How the appearance of a nonnative shrimp in the Chesapeake unearthed a 160-year-old naming mystery

by Kristen Goodhue

It seemed like such an innocent catch: two peppermint shrimp, netted in the lower Chesapeake Bay during the 2013 Blue Crab Winter Dredge Survey. But their discovery would send Smithsonian biologist Rob Aguilar spiraling down a rabbit hole of century-old field notes, museum fires and World War II bombings. In a new study, Aguilar and SERC’s Fisheries Conservation Lab finally unraveled a taxonomic knot over a century in the making.

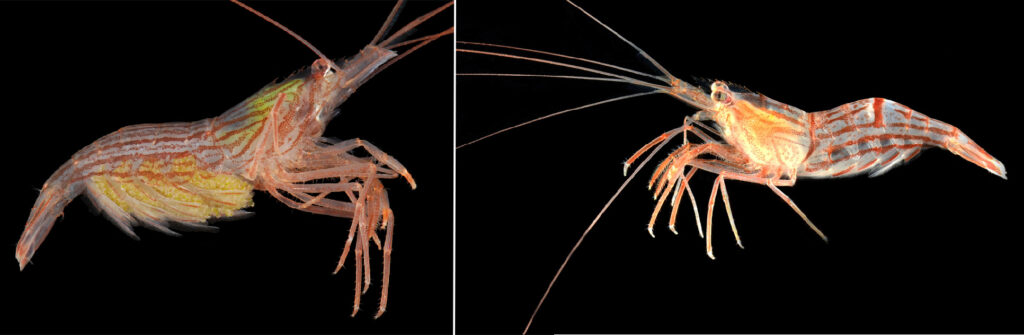

Peppermint shrimp, with their translucent shells and candy cane-like stripes, are among the most popular aquarium shrimp in the world. No one knows how many different peppermint shrimp species exist. Part of the problem: Researchers haven’t always been consistent in how they described the shrimp’s features. Color patterns also aren’t well-document for many species. It’s a recipe for confusion when trying to identify a new catch.

Biologists from the Virginia Institute of Marine Science first found the two shrimp. When they brought them to Aguilar’s desk at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC), he recognized one of them as the Chesapeake’s native species, Lysmata wurdemanni. But the second immediately struck him as something different.

“We knew it wasn’t wurdemanni,” Aguilar said. “We looked at the morphology. It didn’t match anything that we knew of in the Atlantic.”

It did, however, match another species common in the Indo-Pacific: Lysmata vittata.

DNA sequencing from the National Museum of Natural History seemed to confirm the match. At first. The mystery Chesapeake shrimp matched another Lysmata vittata specimen from Taiwan. But other peppermint shrimp from Brazil and Thailand—also labeled Lysmata vittata—were markedly different.

Thus began Aguilar’s journey to unravel a mystery that started in 1860, with another Smithsonian biologist named William Stimpson.

A Tangled Taxonomic Tree

Stimpson first applied the name Lysmata vittata when he found one of the peppermint shrimp during an 1860 expedition in Hong Kong. However, Stimpson’s original description amounted to one short paragraph in Latin, considerably brief by today’s standards.

Aguilar tried to find this original specimen. He traced it to the Field Museum of Chicago, only to discover it was incinerated in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. Furthermore, type material for a supposed subspecies of Lysmata vittata from the Philippines was also destroyed in the World War Two Dresden bombing.

Fortunately there was another, more detailed, description of Lysmata vittata from Hong Kong: by a carcinologist named A. J. Bruce, who collected it in 1986. Aguilar was able to find and examine this specimen. But because the original type material from Stimpson was now ashes, the team needed a “neotype” to serve as the standard for the species. Thus, Aguilar designated Bruce’s specimen as the neotype for Lysmata vittata. Since the nonnative Chesapeake shrimp were identical to the neotype, they also received the title of true Lysmata vittata.

But this only deepened the taxonomic mystery. If the Brazilian and Thai “Lysmata vittata” were not true Lysmata vittata, what were they?

During all this, Aguilar was still going out on the water, collecting as many peppermint shrimp as he could as part of the Chesapeake Bay Barcode Initiative. Over the next five years, he and the Fisheries Conservation Lab, as well as several partner institutions, netted 165 peppermint shrimp in the Bay and analyzed about half of them. They gathered additional species and specimens from Australia and from their MarineGEO partners in Hong Kong. They even downloaded RNA gene sequences from GenBank, the publicly available database run by the National Institutes of Health.

Rauli, Vittata? Tomato, Tomahto.

By this point, Aguilar and his colleagues had discovered a plethora of shrimp bearing the Lysmata vittata name—with different stripes, claw divisions and antennules.

“Over the years there’s been a lot of other species sort of dumped into it….It was sort of a catch all, if you will, for similar-ish species from the Indo-Pacific,” he said.

Take the shrimp from Brazil. When first discovered, scientists thought it was a completely new species: Lysmata rauli. However, another research team noticed how similar the Brazil shrimp was to Lsymata vittata from Thailand. They promptly rechristened it Lysmata vittata, and Lysmata rauli was demoted to a mere junior synonym.

But Aguilar’s team saw some notable differences. The Brazil shrimp—and its counterpart in Thailand—had two sets of perpendicular red stripes. The Hong Kong Lysmata vittata that Bruce found, and the mystery Chesapeake shrimp, had only one set of red stripes running lengthwise down their bodies. Other differences appeared only at the microscopic level: whether the shrimp had an “accessory branch” on one of their antennules, or how many segments they had on their minor claws.

Were the biologists who first named Lysmata rauli truly wrong?

“Our data at this point was saying, well, wait a second, maybe not. Lysmata rauli is likely valid,” Aguilar said.

Restoring Lysmata rauli to full-species status will take more than a single paper. For now, Aguilar and his colleagues divided Lysmata vittata into a complex with two major groups. On one side lives the “Bruce Clade.” This is the “true” Lysmata vittata. It includes Bruce’s Hong Kong neotype and shrimp from other subtropical or temperate regions where it’s presumed native, such as eastern China, Japan, Korea and southern Russia. The Bruce Clade also includes introduced populations in New Zealand and the Chesapeake.

On the other side lives the “Rauli Clade.” It includes the Brazil shrimp that first bore the name Lysmata rauli. Rauli’s presumed native range includes hotter regions of the Indo-West Pacific, as well as introduced populations in Panama and the Mediterranean. The two clades appear to overlap in Hong Kong.

What’s in a name? Do the differences really matter? Knowing the Bruce Clade may prefer cooler, temperate zones could make it easier to predict their movements in the Chesapeake region. Aguilar suspects Lysmata vittata will spread widely in the Mid-Atlantic.

Scientists still aren’t sure what impact a new peppermint shrimp would have on the Bay’s ecosystem. Peppermint shrimp tend to be quite social, Aguilar said, and they often found the native and nonnative species together.

In the meantime, Aguilar and his colleagues are submitting another paper that aims to resurrect Lysmata rauli to full species status. This is not the end of story, however: According to Aguilar, Lysmata rauli appears to be its own complex containing an undescribed species. Another day, another taxonomic mystery to solve.