New study shows hardened shorelines may mean fewer fish and crustaceans.

by Ryan Greene

A new SERC study shows that both bulkheads (left) and riprap revetment (right) are associated with lower abundance of several species of fish and crustaceans in the Chesapeake Bay and the Delaware Coastal Bays. Credit: SERC

For decades, ecologists have suspected that hardened shorelines may impact the abundance fish, crabs, and other aquatic life. But now they have evidence that local effects of shoreline hardening add up to affect entire ecosystems. A new study by scientists at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) shows that more shoreline hardening means fewer fish and crustaceans in our waters.

Given the predictions for the coming years (i.e. rising seas and more of us living on the coast), this finding is a cause for concern. Many people will likely try to protect their land from flooding and erosion by armoring their shorelines with vertical retaining walls (bulkheads) or large rocks (riprap revetment). But as SERC researchers found in their new paper, published in Estuaries and Coasts, the impact of these hardened shorelines adds up.

Lead author and former SERC postdoc Matt Kornis likens shoreline hardening to littering. While each individual bit of trash isn’t a huge problem, the combined effect can be enormous. Kornis, now a biologist for the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, says the same is true of shoreline hardening. Each individual bulkhead or riprap revetment may not be catastrophic, but cumulatively they can contribute to shrunken populations of ecologically—and economically—important species like the blue crab.

“Shoreline hardening can cause loss of habitats important for young fish, like wetlands and submerged vegetation,” Kornis says. “That may be one reason we observed low abundance of many species in estuaries with a high proportion of hardened shoreline.”

This isn’t all, though. Further analysis by Kornis and others has shown that shoreline hardening changes even the size and types of critters living near the shore. But before we get too deep into what all of this means, let’s take a step back to see what the researchers actually did.

Over the course of about five years, SERC scientists and their collaborators collected more than 600,000 organisms from 587 sites in 39 small estuaries (or subestuaries) of the Chesapeake Bay and the Delaware Coastal Bays.

“It was a huge endeavor,” says Kornis.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Rvgv4HC4m8 &w=575

SERC researchers use a mullet skiff to deploy a seine net for nearshore collection. The video was taken by SERC technician Heather Soulen in 2014. More information about this technique is available in this blog post written by Heather.

SERC researchers use a large seine net to collect organisms at a natural shoreline. Credit: SERC

The scientists made sure to collect organisms that were close to the shore as well as organisms further out in the water. This meant that later, when they looked at their data through the lens of statistics, they were able to establish long-elusive links between what was happening at the local (shoreline) scales and at the scale of entire subestuaries. Additionally, by taking into account different types of land use and the amount of shoreline hardening in each subestuary, they could discover how the choices we make on land ripple into the water.

The short answer, they discovered, was that more wetlands meant more fish and crustaceans, while increased shoreline hardening meant fewer of our aquatic friends. In many ways, this is exactly what they expected to see. But they were surprised to find that when it came to hardening the shore, it didn’t matter what technique was used: Bulkheads and riprap were equally bad.

“We really thought that we would find much higher abundances on riprip…but with the species that we have here we’re not seeing that,” says co-author Denise Breitburg, a marine ecologist at SERC.

What does this mean for the coming years? Sea levels are rising and the number of people living on the coasts is expected to increase. Not only will wetlands need to keep pace with higher and higher waters, but more and more coastline will likely be hardened in an effort to protect against erosion and flooding. If both bulkheads and riprap tend to negatively impact the creatures in our waters, the future looks something less than bright. But according to Kornis, it’s not all doom and gloom.

“The silver lining is that there’s something we can do about it,” he says.

