Posted by Kristen Goodhue on December 19th, 2014

by Heather Soulen, research technician

When I mention that we use “glue sticks” at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center to help answer research questions about wetland ecology, I get looks of confusion and amusement. People often think I am using:

|

or |

|

But, what I really mean is that I use these:

Click to continue »

Posted in Ecology, Fisheries, From the Field, SERC Sites and Scenes | Comments Off on Not Your Everyday Martha Stewart Glue Sticks

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on December 15th, 2014

by Michelle Marraffini, SERC marine biologist

SERC diver Lina Ceballos carries sampling equipment down to depth to survey species underwater.

(Michelle Marraffini/SERC)

The sun shimmers on the still waters of Monterey Bay, Calif., this beautiful October morning as we prepare for our dive survey. As we stand on the shore unloading our sampling gear, we can see the tops of giant kelp break the surface and an otter munching on a freshly caught crab. We’re about to dive into the Pacific Ocean in search of nonnative species on the outer coast.

Click to continue »

Posted in Ecology, From the Field, Invasive Species | Comments Off on From the Field: Diving Into the Kelp Forest

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on November 26th, 2014

by Kristen Minogue

Alewives, one of two species of River Herring in Chesapeake Bay. (Geoffrey Gilmour-Taylor)

It’s no secret that River Herring are in trouble. There was a time, back in the 1950s, when Maryland fishermen regularly pulled in 4 million pounds or more a year of the silver fish. Then something mysterious happened. Herring harvests generally fluctuate from year to year. But in the 1970s, they fell and never came back up. For the last four decades, commercial fishermen in Maryland have been lucky to catch a few hundred thousand a year. Now they catch none.

Click to continue »

Posted in Ecology, Fisheries, Interns | Comments Off on Saving the River Herring: Don’t Let the Good Die Young

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on November 18th, 2014

Bread, flour, cornmeal, rice and pasta. (Scott Bauer/USDA)

by Kristen Minogue

Food doesn’t typically get the spotlight in talks on climate change. Even when human health enters the picture, heat waves and category 5 hurricanes often dominate coverage. But as the Earth changes, so does agriculture. That raised just one of several questions scientists wrestled with at the Smithsonian’s second climate change symposium, titled “Living in the Anthropocene”: What will the world’s 7 billion people eat?

Click to continue »

Posted in Classes and Events, Climate Change, Ecology | Comments Off on Feeding the World in the Age of Humans

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on November 10th, 2014

by Kristen Minogue

Menhaden fish kill in Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island. (Chris Deacutis)

A full 94 percent of the world’s dead zones lie in regions expected to warm at least 2 degrees Celsius by the century’s end according to a new report from the

Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and the

Smithsonian Environmental Research Center published Nov. 10 in

Global Change Biology. The

paper states that warmer waters—mixed with other climate change factors—make for a dangerous cocktail that can expand dead zones.

Dead zones form in waters where oxygen plummets to levels too low for fish, crabs or other animals to survive. In deeper waters, dead zones may last for months, as with the annual summer dead zone in the Chesapeake Bay. Temporary dead zones may occur in shallow waters at night. The largest dead zones in the Gulf of Mexico and Baltic Sea can cover more than 20,000 square miles of the sea floor. The number of dead zones across the world is growing exponentially, doubling each decade since the 1960s.

“They’re having a big impact on life in the coastal zone worldwide,” said Keryn Gedan, a co-author and marine ecologist at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center and the University of Maryland. “A lot of people live on the coast, and they’re experiencing more fish kills and more harmful algal blooms. These are effects of dead zones that have an impact on our lives.”

Click to continue »

Posted in Publications | Comments Off on Dead Zones Likely to Expand as Coastal Waters Warm

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on October 9th, 2014

Charles McC. Mathias Laboratory (Smithsonian Environmental Research Center)

by Kristen Minogue

On September 19, the doors officially opened inside what’s targeted to be the Smithsonian’s first LEED-Platinum building: the Charles McC. Mathias Laboratory at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center.

The vision for a more sustainable lab emerged in the 1990s. Six years ago, SERC director Tuck Hines shared the idea with the then-new Secretary of the Smithsonian, Wayne Clough, on his first visit to the SERC campus.

“Tuck’s enthusiasm was infectious, and I told him then and there, you have my full support. We have to get this done,” Clough said. “But back then, it was just a dream….Today, six years from that first discussion, we’re here today to say, the dream has been fulfilled.”

Click to continue »

Posted in Classes and Events, SERC Sites and Scenes | Comments Off on Mathias Lab Opens New Era of Sustainability

at Smithsonian

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on September 30th, 2014

Jellyfish Chrysaora quinquecirrha (Lori Davias)

by Kristen Minogue

Every summer, the food web in Chesapeake Bay gets jostled around as two plankton-eating predators jockey for power: comb jellies and jellyfish. Most smaller species don’t have a stake in the battle—both predators eat zooplankton and fish eggs, after all. But for young oyster larvae, the victor could make the difference between being protected civilians or collateral damage.

