Posted by Kristen Goodhue on January 30th, 2012

by Kristen Minogue

Downy rattlesnake orchid. (Melissa McCormick/SERC)

Orchids can be notoriously picky plants – a fact which makes conserving the endangered ones a difficult job for ecologists. In a paper published this month in the journal Molecular Ecology, SERC ecologists revealed that an orchid’s survival hinges on two factors: a forest’s age and its fungi.

Roughly 10 percent of all plant species are orchids, making them the largest plant family on Earth. But habitat loss has rendered many threatened or endangered. This is partly due to their intimate relationship with the soil. Orchids depend entirely on microscopic fungi in the early stages of their lives. Without the nutrients orchids get digesting these host fungi, their seeds often won’t germinate and baby orchids won’t grow. And not every fungus works for every orchid. If there’s a mismatch, the fungus is effectively useless.

But while researchers have known about the orchid-fungus relationship for years, very little is known about what the fungi need to survive. And it turns out the fungi can be just as picky as the orchids.

Click to continue »

Posted in Ecology | 4 Responses »

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on January 24th, 2012

by Kristen Minogue

Blue mussels (Credit: Meriseal)

Some species can survive just about anywhere. Take blue mussels, a group of shellfish whose habitat stretches from the Arctic to the Mediterranean. Over the last several decades, biologists have thrown all kinds of tests at them – heat, cold, saltwater, freshwater, low oxygen. They’ve even tried drying them out. Almost nothing fazes these animals. For invasion scientists trying to figure out how far they could spread, that’s a scary prospect.

Click to continue »

Posted in Ecology, Fisheries, Interns, Invasive Species, Publications | 3 Responses »

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on January 9th, 2012

by Monaca Noble

SERC's Green Village during Snowmageddon February 2010 (Stephen Sanford)

Remember Snowmageddon 2010, the east coast storms that dumped up to three feet of snow over the mid-Atlantic? The February snowstorm was the largest in the region in nearly 90 years, resulting in the heaviest snowfall on record for Delaware (26.5 inches) and the third heaviest snowfall in Baltimore (24.8 inches). The storm made a big impression on Dr. João Canning-Clode and other scientists at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, who began to wonder if the storm, and the December/January cold snap that preceded it, would lead to the deaths and potential disappearance of marine invaders from southern climates.

Click to continue »

Posted in Climate Change, Ecology, Extreme Weather, Invasive Species, Publications | 1 Response »

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on December 23rd, 2011

by Kristen Minogue

Leaf shredded by insects. Credit: Marina LaForgia

It’s a trick worthy of any spy thriller: to elude an enemy, hide among something it won’t notice. Or, to be extra safe, something it finds incredibly disgusting. It turns out the same strategy can work for plants that don’t want to get eaten. Sometimes.

For the last seven months, intern Marina LaForgia has kept tabs on tree saplings in more than a dozen different environments and watched the game of ecological survival play out. As she tracked their progress, she searched for an answer to a deceptively simple question: Is diversity good for plants? When it comes to the food chain, will hungry herbivores pass over tasty plants if they’re surrounded by less palatable ones?

Click to continue »

Posted in Ecology, Interns, Publications | 8 Responses »

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on December 6th, 2011

by Monaca Noble

On a thin strip of land between Bolinas Lagoon and the Pacific Ocean lies the neighborhood of Seadrift, a community battling an invasion of crabs that have taken over their lagoon.

European green crab (BrentMWilson)

Seadrift is a small subdivision at the northern tip of Stinson Beach, Calif., sandwiched between Bolinas Lagoon and the Pacific Ocean on a narrow sand spit. It surrounds a small enclosure called the Seadrift Lagoon, an artificial lagoon created for the subdivision. It’s a popular site for visitors, and the lagoon provides recreational enjoyment for the entire community. But for the last two decades one unwelcome visitor has proven to be very bad company.

Click to continue »

Posted in Classes and Events, Ecology, Invasive Species, Participatory Science | 5 Responses »

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on November 23rd, 2011

by Kristen Minogue

Bat infected with deadly white-nose syndrome.

