as sea levels rise. And that is a mystery no one has solved.

When the soil heats up, microbes underground become more active. They decompose dead material more quickly and release once-trapped carbon back into the atmosphere. Extra plant growth can also jolt the microbes awake, because as plant roots extend deeper into the soil, they inject it with oxygen that enhances decay.

Read more: Climate Change Could Release Ancient Soil Carbon

Growth and decay are twin faces of the same coin. At least, that is the conventional wisdom.

In reality, the question of what makes marshes rot is much murkier. Scientists attempting to model decomposition by microbes have found different answers. Rising temperatures can also change how microbes grow indirectly, by changing the types of plants on a marsh.

“If you take a marsh that’s dominated by Scirpus, and now it becomes dominated by Phragmites or by Iva or by mangrove, that change in plant community composition will affect decomposition rates,” says Megonigal.

And marshes are transforming—whether in Maryland, where the invasive reed Phragmites australis reed is rapidly taking over, or in Florida, where mangroves are displacing salt marshes thanks to warmer winters. What these transformations mean for how marshes store carbon, and for their ultimate survival, remains to be seen.

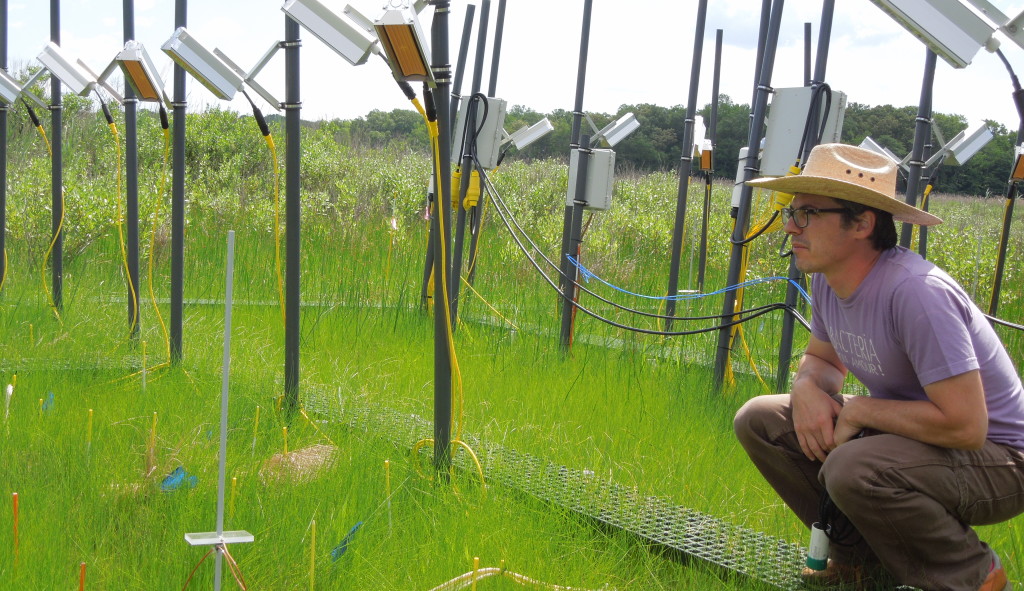

SERC ecologist Roy Rich gazes out over the futuristic global warming experiment he helped build on SERC’s Global Change Research Wetland. (Kristen Minogue/SERC)

Predicting the Future

Genevieve Noyce takes a plant sample to measure on the Global Change Research Wetland. (Kristen Minogue/SERC)

To discover how marshes will react to a warmer world, scientists need experiments that manipulate temperature in the field—something that so far has been scarce.

That’s where the lab’s latest project comes in. Megonigal runs a field site known as the Global Change Research Wetland, where ecologists run futuristic experiments inside chambers with elevated carbon dioxide and nitrogen. Last spring, ecologists Roy Rich and Genevieve Noyce joined Megonigal’s lab to help bring rising temperatures into the picture.

The global warming experiment uses infrared lamps to heat up sections of the marsh aboveground, and more than 1500 feet of underground wires to heat up the soil belowground. By controlling how much marsh temperatures rise, Megonigal, Rich and Noyce will be able to nail down how much temperature impacts how quickly marsh plants grow, and how quickly they decay.

Since the Global Change Research Wetland is similar to many brackish marshes around the world, Megonigal expects what they uncover will apply to other comparable marshes. If rising temperatures do foreshadow the marshes’ eventual collapse, the lab’s discoveries may come in time to help some of them.

“People lose and ecological systems lose when whole categories of ecosystems disappear,” Megonigal says. However, an early warning system like this may tip the balance in their favor.

Read more: Cranking Up the Heat in the “Wetland of the Future”