by Kristen Minogue

Author’s Note: SERC is keenly interested in finding more descendants of the Sellmans, Contees, enslaved Black families, tenant farmers and others who lived and worked on what is now the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. If you wish to be part of documenting our shared history, please send information to Kristen Minogue at minoguek@si.edu.

On March 19, 1685, a major named Thomas Francis took his wife on a boating trip to visit their neighbors across the Rhode River, at a plantation called Tulip Hill in southern Maryland. He never returned. Francis drowned in a boating accident on the way back, at the young age of 42.

His tombstone bore a poetic inscription urging his family not to mourn, but to hope for a reunion after death. One snippet read: “For tho grim death thought fitt to part us here/Rejoyce & think that wee shall once appeare/At that great day when all shall Summond be.”

Fast forward to the 1850s. The field where Thomas Francis lies buried now sits near the intersection of two plantations belonging to the Contee and Sellman families. Both families rely heavily on enslaved Black families to grow wheat, corn and tobacco. Like many wealthy plantation owners, the Sellmans bury their dead in a family cemetery near the house.

Dozens of people lived, toiled and died on the land that today forms the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC). But much remains unknown about their burials. SERC staff knew that Thomas Francis’ tombstone—reportedly the oldest in Maryland’s Anne Arundel County—was on SERC property, but at least a decade had passed since anyone had seen it. Three gravestones once inside the Sellman family cemetery now sit in the nearby All Hallows Church. While small footstones and brick pavers still mark the original graves, SERC staff didn’t know how many other Sellmans lay under the site. There are rumors, but no definitive records, of where the enslaved people had their final resting place.

Today, a team of archaeologists, historians, citizen scientists and cadaver dogs is on the brink of solving the mystery.

Returning to the Past

Left to right: Christine Dunham, Heather Roche, Jim Gibb and two cadaver dogs, Penta and Partner, explore the SERC campus for potential graves. (Credit: Tuck Hines)

Jim Gibb heads the Environmental Archaeology Lab at SERC. It’s the only SERC lab that’s 100% volunteers—including Gibb, who wears the official title “research associate.” Gibb and his crew of citizen scientists have studied the Sellman and Contee plantations for nearly a decade.

Last year the team discovered a patch of periwinkle—a common feature on Maryland cemeteries—around the site of the three known Sellman graves.

“It’s an evergreen, so everlasting life is presumably what they’re saying with that,” Gibb said. Even more intriguing, the periwinkle coated far more ground than would cover three graves, suggesting more people may lie buried beneath. The team began working on the site last fall, with plans to do a more thorough investigation in 2020.

“We’d already started clearing that cemetery with the hopes that we’d be able to see and map the grave shafts,” he said. “But then the great plague hit and that kind of got put on hold. That, and winter weather.”

As SERC closed its doors to most staff and volunteers, any chance of new discoveries in the spring evaporated.

But luck struck in May, when two essential staff were able to return to the site. Program and exhibit coordinator Christine Dunham ventured out with SERC director Tuck Hines. They were working to design an exhibit at the Sellman’s 18th-century house, Woodlawn, and wanted to return to the site of the three Sellman graves. Hines also remembered visiting Francis’ tombstone 10 to 15 years earlier and had noted the GPS coordinates. However, over a decade’s worth of leaf litter made it tricky to find again.

Dunham spotted Francis’s tombstone first, almost entirely concealed by fallen leaves. Hines had brought a machete in his truck for clearing away overgrowth, but they didn’t need it. The tombstone had already broken in two, but some bits of the 335-year-old epitaph remained visible.

Footstone carved with the initials A. S., thought to mark the grave of Anne Sellman, a 19th-century inhabitant of the property. (Credit: Tuck Hines)

They also rediscovered a footstone at the presumed site of the Sellman family cemetery, with the letters A. S. Could it have been for Anne Sellman, granddaughter of the Revolutionary War veteran General Jonathan Sellman? Jonathan, Anne, and Anne’s father, Colonel Alfred Sellman, are the only Sellmans whose burials Dunham has seen records for. But those records indicate their descendants moved those three graves to All Hallows Church.

“There are graves in the churchyard—or rather, there are gravestones,” Dunham said. “One assumes there’s graves.”

Gibb knows from experience that grave removals often don’t get everything, especially with bodies over a century old.

