Posted by Kristen Goodhue on July 12th, 2017

How California’s Record-Setting Rains Are Reshaping the Ecology of San Francisco Bay

By Ryan Greene, science writing intern

The San Francisco skyline as seen from San Francisco Bay. Credit: Ryan Greene/SERC

The Smithsonian Environmental Research Center’s (SERC) largest West Coast outpost sits on San Francisco Bay in Tiburon, California. The Tiburon branch, affectionately known as SERC-West, serves as the nexus of SERC’s research activities on the western coast of North America. At a whopping 2,462 miles from SERC’s main campus on the Chesapeake Bay in Maryland, SERC-West can feel a bit remote. In an attempt to bridge this distance, we’re launching “Tidings From the Sunset Coast,” a summer story series about all things SERC-West. The first snippet is a story about the wildly wet winter California experienced this year and what all this fresh water means for the marine life in San Francisco Bay. Enjoy!

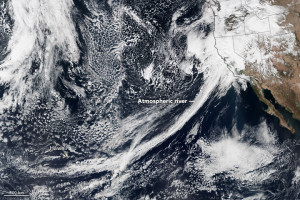

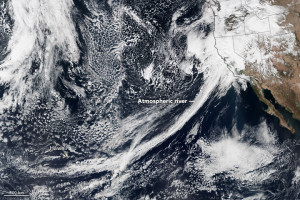

Image from NASA’s VIIRS satellite show one of many “atmospheric rivers” which slammed the California coast this past winter. Credit: Jesse Allen and Joshua Stevens/NASA Earth Observatory

When it comes to rain in California, the last few years have been a feast-or-famine affair. After a bitter drought that sported some of the driest years on record, this past winter brought more precipitation than the northern parts of the state have ever documented. To put it lightly, the weather has been extreme. And while the wet winter has refilled reservoirs and beefed up the snowpack, leading Governor Jerry Brown to end the drought state of emergency in all but four counties, it has also wreaked its fair share of havoc.

Here at SERC-West, scientists have been following another part of this story: the bombardment of freshwater runoff that inundated San Francisco Bay this winter. All the fresh water from the rain drastically reduced the saltiness (a.k.a. salinity) of the Bay. For many plants and animals used to saltier water, this was simply too much to handle. The devastation has been widespread, and according to ecologist Andy Chang, who currently heads up SERC-West, in some areas, the changes to the ecosystem might be less than fleeting.

“We’re kind of expecting to see local extinctions of some species that were here before,” he says. Click to continue »

Posted in California, Ecology, Invasive Species, SERC Sites and Scenes, Tidings from the Sunset Coast, Water Quality | 1 Response »

Tags: california, ecology, fouling communities, oysters, San Francisco Bay, serc-west, wet winter

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on July 10th, 2017

by Joe Dawson, science writing intern

Looking at the Kirkpatrick Marsh on the Rhode River, a time machine is not the first thing that comes to mind. Tall grasses dominate the landscape, with vertical PVC pipes popping up here and there and octagon-shaped chambers rising out of the wetland every ten paces or so. Take a step off the walkway, and you might lose a shoe. But five experiments on the marsh are designed to take sections of the marsh into the 22nd Century, and the marsh has been dubbed the Global Change Research Wetland, or GCReW. The expertise that GCReW scientists have in simulating the future brought National Museum of Natural History scientists here to mirror the past.

Rich Barclay and Scott Wing are paleobotanists at the National Museum of Natural History. Paleobotanists are the ones who stare at leaves in Jurassic Park and say, “Alan, these plants haven’t been seen since the Cretaceous Period,” as everyone else stares at brachiosauruses. Ancient plants are their bread and butter, and for Wing and Barclay, the bread is toasted and the butter melty. They study one of the warmest periods in the last 100 million years, the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM). During this period, global temperatures skyrocketed, increasing by 10-15 degrees Fahrenheit. By looking at plants that grew during this time, they hope to learn more about what Earth was like 55 million years ago.

