by Kristen Goodhue

This July, Woodlawn House—the oldest building in the Smithsonian still in its original spot—opened to the public for the first time. Built in 1735 by the Sellman family, it’s now received a new name: the Woodlawn History Center. Visitors can walk through the first floor, encounter centuries-old artifacts and learn about the lives of enslaved and free people who lived on the land. For this feature, we collected a few stories from the exhibit and the people who helped create it.

The Woodlawn History Center is open for free to visitors on select dates (see the Woodlawn History Center visitors page for current dates). It’s located just past the brick security kiosk when visitors first enter the SERC campus.

Dennis Simms: The Enslaved Testifier

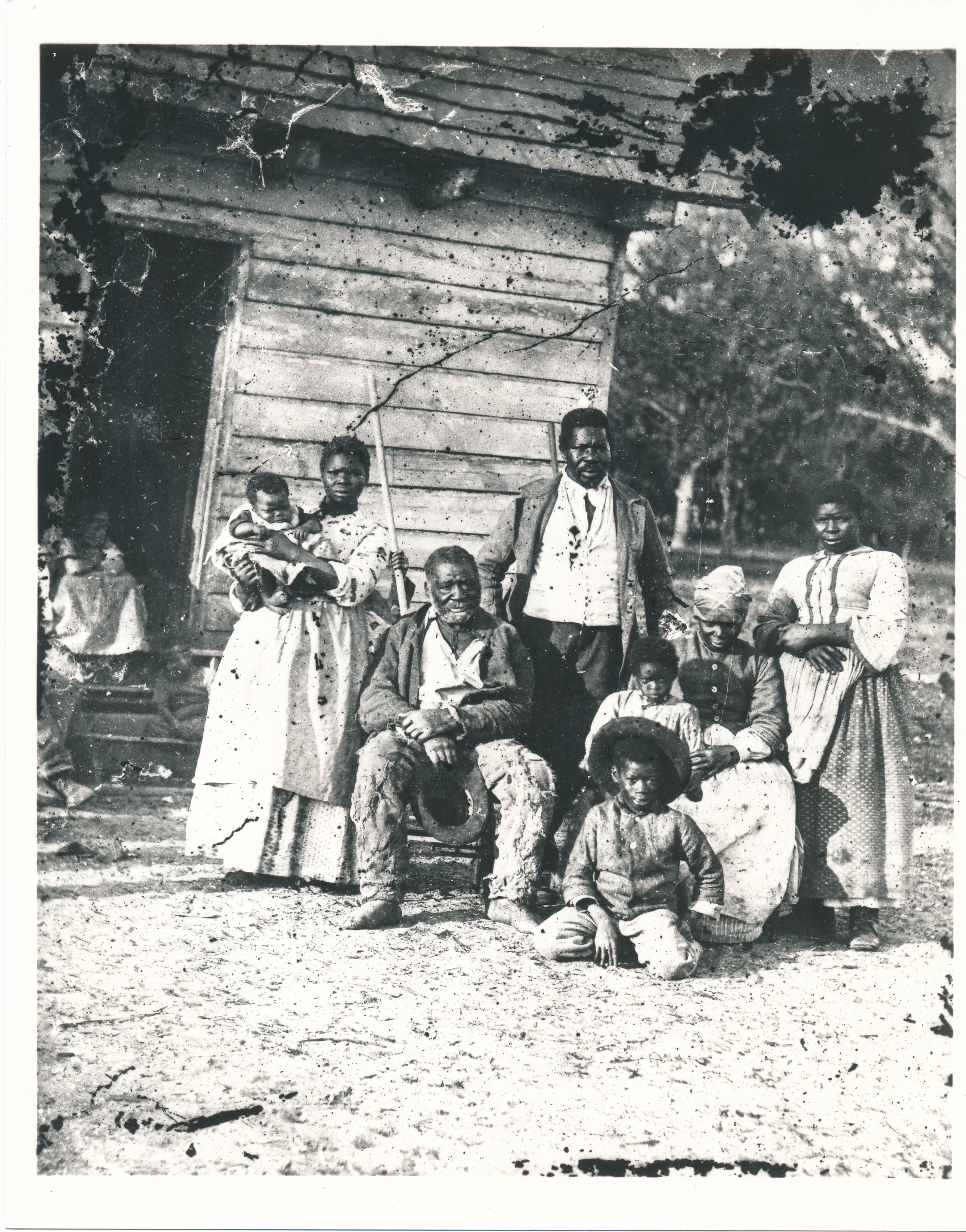

Born in 1841, Dennis Simms worked as an enslaved laborer on the Java Farm, a plantation next to Woodlawn run by the Contee family. There are no photographs or illustrations of him. Other than the color of his skin, we have no idea what he looked like. But in 1937 he left a detailed oral history of slavery at Java. Below are a few excerpts.