“They pick a few larger bones that are obvious—you know, the skull,” he said. “It’s not like we usually have intact coffins that can be simply picked up and moved. The wooden coffins are usually long gone. And so it’s more of an exercise in excavation rather than exhumation.”

Unmarked Graves of the Enslaved

Rediscovering the Francis and Sellman gravestones, while encouraging, gave the team only a small piece of the land’s history. They revealed nothing about the dozens or hundreds of enslaved who spent their lives working the land, largely without recognition.

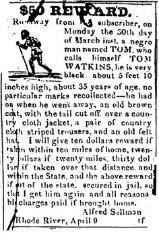

Early 19th-century ad offering up to a $50 reward for capturing Tom Watkins, an enslaved Black trying to escape the Sellman plantation.

“We know some of the names of some of the people that were enslaved, but not all,” Dunham said. Names like Tom Watkins, who ran away from the Sellmans in his mid-30s, and Dennis Simms, who worked on the Contee farm shortly before the Civil War. As an elderly man in the 1930s, he gave an oral testimony recalling the brutality on his former plantation.

Lyndra Marshall, a historian and genealogist with the local Black community, has been helping Dunham track down more names of the enslaved that could be included in the upcoming exhibit.

Before the Civil War, enslaved Blacks did most of the grave digging on Maryland plantations. They didn’t have much say as to where they buried their own. But they had some freedom in how to orient the graves. According to Gibb, the enslaved frequently buried their dead facing a body of water, often on a slope.

To uncover the ultimate fate of those enslaved on the Sellman and Contee plantations, the team needed something that could pick up invisible clues. Enter Heather Roche and her two cadaver dogs.

Roche works with the nonprofit Bay Area Recovery Canines, or “BARC” as it’s affectionately called. She trains her dogs to find the dead by exposing them to odors of human decomposition, like bones and blood.

“It takes longer to train a person. Dogs are easy,” she said.

On a cool Sunday morning in June, Roche brought two black Labradors to SERC: 10-year-old veteran Penta, and 3-year-old Partner, a recruit who flunked out of FEMA’s program because he wouldn’t bark when he found something. Fortunately, Roche doesn’t need her dogs to bark. After circling and sniffing around an area, they simply lie down when they’ve detected a possible grave.

Left: 3-year-old cadaver dog Partner on the footstone thought to mark the grave of Anne Sellman. Right: Heather Roche talks to 10-year-old Penta after she sniffed out the tombstone of Thomas Francis. (Credit: Christine Dunham)

Hines readily admitted being skeptical of using cadaver dogs at first.

“These graves are hundreds of years old,” he remembered telling Roche. “I don’t believe there’s any remains. I don’t believe a dog can do this. It’s one thing if you’re finding a recent body where there’s remains, but something like that, I don’t believe there’s anything left.”

Roche had the two dogs scope out each site separately, without watching each other, so the team would get independent results. Each dog raced out in a star pattern, searching for a scent. When they found something, they would stop, raise their heads, and form smaller and smaller circles until, finally, they laid down.

The first site they zeroed in on had no markings—a flat, forested patch of land covered in shrubs and leaf litter. It didn’t appear on anyone’s list as a possible cemetery.

“We had no suspicion there were graves at this site,” Hines said. But both dogs stopped at it. Perhaps, this may be where some of the enslaved Black laborers finally found their rest.

Tuck Hines talks to Heather Roche at a potential slave burial site both cadaver dogs paused at during their search. (Credit: Christine Dunham)

As the morning progressed, Penta and Partner went on to correctly identify Thomas Francis’s grave and the Sellman cemetery. At both places, the dogs also laid down at other unmarked sites a few feet away, which may contain the remains of more deceased inhabitants.

The team needs more tools to get a clearer picture. They began working with the Maryland Historical Trust to use ground-penetrating radar, a noninvasive technique that can provide radar images of any underground graves. Heather and her herd may return again in the fall, when the terrain is dryer and less overgrown. Gibb also hopes to repair the broken tombstone of Thomas Francis.

In the meantime, SERC is continuing work to rehabilitate the main brick house on the Sellman property and turn it into a historic exhibit. Soon, the nearly 300-year-old house will tell visitors stories of all the cultures that passed through the area—and what footprints they left that still shape the land today.

Read more:

What the Plantation Owners Left Behind

Time Lords and Ladies of History’s Trash

Learning by Digging: Archeology Project Explores Colonial Life

Volunteer Spotlight: Sarah Grady, Explorer of Past & Future Landscapes