by Kristen Minogue

In the coastal waters of the mid-Atlantic, an endangered shark is making a comeback. Led by former Smithsonian postdoc Chuck Bangley, scientists at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) tagged and tracked nearly two dozen dusky sharks over the course of a year as part of the Smithsonian’s Movement of Life Initiative. They discovered a protected zone put in place 15 years ago is paying off—but it may need some tweaking with climate change.

Dusky sharks are what Bangley calls “the archetypal big, gray shark.” Born three feet long, as babies they’re already big enough to prey on some other shark species. But they’re slow growing. It can take 16 to 29 years for them to mature. If their populations take a hit, recovery can take decades.

The sharks’ numbers plummeted in the 1980s and 1990s, when well-intentioned managers offered sharks as an “alternative fishery” while other stocks, like cod, were collapsing. The overfishing that followed wiped out anywhere from 65 to 90 percent of the Chesapeake’s duskies, said Bangley, now a postdoc at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia. Managers banned all intentional dusky shark fishing in 2000. Five years later, they created the Mid-Atlantic Shark Closed Area encompassing most of the North Carolina coast. The zone prohibits bottom longline fishing, which can accidentally ensnare dusky sharks, for seven months of the year.

But is the partial refuge working?

A dusky shark Smithsonian biologists tagged near Ocean City, Maryland. (Credit: Danielle Hall/Smithsonian Ocean Portal)

Doing Surgery on a Shark

Scientists put these black acoustic tags inside sharks to track their journeys. The tags emit “pings” that receivers along the shore can pick up when a shark swims nearby. (Credit: Jay Fleming/Smithsonian)

In the latest study, published in Marine and Coastal Fisheries, Bangley and SERC’s Fisheries Conservation Lab fitted 23 dusky sharks with special acoustic telemetry tags. As the sharks move, their tags emit pings that hundreds of receivers along the East Coast can pick up whenever a shark passes nearby, enabling scientists to see where sharks are migrating and when.

To insert the tags, scientists have to become shark surgeons. After catching a shark, the scientists flip it onto its back, which puts the shark into a state of “tonic immobility” similar to anesthesia. Then, they place a small telemetry tag inside the shark’s belly. Throughout the surgery, the shark has a hose in its mouth to keep seawater flowing gently over its gills. The entire process takes just five to 10 minutes.

Duskies aren’t the only shark species SERC scientists have tagged, or the most dangerous. Young sandbar sharks are much more difficult to manage, according to Bangley.

Chuck Bangley holds a blacknose shark, another shark species he has been tagging along the U.S. East Coast. (Credit: Jay Fleming/Smithsonian)

“The juvenile sandbars tend to really thrash around and snap at you a lot. They’re a little bit panicked,” he said. “The duskies just seem annoyed.”

Once the sharks have their tags, hundreds of stationary receivers along the coast are waiting to pick up their signals. That massive number is key to the project’s success. Working alone, a single research team may be able to put a mere handful of receivers in the water and hope a tagged shark swims close enough to be detected. But thanks to a grassroots effort called the ACT Network (short for “Atlantic Cooperative Telemetry Network), nearly 200 scientists have joined forces to put receivers all along the Eastern Seaboard and share their data. With so many receivers on the lookout, biologists can create a much higher-resolution map of species’ favorite travel routes.

“The dusky shark project is a great example of how valuable having a regional network is for tracking migratory species,” said co-author Matt Ogburn, head of SERC’s Fisheries Conservation Lab.

A Refuge Out of Sync?