Click to continue »

Posted in Ecology, Fisheries, Publications, Water Quality | Comments Off on Oysters and the Chesapeake’s Jellyfish Wars

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on August 29th, 2014

by Kristen Minogue

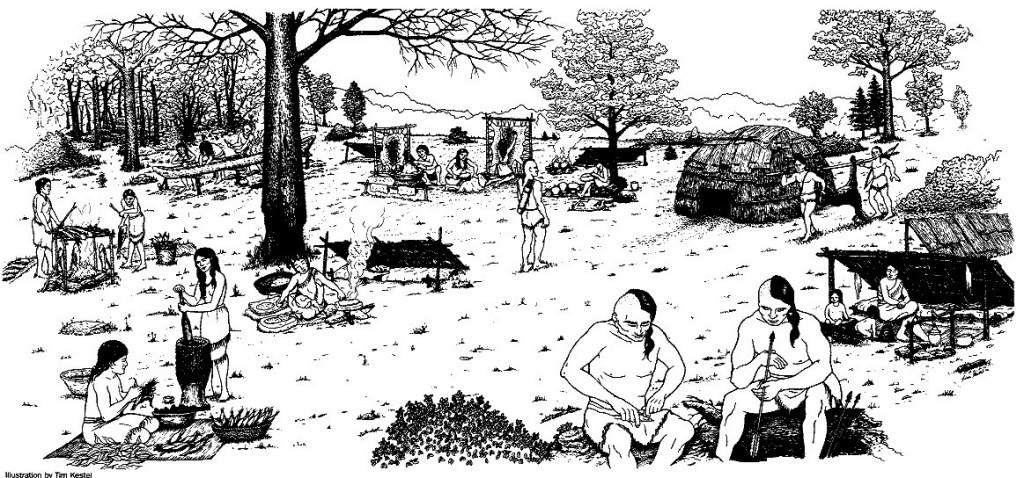

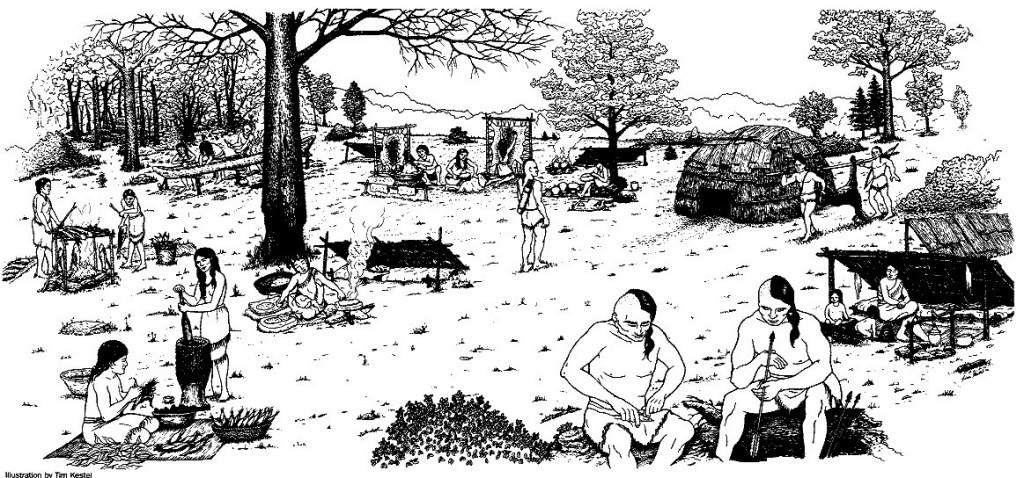

Piscataway Indians lived on the Rhode River up to colonial times, though anthropologists believe they used the land for temporary campsites, not permanent settlements.

For more than 10,000 years, Native Americans hunted and fished in the Chesapeake. Broken pottery, village sites, burial grounds and other artifacts bear witness to their near-continuous presence around the Bay. But one type of artifact—ancient trash piles called shell middens—hasn’t received as much attention. And these tell another important story.

Click to continue »

Posted in Archaeology, Climate Change, Land Use, Publications, SERC Sites and Scenes | Comments Off on Why 900 Years of Ancient Oysters Went Missing

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on August 21st, 2014

By Sarah Hansen

Tony Thomas (left), education program coordinator at the Anacostia Community Museum, supervises while students Donovan Eason (center) and DaWayne Walker run a chemical test on a water sample.

“Is the net like a Spongebob jellyfish net?” student Cristal Sandoval asked. Alison Cawood, citizen science coordinator at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC), used another analogy to explain: “It’s like a bowl with holes in it for pasta.” Light bulbs came on around the room and a knowing, “Oh,” escaped the lips of at least a dozen students.

Click to continue »

Posted in Ecology, Programs, SERC Sites and Scenes, Water Quality | 2 Responses »

Tags: citizen science

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on August 21st, 2014

by Melissa Pastore, biology graduate student at Villanova University

Melissa Pastore in a marsh near Delaware Bay.

(Lori Sutter)

What if we could create a giant sponge capable of soaking up nitrogen pollution? It turns out that the Chesapeake Bay, which has experienced a rapid increase in nitrogen pollution from municipal and agricultural sources over the last few decades, already contains a natural version of this sponge: marshes fringing the Bay. But global change—and the nitrogen pollution itself—could change how this natural sponge operates.

Click to continue »

Posted in Climate Change, Ecology, From the Field, Land Use, SERC Sites and Scenes, Water Quality | Comments Off on Marshes: Pollution Sponges of the Future