by Chris Patrick

Darin Rummel, intern in the marine invasions lab at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC), raises a piece of wood twice the length of his arm and slams it onto a dock in the Patuxent River at Greenwell State Park in Hollywood, Md.

The soggy stick crumbles and a white-fingered mud crab scurries from the wreckage. Rummel adds the crab to a modest collection in a Tupperware container and raises the stick above his head again. Connor Hinton, another marine invasions lab intern, wades into a cove of muddy water in search of more crab-concealing wood.

Two weeks ago, Rummel and Hinton hung crab condos off the dock. The small plastic crates contain oyster shells that white-fingered mud crabs like to nestle in, but today the shells are mostly empty save the occasional naked goby, eel, or black-fingered mud crab—unwanted creatures Rummel and Hinton toss back into the river. To find enough crabs for the lab, they have to scour wet, rotting wood.

Dr. Carolyn Tepolt, a SERC postdoc the interns work under, will use some of the mud crabs they collect to investigate the crabs’ adaptation to a body-snatching, parasitic barnacle known as Loxo. Rummel and Hinton spend much of their internship helping Tepolt, but they’ll also use some of the crabs for their own projects.

Hinton, a rising senior at Gettysburg College, wants to know if white-fingered mud crabs parasitized by Loxo are more or less vulnerable to other kinds of parasites.

He’s going about this two ways. In one part of his project, he’s dissecting crabs sampled from several sites across the East Coast, ranging from New Hampshire to Florida. He records the number of parasites in each crab, looking for infection signposts like cysts and worms.

“I’ll compare non-Loxo-infected and Loxo-infected crabs,” says Hinton. “I’m also planning to compare between the different sites up north and down south.”

This sounds simple enough, but dissecting a mud crab the size of a nickel is not so easy. Rummel, who has dissected his share of crabs as a SERC intern, describes their insides as an “amorphous soup of white glop.” It’s difficult to discern what’s crab and what’s parasite.

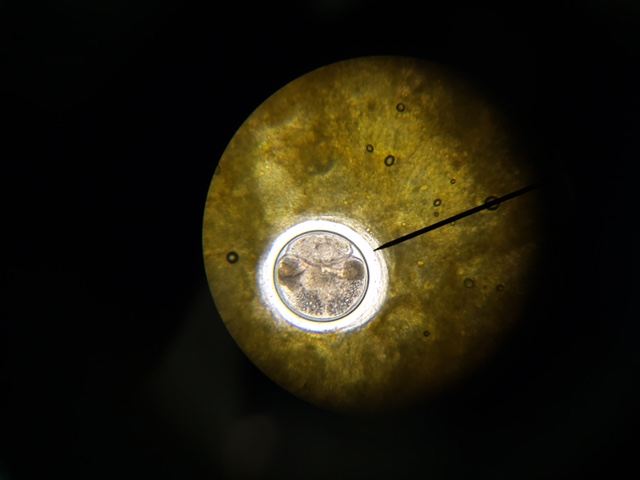

In the second part of his project, Hinton is exposing crabs to a parasite that infects snails. Hinton briefly dries out the snails and then puts them in tanks with the crabs. Any parasites in the snails think their hosts are dying (they’re not) and leave the snail to look for another host, like a mud crab. When Hinton dissects these crabs, which are all from the Patuxent River, he’ll determine if crabs parasitized by Loxo are more or less likely to be infected by the snail’s parasite, a trematode Hinton says “looks like a bubble inside the crab tissue.”

Rummel, recent graduate of the City College of New York, is investigating Loxo. When Loxo infects a crab, it takes total control, making the crab its very own baby-making zombie servant. The parasite spreads itself throughout the crab—female or male—and grows an external sac under the crab’s abdominal apron to brood its young.

But Rummel is removing parasites instead of adding them. He cut Loxo sacs off parasitized crabs from the Patuxent River and now is waiting to see if this allows the crabs to rid themselves of the parasite completely. Loxo prevents its host from molting, so if a crab molts this may indicate that it cleared Loxo from its system.

He’s also keeping half the crabs at low salinity, almost freshwater, and half at high salinity, about half as salty as the ocean. White-fingered mud crabs can handle both freshwater and salty water, but Loxo doesn’t fare well without salt. Rummel thinks the stress of sac removal and low salinity will probably lead to Loxo’s demise, but he doesn’t think the parasite’s death will necessarily allow a crab to clear the infection scot-free.

“What I think is most likely to happen is that these crabs die because their parasites die and they can’t handle it,” said Rummel. A parasite’s death may leave too much dead tissue inside a crab for it to survive. Rummel must wait and see.

Besides collecting local mud crabs for their various experiments, the interns also take turns traveling with Tepolt to collect crabs from states along the East and Gulf Coasts. When Rummel first arrived at SERC, he immediately left for a two-week road trip. While one intern is traveling, the other remains back at lab taking care of the crabs. Hinton recently left with Tepolt to collect crabs in some southern states. When he gets back, he’ll keep dissecting crabs in search of parasites. Rummel, minding the lab while they’re away, will continue to monitor his crabs’ survival.

Looks like Crab can’t leave without parasite after being “invaded”, so it’s pretty bad situation for poor crab. Good experiment though.