by Heather Soulen

Last week Nature magazine published a news piece about how supplies of agar, a research staple in labs around the world, are dwindling. Agar is a gelatinous material from red seaweed of the genus Gelidium, and is referred to as ‘red gold’ by those within the industry. Insiders suggest that the tightening of seaweed supply is related to overharvesting, causing agar processing facilities to reduce production. Most of the world’s ‘red gold’ comes from Morocco. In the 2000s, the nation harvested 14,000 tons per year. Today, harvest limits are set at 6,000 tons per year, with only 1,200 tons available for foreign export outside the country. In typical supply and demand fashion, distributor prices are expected to skyrocket. As a result, things could get tough for scientists who use agar and agar-based materials in their research.

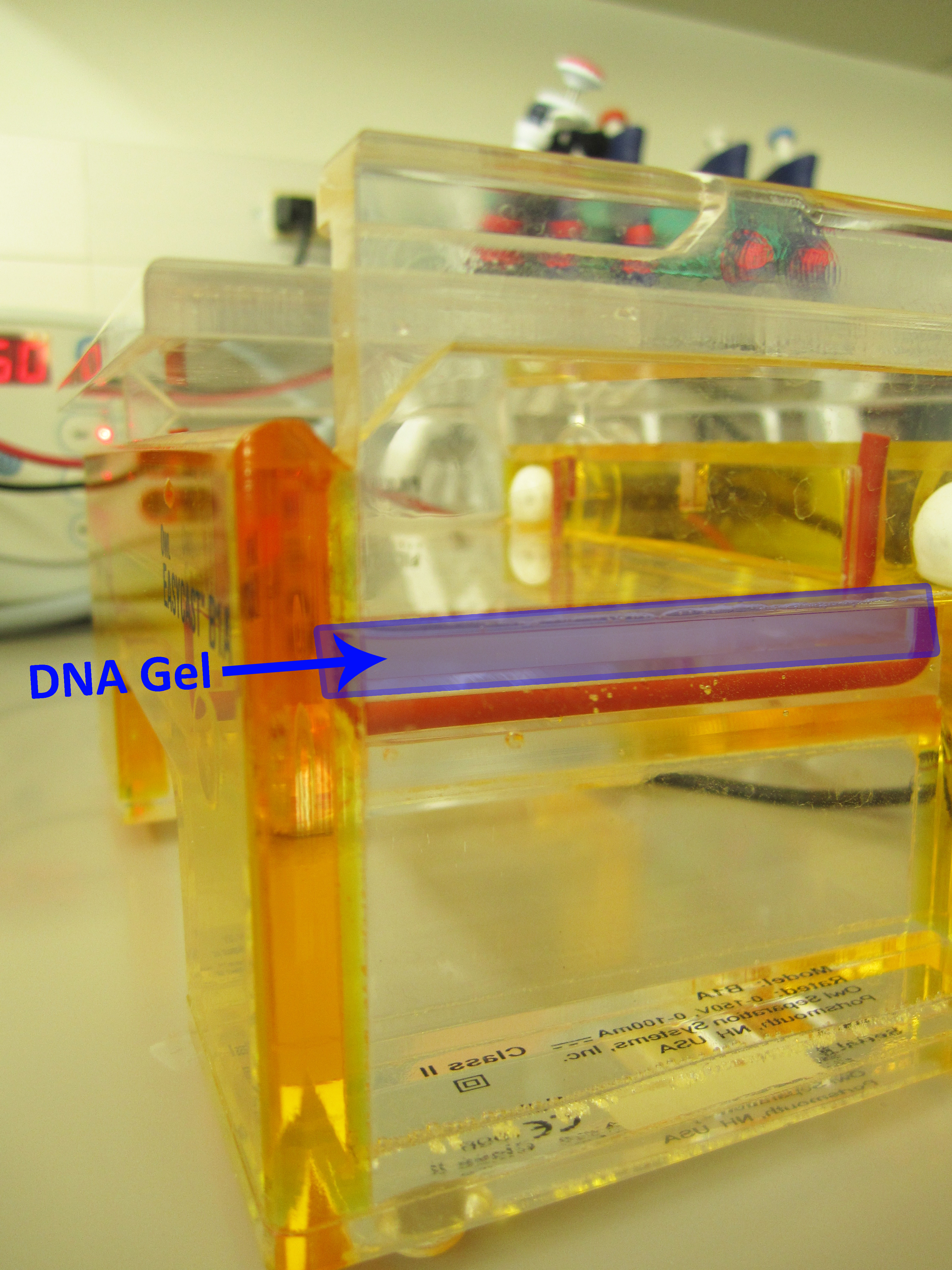

Agar is a scientist’s Jell-O. Just like grandma used to make Jell-O desserts with fruit artfully arranged on top or floating in suspended animation within a mold, scientists use agar the same way. Bacteria and fungi can be cultured on top of nutrient-enriched agar, tissues of organisms can be suspended within an agar-based medium and chunks of DNA can move through an agarose gel, a carbohydrate material that comes from agar. Agar and agar products are the Leathermans of the science world.