“We lived in rudely constructed log houses, one story in height, with huge stone chimneys, and slept on beds of straw.”

“Our food consisted of bread, hominy, black strap molasses and a red herring a day. Sometimes, by special permission from our master or overseer, we would go hunting and catch a coon or possum and a pot pie would be a real treat.”

“We had to toe the mark or be flogged with a rawhide whip, and almost every day there was from two to ten thrashings given on the plantations to disobedient Negro slaves….We all hated what they called the ‘nine ninety-nine,’ usually a flogging until [we] fell over unconscious or begged for mercy.”

“We were never allowed to congregate after work, never went to church, and could not read or write….Sometimes we would, unbeknown to our master, assemble in a cabin and sing songs and spirituals. Our favorite spirituals were—Bringin’ in de sheaves, De Stars am shinin’ for us all, Hear de Angels callin’, and The Debil has no place here. The singing was usually to the accompaniment of a Jew’s [mouth] harp and fiddle, or banjo.”

The full oral testimony of Dennis Simms is in the Library of Congress. SERC owes a great debt of gratitude to Phyllis Jackson, who first brought his testimony to our attention.

Lyndra Marshall: The Genealogist

Lyndra Marshall has been studying Black history in Maryland since 1968, when she first began exploring her family roots. When SERC’s director, Tuck Hines, and program manager Christine Dunham approached her in 2019 about helping with the Woodlawn exhibit, the family connection immediately sparked her interest.

Marshall’s mother bears the Sellman name. Her husband, Roger, also has ties to the neighboring Contee family. “How do I say no? I don’t think I can do that,” she recalled thinking.

But as Marshall knows from experience, piecing together Black history in America is an uphill battle. Written records from the enslaved—even straightforward items like birthdays, full names and family trees—rarely exist.

“They couldn’t tell their story, because they were forbidden to read and write,” she said. Most scholars of pre-Civil War Black history need to rely on records from slaveholders: manumission documents, wills and the occasional want ad for a fugitive. For post-Civil War America, obituaries, military records and church records also provide useful intel. Marshall depends heavily on the Maryland Historical Society and the Maryland State Archives for these documents.

Marshall’s own connection to the Sellmans runs through her mother, Elsie Alverta Sellman Pratt, whose picture appears in the exhibit. She can trace the Sellman side of her family tree to her great-great-great grandfather William Sellman, born in 1825. But there, the trail vanishes. She’s not sure if her family are directly descended from the white Sellmans who lived at Woodlawn or not. However, Marshall is not giving up.

“The main obstacle right now is making that connection from the white Sellmans to the Black Sellmans,” Marshall said. “And I believe if I can go back further than 1825, I can make that connection.”

Virginia Arndt and Betsy Kirkpatrick-Howat: The Descendants

The Sellmans remained at Woodlawn from 1735 until about 1908. By then, their descendants had dispersed across the country—some to other parts of Maryland, and some to Ohio and beyond. Virginia Arndt is the last living descendant of the Sellmans who stayed at Woodlawn the longest.

Arndt’s mother, also named Virginia, was born right after Wesley Witwright Sellman moved his family away.

“I think my grandfather really wanted to stay on the farm,” Arndt said. “When he left to go to Baltimore, I think it was the economics of it. Big family, and he needed a source of income….But he always wanted to farm, and eventually in retirement, after he retired from the insurance business, he bought a small farm out in Sykesville.”

After the Sellmans left, the Kirkpatrick-Howat family took over the property. During the Great Depression, the enterprising Elizabeth Kirkpatrick-Howat managed both Woodlawn and the neighboring Contee land, where Dennis Simms and other enslaved laborers had toiled nearly a century earlier. She raised cattle for dairy and grew hay for the livestock.

“She was quite a businesswoman,” said her granddaughter, Betsy Kirkpatrick-Howat. Eventually, during Betsy’s childhood, the family transitioned to raising cattle for beef.

Arndt and Kirkpatrick-Howat both made substantial contributions to the Woodlawn exhibit, in the form of photos, family history notes and monetary funds. But as their involvement deepened, the two women made a remarkable discovery: They’re related. Arndt and Kirkpatrick-Howat are distant cousins through their great-great-great-great grandfather, Robert Carr.

So perhaps, on some level, Woodlawn House stayed in the family after all.

This is a living history exhibit, and the Smithsonian is always looking for a more complete picture! If you have a connection to or information about any of the families who lived and worked on the Woodlawn or Java/Contee farms, we would love to hear from you. Please reach out to Christine Dunham (DunhamC@si.edu) with your stories.

Learn More About Woodlawn:

Visiting the Woodlawn History Center

Woodlawn House Unlocks Three Centuries of Stories