by Jaylene Lopez

In late summer 2022, San Francisco Bay experienced an unprecedented toxic algal bloom that caused a red tide across the bay, leading to the largest fish kill in years. Experts are still trying to figure out its cause.

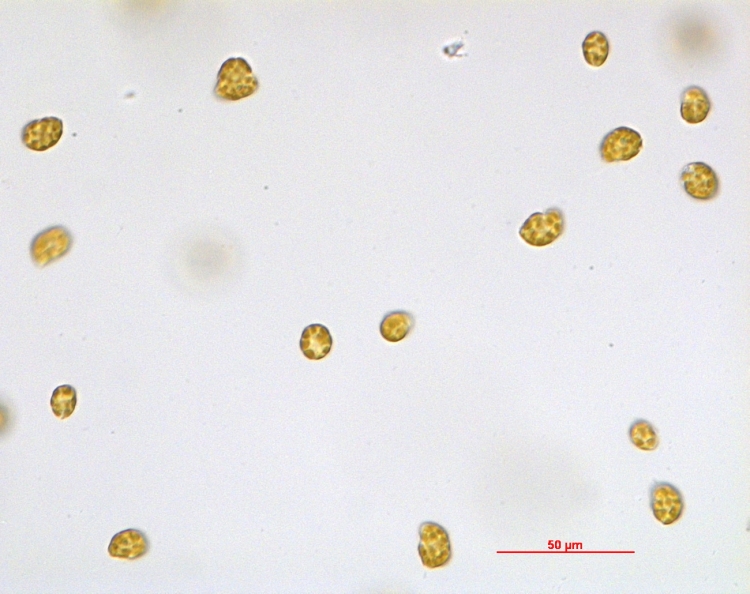

The massive bloom of the microalga Heterosigma akashiwo (H. akashiwo) in San Francisco Bay may have been driven by record heat, increased nutrient richness in the bay from sewage, or possibly both. Throughout September 2022, the Bay Area experienced some of the highest temperatures ever recorded. The heat wave worsened the algal bloom, since warmer water allows most algae to grow at faster rates.

However, it wouldn’t be fair to blame the heat wave alone. The cause is difficult to pinpoint because of the unpredictable nature of Heterosigma akashiwo, which can apparently bloom at any time. Blooms of some other species can be predicted, but toxicity in the blooms, like the one that happened in San Francisco, cannot be. Although not known to be toxic to humans, this algal species is usually toxic to fish.

At the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center’s branch on San Francisco Bay (SERC-West), one project may have caught evidence of this historic moment. Biologists with SERC’s Marine Invasions Lab have placed plates under the docks of marinas every summer since the year 2000 to track invasive species that make it to San Francisco. These plates mimic the bottom of boats that travel to and from the Bay area.

During the fall of 2022, however, these plates served a double purpose. SERC scientists, including fouling plate intern Karina Lang, have been studying the plates since June. During the bloom, the plates tracked an unprecedented amount of death at this time of year and highlighted the extent of the algal bloom’s impact around San Francisco Bay.

Have A Lot On Your Plate?

This fall, I went out into the field with Lang to investigate and document the event. We went to several marinas throughout September and October to check on the plates scientists had left out during the red tide.

Lang jumped right into this project when the bloom started. “I thought that this was the perfect way for me to still work in the marine fouling community and have my research be related to SERC research, while also having a conservation aspect,” said Lang.

The differences between the plates were like night and day.

Areas hit hard by the algal bloom, like San Leandro, had plates that were devoid of life, covered only with mud and other dead matter. Other places, such as Berkeley, were seeing some improvement. Meanwhile, regions unaffected by the bloom, like North Bay, were teeming with life.

Equally dangerous is the effect that algal blooms can have on the oxygen in the water. Algae produce oxygen because they are photosynthetic organisms. However, when the algae stop growing and get decomposed by bacteria, oxygen levels can plummet.