(U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

The last Western Black Rhino appeared in Cameroon in 2000. Now they’re gone, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, which declared the rare subspecies officially extinct Nov. 10. As thousands more species go extinct across the world every year, the Chesapeake Bay watershed is fighting to save its own endangered flora and fauna. Maryland counts 362 plants and animals on its endangered list – and that’s not including the ones that have already been wiped out from the state. Whales, bats, turtles and orchids: here are six of Chesapeake’s most wanted.

Click to continue »

Posted in Ecology, Fisheries, Water Quality | 11 Responses »

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on November 4th, 2011

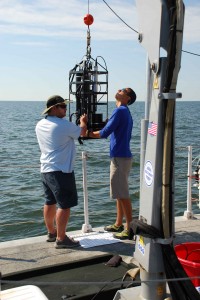

Above: One perk of student research at SERC. Photo courtesy of the Phytoplankton Lab

It’s impossible to work here without some compulsion to understand the natural world – whether it’s colonial tunicates that bear a

creepy resemblance to the Borg or

endangered orchids that need microscopic fungi to survive. So when Smithsonian Magazine launched a

“Why I Like Science” series on their blog

Surprising Science, we took full advantage of the opportunity to share our enthusiasm. Here’s how four staff responded when asked why science is cool.

Click to continue »

Posted in Publications | 1 Response »

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on October 5th, 2011

by Kristen Minogue

Credit: NOAA Photo Library

Let’s face it, the East Coast has had an incredibly bizarre year. In 2011 so far, we’ve seen the coldest January on record, the hottest month on record (July), a hurricane, a tropical storm and an earthquake (we’re not even going to touch the last one – we’ll leave that to our colleagues at

Natural History). And to top it off, August and September drenched us with uncharacteristically high rainfall. While SERC tends to focus on the long-term picture rather than brief snapshots, this year has prompted more than a few raised eyebrows among our scientists. What does it mean for the environment? What does it mean for Chesapeake Bay? And can any of it be linked to climate change?

Click to continue »

Posted in Climate Change, Ecology, Extreme Weather, Invasive Species, Publications, Water Quality | 3 Responses »

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on October 4th, 2011

by Monaca Noble

Over the last two years, more than 150 volunteers have been working to remove an invasive Asian kelp from marinas in San Francisco Bay.

Undaria pinnatifida, grown to maturity. (Credit: SERC)

, also known as Asian Kelp, Wakame or just Undaria, is a fast-growing kelp that fouls ship hulls, nets, fishing gear, moorings, ropes and other marine structures. As a fouling species, Undaria causes economic and ecological damage and competes for light and space with native organisms, altering their ecosystems. The kelp is native to the northwest Pacific – Korea, China, Hong Kong, and Japan – where it is cultivated for food. But starting in the 1980s, it appeared in France, New Zealand, Australia, Argentina, and California.

Click to continue »

Posted in Invasive Species, Programs | Comments Off on How the West Was Won (Back)

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on September 16th, 2011

by Kristen Minogue

On a hot afternoon in July, a team of researchers sailing down Chesapeake Bay stumbled across a cluster of striped bass floating in the water. About a dozen of the iridescent black and silver fish bobbed at the surface near the ship’s bow. All of them were dead.

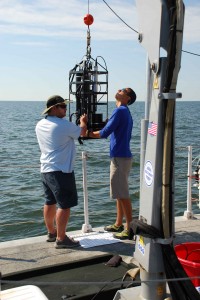

Scientists prepare to measure how light interacts with particles in the Bay. Credit: Carlos DelCastillo

The fish kill came out of a low-oxygen zone near Annapolis, just one symptom of the Bay’s declining health. Overflows of nutrients from farms and cities have fueled massive growths of algae that cut off light and oxygen to the Bay’s lower levels.

“There was a very quiet moment between everybody on the boat,” recalled Vienna Saccomanno, one of the Smithsonian research interns aboard when it was discovered. “You kind of knew what everyone was thinking, feeling empowered to continue with this research and hopefully contribute to prevention of this in our water system.”

The scientists on board weren’t there simply to document the Bay’s many ailments, however. They had joined the 10-day cruise to pave the way for a much larger goal: a geostationary satellite that could provide constant, detailed coverage of coastal health.

Click to continue »

Posted in Ecology, Interns, Publications, Solar Radiation, Water Quality | Comments Off on The Satellite That Could Save the Coasts