How We Use Agar to Answer Ecological Questions

Scientists at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) use agar and agarose, an agar-based material, in a variety of ways. Here are just a few ecological and conservation studies that could be impacted by agar limitations:

Orchid Cultivation and Microbiome Assay

The Plant Ecology Lab, Molecular Ecology Lab and North American Orchid Conservation Center (NAOCC) is involved in several orchid studies that require agar. Powdered agar is enriched with nutrients, mixed with water, heated and poured into petri dishes and slants, test tubes placed at an angle, and allowed to cool and solidify at room temperature. These serve as a growth medium and a nutrient-rich food source for culturing NAOCC’s 500 fungal species. It also cultures the Molecular Ecology Lab’s fungi for studying fungal microbiomes and associated endobacteria, bacteria living inside fungi, to understand the complexity of orchid-microbe interactions, orchid health and growth. Nutrient-enriched agar is also used for orchid seed germination.

DNA Studies

The Molecular Ecology Lab uses agarose gels to separate chunks of DNA from orchid-fungal microbiomes and fungal endobacteria DNA that later can be sequenced and identified using an online DNA database. They’ve also used agarose gels for DNA studies looking at the genetic variation in native smooth cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora) in nutrient pollution studies and genetic variation in populations of the invasive common reed (Phragmites australis).

The Marine Invasions Lab use agarose gels for DNA analyses to identify parasitic protozoans (Perkinsus, haplosporidians, gregarines) in seawater and sediments, and in bivalve tissues collected along a north to south gradient to look at the diversity and distribution of the different parasite species. Agarose gels also allowed them to discover the presence of eastern oysters (Crassostrea virginica) and another non-native oyster (Saccostrea) in Panama, and to look for pathogenic slime molds (Labyrinthula) associated with seagrasses.

Bivalve Disease Culturing

Head technician Rebecca Burrell places oyster tissue for dermo disease analysis in media containing agar

The Marine & Estuarine Ecology and Fish & Invertebrate Ecology Labs use a product called Ray’s Fluid Thioglycollate Medium (RFTM), which contains about three percent agar, to culture Dermo (Perkinsus marinus). Dermo is a disease that can cause severe mortality in bivalves like the eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica) and soft-shell clams (Mya arenaria) in the Chesapeake Bay and beyond. The common method used for Dermo detection requires tissues to be suspended in an anaerobic and nutrient-rich environment. Because agar suspends materials, aids in nutrient delivery and creates an air-tight decomposition free barrier around the culture materials, it’s an obvious addition to the RFTM product.

Synthetic Agar

There are synthetic agar products available for media and culturing purposes, but some are toxic to certain fungi and orchid seed species. Synthetic agarose products used for making DNA gels also have pros and cons – cons being that acrylamide (powder or solution form) is a neurotoxin, bubbles can form in gels causing unreliable DNA separation during electrophoresis, there’s a much longer wait time for the gel to set and be ready for use, and the synthetic form is often more expensive than agarose.

Agar’s Other Wonders

Agar is also found in everyday products outside the lab. The commercial food and other industries use it to make a myriad of products, including breads and pastries, processed cheese, mayonnaise, soups, puddings, creams, jellies and frozen dairy products like ice cream. Home brewers, wine makers and cocktail enthusiasts use agar as a clarifying agent, and serious brewers and wine makers use it as a way to collect, store and grow wild yeast cultures. Vegetarians and vegans use agar as a substitute for gelatin, an animal-based product. Paper and fabric companies use it for sizing, or protection from fluid absorption and wear of their products.

Life without Agar Is No Life at All

‘Tis the season to for celebration, feasting and reconnecting with friends and family. Now imagine it without bread for comfort foods like soups and stews, pastries with morning coffee or tea, mayonnaise for game day sandwiches, a hefty dollop of whipped cream on pie, jelly for toast, English muffins or scones and wine for the holiday dinner. Of course, some agar substitutes may be used in food products, but in science, some substitutes cannot be used as they are toxic. Without a substitute, researchers will be forced to buy agar at double or triple the original projected amount, but with such strict unprecedented harvesting limitations the price could get higher. Questions are now surfacing. Where will the funds come from to cover this extra unexpected cost? Where does that leave research studies and conservation efforts? Scientists, managers and policy makers could be facing some tough decisions as the economic impacts of ‘red gold’ restrictions trickle through the research ecosystem.