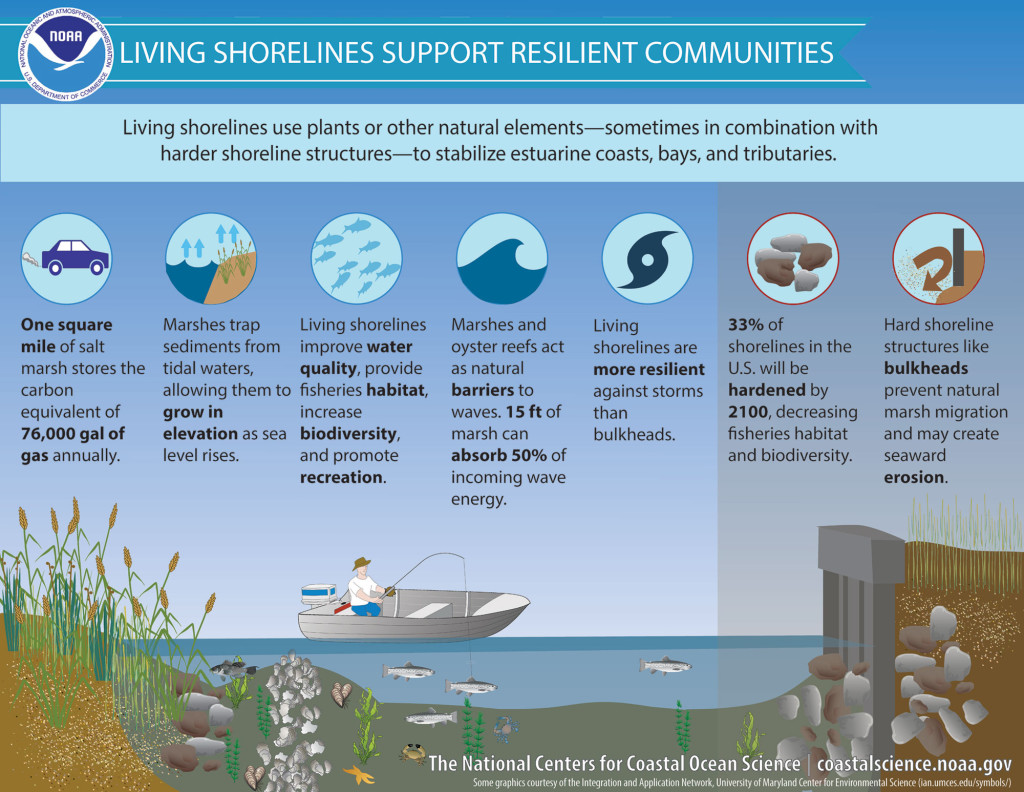

There are, in fact, alternatives to traditional shoreline hardening. Conserving or restoring coastal wetlands is one option. But in cases where this isn’t possible, there are techniques such as “living shorelines” which more closely approximate natural shorelines. Though further research needs to be done on their long-term efficacy, living shorelines do seem to be less ecologically disruptive than traditional riprap or bulkheads.

Living shorelines seem to provide a less ecologically disruptive alternative to bulkheads and riprap. Credit: NOAA/University Maryland Center for Environmental Science

Of course, the construction of hardened shorelines won’t stop overnight. The choices ahead for individuals, businesses, and policymakers are going to be tough ones. But studies like this one provide us with the information necessary to make smart decisions. Cumulative increases in shoreline hardening are not inevitable.

In recent years, the documented negative effects of agricultural runoff have galvanized political will to work toward limiting nutrient pollution into waterways. Kornis imagines something like this might happen with riprap and bulkheads.

“If we can draw similar attention to the shoreline hardening issue, there’s the opportunity to nip this in the bud,” he says.

***

Citation: Kornis, M.S., Breitburg, D., Balouskus, R. et al. Estuaries and Coasts (2017). doi:10.1007/s12237-017-0213-6

Link to article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12237-017-0213-6

For Kristen M, who put this together… The first photos you used, you said that the one on the right is rip rap… That is actually a living shoreline, what you later refer to in the article. The rip rap is placed off shore to create that. You want a photo where the rock is on a steep slope holding back a bank.

Just a heads up

Thanks for pointing that out! We’ve switched the right photo so it now shows a shoreline with riprap.