Posted by Kristen Goodhue on July 31st, 2015

by Chris Patrick

Rob Aguilar operates on a cownose ray. (SERC)

It’s 2 a.m. Rob Aguilar, biologist in the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center’s (SERC) Fish and Invertebrate Ecology Lab, meets a group of fishermen at a pound net in the Patuxent River. The net starts at the shore and juts far into the river. Fish traveling along the shore collide with the net and follow its length into a heart-shaped net at the end—the pound.

Today, the pound contains cownose rays. Not ideal for fishermen, but exactly what Aguilar wants. Last summer SERC researchers and collaborators surgically implanted acoustic tags in 31 rays to track their migration. This summer, they’re tagging 20 to 25 more rays from Maryland rivers.

Though native to the East and Gulf Coasts, much about cownose rays remains mysterious. Many fishermen and oyster growers consider rays a nuisance because they eat shellfish and travel in schools in the hundreds.

“The main conflict seems to be between guys who fish for oysters—especially aquaculture oysters because there’s a lot of money in that—and these rays they perceive as potentially eating up their profits,” says Matthew Ogburn, ecologist in the Fish and Invertebrate Ecology Lab. Click to continue »

Posted in Publications | 4 Responses »

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on July 27th, 2015

Eric Hazelton in a Phragmites patch on the Nanjemoy River in Maryland. (Rebekah Downard of Utah State University)

by Chris Patrick

On crime scene investigation shows, DNA forensic scientists sit in a darkened room, wearing lab coats and clutching clear vials over dramatic music. In a matter of hours, they conjure perpetrators to the scene of a crime or prove relations between separated kin simply from remnants of genetic material.

Researchers in the Plant Ecology and Molecular Ecology Labs at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) published a paper in July in Wetlands that has more in common with a CSI episode than you’d expect—though in their case, the process took months instead of hours.

There’s a strain of Phragmites australis, the common reed, that’s native to North America. But the population of an invasive strain from Europe, introduced in the 1800s, suddenly boomed without warning in wetlands around the Chesapeake Bay in the 1980s. SERC scientists had some ideas about what might have caused the sudden explosion, so the team attempted to recreate the history of this sudden, aggressive invasion to test their theories. Click to continue »

Posted in Publications | 2 Responses »

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on July 24th, 2015

by Chris Patrick

Red Lionfish. (Jacek Madejski)

The lionfish (Pterois volitans) resembles a psychedelic fish-shaped peppermint, striped in red and white and decked with feathery, fan-like fins. But its venomous spines and invasive-species status make it much less innocuous than candy.

Lionfish are native to the Indo-Pacific. They’re popular aquarium fish—it’s likely ex-aquarium-owners introduced them into the Atlantic. They spread rapidly along the southeastern coast of the United States, into the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean.

Lionfish flourish in their introduced range, where they have no predators. They breed quickly—a female can produce up to two million eggs per year. They live a long time, sometimes more than 15 years. And they’ll eat basically anything that fits into their mouths, decimating populations of native marine animals with their voracious, indiscriminate appetites. When they arrive at a reef, they can reduce the number of native fish by 80 percent.

But lionfish may also be harmful to the native fish they can’t eat. A recently published PLOS ONE study reports that invasive lionfish are parasitized less than native fish. Click to continue »

Posted in Publications | Comments Off on Yet Another Reason Lionfish Make Such Good Invaders

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on July 20th, 2015

by Kristen Minogue

How exactly does one prepare for a 100-day voyage to the Arctic?

Matt Rutherford on a pollution survey across the Pacific (courtesy Nicole Trenholm)

“Chaotically,” says Matt Rutherford, head of the nonprofit Ocean Research Project. He’s sitting in the cabin of the Ault, a 42-foot-long sailboat in Annapolis that will embark the next day on a research cruise to Greenland. Rutherford and his partner, Nicole Trenholm, will navigate unexplored fjords collecting data for the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) and NASA. The 8,000-mile round-trip journey will take them to some of the few uncharted spots left on the map. But first they have to finish packing.

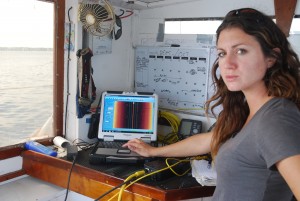

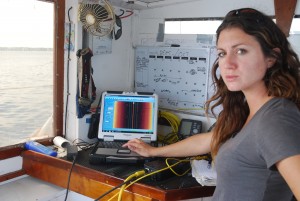

Nicole Trenholm tracks data on a Rappahannock River survey (courtesy Matt Rutherford)

“You’re always paying attention to how much water you have, how much power you have, how much fuel you have,” says Trenholm, a marine scientist who joined Rutherford in 2013. “It’s kind of a game.”

To conserve water, they’re running the sinks and showers with saltwater. The cabinets in the Ault’s galley are stuffed with trail mix, spices, Swiss Miss cocoa and freeze-dried food.

Click to continue »

Posted in Climate Change, Ecology | Comments Off on Cruising the Arctic’s Forgotten Fjords

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on July 16th, 2015

by Chris Patrick

Lovers of both the Smithsonian and the selfie stick, rejoice! Though the infamous monopods are banned in Smithsonian museums and galleries, they’ve found a new arena of use: labs.