Whether the fish were dying from eating the algae, or suffocating from the low dissolved oxygen in the region, remains unknown. However, we do know that the dissolved oxygen was low enough to kill fish and invertebrates. There aren’t many dissolved oxygen monitoring stations around San Francisco Bay, so that makes Karina’s project that much more important.

It wasn’t just the plates that were empty—tons of empty oyster shells lined the bottom of marinas. Dead oysters and sludge fell from Lang’s hands as she inspected the dock for any life.

The bloom stuck around for weeks. “Sometimes you could still see the streaks of the bloom. You could see parts where it was denser,” said Lang. “There was a lot of mortality on the plates. Some were even completely bare.”

Spread of the Red Tide

Experts believe the Lake Merritt and Alameda areas on the East Bay are the most likely source of the bloom, because of its considerable amounts of Heterosigma and a higher local population.

From there, the bloom spread outwards towards the North Bay and to the southern end of the Bay. It appears that these other areas also had great growing conditions for Heterosigma.

Temperature also played a role. “Some areas get warmer than others. Notably, the shallowest and sunniest areas will warm up most rapidly,” said Andy Chang, an ecologist at SERC. “Lake Merritt fits that description, as do various parts of the South Bay: San Leandro, Palo Alto, Redwood City.”

Areas with lower overall income and greater racial diversity tend to coincide with lower water quality due to pollution. This event may have even further lowered the dissolved oxygen levels in these regions. That is perhaps why Oakland may still have had lower oxygen levels weeks after the bloom, and why Berkeley is seeing improvement.

East Bay was one of the hardest hit areas, since the bloom is believed to have started in the area.

Raymond Corral, Dockmaster at the Alameda Marina, may have unknowingly predicted the effect of the algal bloom on birds. One of the biggest fish kills in years is now possibly going to affect an important food source for birds in the area, including those migrating along the Pacific Flyway this fall and winter, since San Francisco Bay is a critical stop on the route.

“What I’ve noticed is that the birds have dissipated here in this area,” Corral said. “They haven’t been eating the fish.” The algae itself is not toxic to the birds. But their food source, bay area fish, died at unprecedented levels. Dead fish, killed off by either the bloom’s low oxygen levels in the water or the toxins in the algae, crowded onto beaches on the south bay.

But some areas had a little extra protection. Windy areas, deeper waters, or areas with greater mixing due to strong currents (like the central bay near Golden Gate and some parts of North Bay), experienced little to no red tides. Conditions like these make it more difficult for algae to obtain sufficient light and develop high-density blooms.

Late Bloomers

Long after the original algal bloom dissipates and the tinge clears, remnants will still remain hidden in the water below. SERC will continue to study this in the years to come. “In general, this is part of a line of work in the lab to understand the effects of increasingly extreme events as climate change impacts manifest themselves,” said Chang.

Dr. William Cochlan, senior research scientist and biology research professor at San Francisco State University’s Estuary & Ocean Science Center, explained the cyclical nature of blooms. “When these cells are stressed, they form cysts, sort of like a seed, that are very environmentally resilient.” said Cochlan. “They sink down to the sediments and just wait for a better day….They can wait hours, days, weeks or years. When conditions are better…the cysts [release the cells] and you’ve got potential for a bloom once again.”

In other words: Get ready, San Francisco Bay, you’re probably going to see more blooms of H. akashiwo!

Lang’s work on this project highlights how important it is to be aware of local environmental events, so we can prepare for the future that will transpire from climate change and other major events.

To fix the environmental issues that arise, research at the SERC-West lab is critical. “The problems aren’t going to go away as quickly as we want them to….The San Francisco Bay is not equipped to handle blooms like this,” said Lang.

