How California’s Record-Setting Rains Are Reshaping the Ecology of San Francisco Bay

By Ryan Greene, science writing intern

The San Francisco skyline as seen from San Francisco Bay. Credit: Ryan Greene/SERC

The Smithsonian Environmental Research Center’s (SERC) largest West Coast outpost sits on San Francisco Bay in Tiburon, California. The Tiburon branch, affectionately known as SERC-West, serves as the nexus of SERC’s research activities on the western coast of North America. At a whopping 2,462 miles from SERC’s main campus on the Chesapeake Bay in Maryland, SERC-West can feel a bit remote. In an attempt to bridge this distance, we’re launching “Tidings From the Sunset Coast,” a summer story series about all things SERC-West. The first snippet is a story about the wildly wet winter California experienced this year and what all this fresh water means for the marine life in San Francisco Bay. Enjoy!

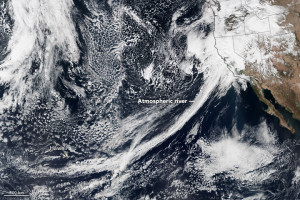

Image from NASA’s VIIRS satellite show one of many “atmospheric rivers” which slammed the California coast this past winter. Credit: Jesse Allen and Joshua Stevens/NASA Earth Observatory

When it comes to rain in California, the last few years have been a feast-or-famine affair. After a bitter drought that sported some of the driest years on record, this past winter brought more precipitation than the northern parts of the state have ever documented. To put it lightly, the weather has been extreme. And while the wet winter has refilled reservoirs and beefed up the snowpack, leading Governor Jerry Brown to end the drought state of emergency in all but four counties, it has also wreaked its fair share of havoc.

Here at SERC-West, scientists have been following another part of this story: the bombardment of freshwater runoff that inundated San Francisco Bay this winter. All the fresh water from the rain drastically reduced the saltiness (a.k.a. salinity) of the Bay. For many plants and animals used to saltier water, this was simply too much to handle. The devastation has been widespread, and according to ecologist Andy Chang, who currently heads up SERC-West, in some areas, the changes to the ecosystem might be less than fleeting.

“We’re kind of expecting to see local extinctions of some species that were here before,” he says.

To Return To Known Places

Most fresh water flows into San Francisco Bay via the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta and the Carquinez Strait. Salty water from the Pacific Ocean flows into the Bay through the Golden Gate. This arrangement means that the North and Central Bays are typically less salty than the South Bay, which has limited freshwater inflow. Credit: USGS; labels by Ryan Greene/SERC

In the 17 years he’s been studying San Francisco Bay, Chang has never seen a winter like this one. Normally, winter rains and spring snowmelt briefly reduce the salinity in the North Bay, where water from the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers drains in through the Carquinez Strait. This winter, so much fresh water poured in that salinity levels tanked all the way down into the South Bay. Half a year later, they’re still not back up to normal.

Chang used to wonder what a huge freshwater influx like this might do to the species living in Bay. He thought of the “Great Flood of 1862,” a legendary West Coast deluge that came right on the heels of the Gold Rush. If something like the Great Flood happened again, would certain species in the Bay just disappear? Would parts of the Bay act as “refuges”? Would the makeup of the marine community change drastically? After this year’s record-setting rains, he now has a chance to tackle some of these questions.

“I’ve spent more or less my entire career waiting to see something like this happen,” Chang says. “And despite that, when it actually happens, it kind of takes you by surprise.”

Luckily, Chang and the scientists at SERC-West are well positioned for this moment. Working as part of SERC’s Marine Invasions Lab, they’ve been monitoring the creatures that hunker down on hard surfaces (the fouling community) in San Francisco Bay for almost two decades. More recently, they’ve also been keeping track of the tiny drifters that float in the water column (zooplankton), the invertebrates that populate the soft sediment (the infauna), and even native oysters and eelgrass.

SERC ecologist Andy Chang uncovers oyster settlement tiles in Sausalito, California. Credit: Ryan Greene/SERC

Much of this work has involved going back to the same sites year after year to survey what’s there. Though this type of long-term monitoring can sound rather humdrum, Chang argues that it’s absolutely critical.

“It doesn’t look sexy until something like [this winter] happens,” he says.

That’s because it’s hard to understand the “extremity” of an “extreme” event unless you have something to compare it to. The spirit of this not-so-glamorous-but-totally-crucial type of research is summed up in these lines from Mónica de la Torre’s poem “The Script”—

To return to known places and act always the same, thus the slightest

change might become apparent.

In the case of California’s wet winter, though, the changes have been anything but slight. In some parts of the Bay, native oysters seem to have completely died off. And in many marinas and harbors, fouling organisms that typically coat jetties, rocks, and dock pilings are all but absent.

“When we go to the marinas, there’s nothing there,” says Michelle Marraffini, a SERC technician who studies marine fouling communities.

SERC technician Michelle Marraffini checks the salinity in a marina where she’s deploying settlement panels. Credit: Ryan Greene/SERC

Rewriting the Slate

For Marraffini and others at SERC-West, documenting the destruction is only one part of the picture. The real question now is what the trajectory of recovery will look like. In the fouling community, for example, many tunicates (a.k.a. sea squirts or ascidians) have simply disappeared. This has totally changed the playing field. Previous work by the lab has shown that, in this part of the world, certain tunicates tend to out-compete other members of the fouling community, claiming space, gobbling up food, and even growing on top of other organisms. With some of these major players out of the mix, who will take their place? And where will they come from?

“What we’re seeing here is that in some ways, the slate is being wiped clean,” Chang says. “That could present a window of opportunity for new invasions to come in.”

SERC researchers are deploying hundreds of settlement panels throughout the Bay to watch how the ecosystem bounces back from such a wet winter. Credit: Ryan Greene/SERC

This spring and summer, Marraffini and her team have been ramping up their monitoring efforts in order to watch the “rewriting” of the Bay’s slate. In their normal annual surveys, they hang squares of hard plastic called settlement panels from piers and docks around the Bay, and then come back three months later to see what’s there. Now they’ve added one-month panels to the mix. This quicker turnaround will give them a higher resolution picture of what’s really going on in the Bay. So far, only a handful of species are showing up. Among these, there’s only one tunicate: Molgula manhattensis.

Another lab member, master’s student Danny Cox, is taking a different tack. Cox is running an experiment to test the salinity tolerance of the invasive clam, Gemma gemma. Since San Francisco Bay is a hotspot for marine invasions, researchers at SERC-West are curious to see how these species respond to extreme freshwater events like this past winter.

“These low salinities kill off most of the things that are used to higher salinities,” Cox says. “What I’m looking at here is a specific invader’s ability to tolerate those low salinities and whether or not they’ll rebound.”

If all goes well, Cox’s experiment will not only help us see how Gemma gemma responds to dramatic salinity shifts, but it may pave the way for future experiments with other invasive organisms.

SERC team members Danny Cox, Jamie Bucholz, and Lina Ceballos collect nonnative Gemma gemma clams for Danny’s experiment. Credit: Ryan Greene/SERC

Taken together, all of this work—from long-term monitoring to species-specific experiments—will help us better understand the underlying ecological forces at work in the Bay. California, like many places, is predicted to experience more droughts and more floods in the coming years. What we learn from this winter might give us a glimpse into what lies ahead. And it may even shed some light on what happened back in the Great Flood of 1862. For now, the slate is being rewritten and the scientists at SERC-West are doing their best to decipher the scrawl.

“There’s gonna be more questions than there are answers this year.” Marraffini says. “We don’t really know. We’ll find out!”

it is amazing to read the response of species to the extreme freshwater events in winter.amazing research and experiments