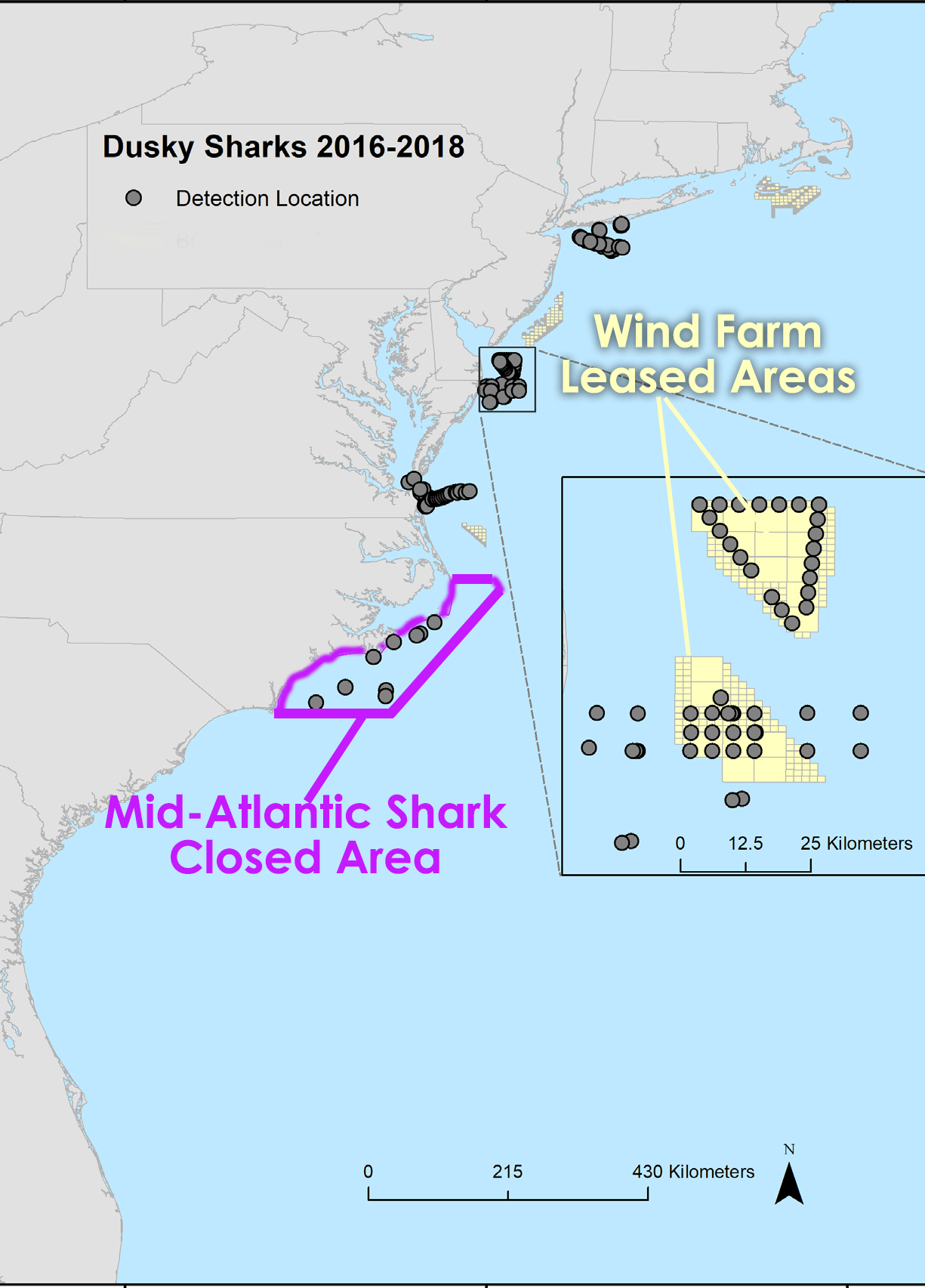

As the duskies migrated up and down the coast, their pinging tags allowed the team to track their movements. They discovered dusky sharks use the protected Mid-Atlantic Shark Closed Area, but not exactly when people expected. The zone prohibits bottom longline gear from January through July. However, tagged dusky sharks entered the zone from November through May. Bangley suspects this could be a sign that waters are warming, and the sharks are moving north sooner in the year. The unprotected months of November and December could put duskies in danger.

The team also detected sharks in areas leased for offshore wind farms. While the construction noise could temporarily drive sharks away, Bangley said the permanent structures could eventually attract prey that would draw the sharks back.

“You might get some kind of short-term pain and some long-term gain,” he said.

Should North Carolinians be worried about having dusky sharks for neighbors? Not really, according to Bangley.

“Dusky sharks only really occur that close to shore during colder months, or as juveniles,” he said. “They’re really not thought to be a real threat to people as far as bites on human beings are concerned.”

Dusky sharks have proven one thing for certain: With the right protections, even a species on the brink of local extinction can return.

“This is a species that we were afraid was going to be impossible to bring back,” Bangley said. “And it’s actually coming back to the point where now we’re having to think about things like, all right, now how do we manage interactions between these species and people? It’s a good problem to have.”

Learn more:

Following The Movement Of Life: Tagging Sharks and Rays

For The First Time, Biologists Track Cownose Rays To Florida and Back

Video – Shark Tagging: Smithsonian Movement Of Life Initiative