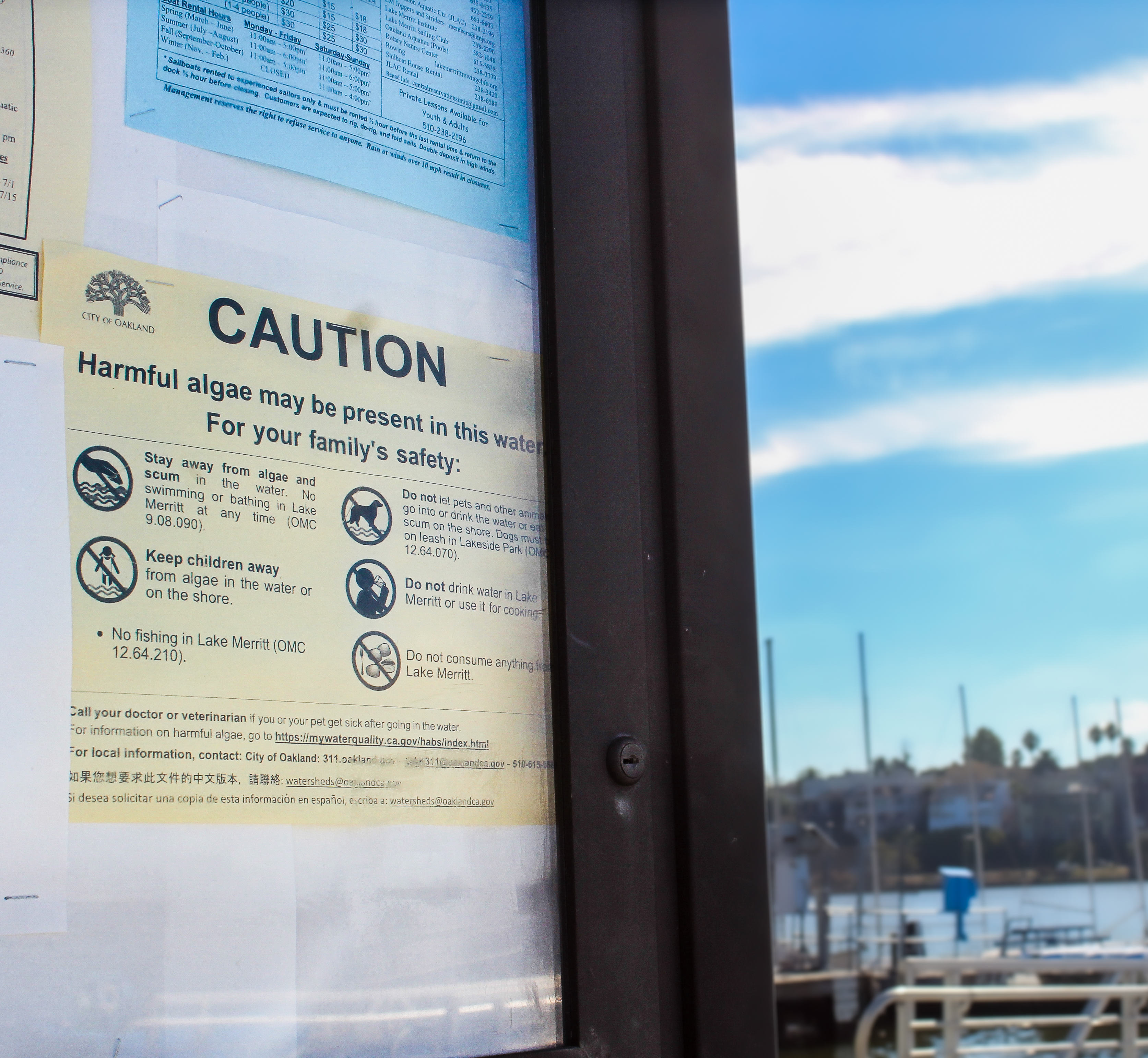

For now, the algal bloom has dissipated, and the bay water is clear again. The bloom is unlikely to affect humans, but experts urge residents to be careful around red tides, just in case. Don’t swim in discolored water, and don’t consume any of the dead fish beached on the bay.