Well, in one lab at least. Researchers in the marine ecology lab at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) are using selfie sticks to record fish behavior without scaring them. SERC’s marine ecology team wants to see if fish raised in low-oxygen conditions acclimate to breathing less oxygen. “I have never heard of someone else using the selfie stick for science,” said Seth Miller, a postdoctoral fellow in the marine ecology lab and collaborator on the project. “Although it probably occurs. Ecologists are pretty resourceful.”

Ashley Collier records a fish without scaring it by using a selfie stick. (Chris Patrick)

Click to continue »

Posted in Publications | Comments Off on Fish Don’t Fear Selfie Sticks

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on July 13th, 2015

Interns Julianne Rolf and Emily Bulger. (Chris Patrick)

by Chris Patrick

When 11 Smithsonian Environmental Research Center interns piled into a van headed for the Oyster Olympics, they had no idea what was in store. For the next three hours, they shoveled, scooped, scraped, sweated, poured, piled, folded, clamped, ran, and acquired minor injuries competing against interns from other environmental organizations in the area. Though the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF) holds the Oyster Olympics annually at its Discovery Village in Shady Side, Md., this was the first year SERC interns vied for the golden oysters (think of gold-painted shells hanging from rope). From the get-go, it was clear SERC interns were the underdogs. Click to continue »

Posted in Publications | Comments Off on Interns Compete in Oyster Olympics

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on July 8th, 2015

Male and female bluebirds at a nest box. (Matt Storms)

by Chris Patrick

Eastern bluebirds resemble flying, fist-sized jewels. Males are sapphire colored—royal-blue heads, backs, and wings contrast with rust-colored chests. Females are more gray than blue, but their wings are subtly tinted the same sapphire hue.

Since 2008, citizen scientists have monitored bluebirds at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC). The Bluebird Project is citizen science intern Caroline Kanaskie’s self-proclaimed “baby” this summer. She is uncovering why bluebird numbers at SERC have been lower than usual. Click to continue »

Posted in Archaeology, Classes and Events, Ecology, Extreme Weather, From the Field, Interns, SERC Sites and Scenes | 1 Response »

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on July 2nd, 2015

by Chris Patrick

7-year-old Vivian and 6-year-old Gordon kneel in the dirt looking for insects.

“Camp Discovery!” shouts Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) education intern Josie Whelan.

“SCIENCE NINJAS!” a dozen 6- to 8-year-old campers respond as they strike ninja-esque poses. This is a callback, used by the three education interns—Henry Lawson, Addie Schlussel, and Whelan—to grab the attention of talkative future first- and second-graders at Camp Discovery. The education interns designed Camp Discovery this year, organizing a week of visits to SERC’s forests, fields, docks, and wetlands to foster understanding and respect for nature in campers. Click to continue »

Posted in Classes and Events, Ecology, Education, Interns, SERC Sites and Scenes | Comments Off on “Science Ninjas” Capture Bugs at Camp Discovery

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on June 26th, 2015

by Chris Patrick

Laurel Martinez checks her bread crate naked goby nests.

Plastic bread crates rest on the floor of the Rhode River, suspended by ropes from the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center’s dock. Eight PVC pipes arranged in a starburst sit horizontally on the bottom of the bread crates. In each tube there is a rolled sheet of thin, clear plastic. These rolled sheets are goby egg nests.

Or they’re supposed to be. Laurel Martinez, intern in the marine ecology lab this summer, slides out a plastic sheet and exclaims, “The mud crabs took over!”

This isn’t the plan. She wants the sheets to house naked gobies, bottom-dwelling fish. Martinez needs naked goby eggs for her summer project. Female gobies, who usually lay their eggs inside dead oyster shells, are supposed to go into the tubes, lay eggs on the plastic sheet, and leave. A male will fertilize the eggs and stay with them, guarding and caring for them until they hatch. Click to continue »

Posted in Climate Change, Ecology, From the Field, Interns, SERC Sites and Scenes | Comments Off on Building Plastic Nests and Gutting Fish in the Room of DOOM

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on June 23rd, 2015

by Chris Patrick

Tepolt holding a Humboldt squid at Hopkins Marine Station in Pacific Grove, California. (Tom Hata)

Before I was the science writing intern at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC), I volunteered in SERC’s marine invasions lab sorting white-fingered mud crabs with Monaca Noble, researcher and public relations coordinator. The mud crabs are tiny, ranging from the size of a tick to the size of a quarter. They reek of preservative alcohol, and milky mittens glove their pincers. While sorting, I met Carolyn Tepolt, a postdoctoral fellow at SERC.

34-year-old Tepolt (which sounds like a fusion of “teapot” and “catapult”) offered me homemade lemon bars the day we met. Working together, we discovered we were both undergraduates at the College of William and Mary—we lived on the same floor of the same freshman hall 14 years apart. Tepolt visited the lab to learn the crab-sorting process because this summer she will use genetics to study how mud crabs are adapting to their parasite, Loxothylacus panopaei, or Loxo. Click to continue »

Posted in Ecology, Invasive Species, Parasite Hunting | Comments Off on Under the Apron, into the Genome