Large growth chambers being built around newly-planted ginkgo trees on the SERC campus (Credit: Rich Barclay)

Barclay, Wing, and colleagues have started another experiment on the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center’s (SERC) campus, in a forest a few miles down the road from the GCREW marsh. The project grows ginkgo trees in varying carbon dioxide levels. They hope to study these trees and compare them to fossil specimens to learn about the past. Click to continue »

Posted in Climate Change, Ecology, Publications, SERC Sites and Scenes | Comments Off on Time Travel, with Trees

Tags: carbon dioxide, citizen science, collaboration, ecology, ginkgo, national museum of natural history

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on July 5th, 2017

by Joe Dawson, science writing intern

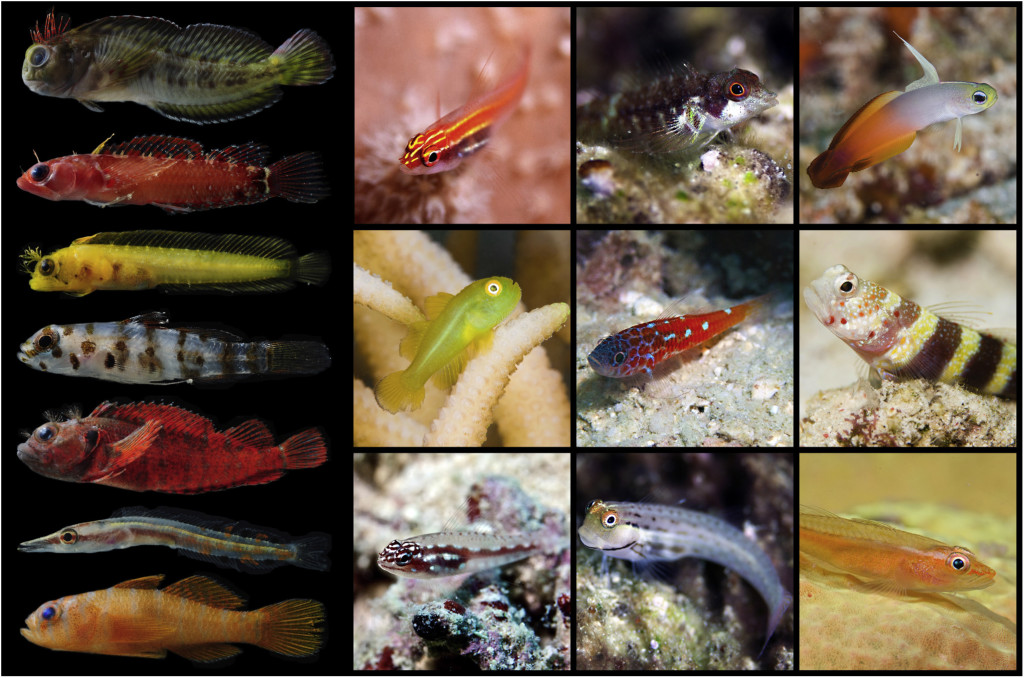

Go snorkeling on a coral reef, and you’ll have a hard time not being impressed by the abundance and variety of the fish there. But the fish most divers see make up less than half of the number (and less than half the species) of fish on the reef. Cryptobenthic reef fishes comprise the other half. These fish are small, usually less than 2 inches in length, and hide in coral habitats, either by appearance or by their behavior. Even scientists have been slow to start searching for them, but cryptobenthics are turning up in about every reef habitat where scientists have bothered to look! In the June 5 issue of Current Biology, SERC Scientist Simon Brandl and colleague Christopher Goatley of the University of New England published a quick guide to cryptobenthic reef fishes. Brandl thinks that these little fishes deserve more recognition, and we agree! Therefore, we’re happy to present these honorees with the following awards.

Coolest Camo

Runners Up: Frogfishes (Family Antennariidae), Scorpionfishes (Family Scorpaenidae)

The painted frogfish, Antennarius pictus (Credit: John E. Randall/Hawaii Biological Survey, used under CC BY-NC 3.0)

Weird and tricky, frogfishes have plump, short bodies. They’re often covered in spines or even hair-like appendages and prefer to stay still, waiting and blending in, for prey to swim close enough that they can gulp them. The deep-sea dwelling anglerfish is one famous member of this group.

Scorpionfish are also sit-and-wait predators, using their feathery scales or skin flaps to look like rocks or coral, then pouncing on nearby prey. The most renowned member of this group is the lionfish. Click to continue »

Posted in Ecology, Publications | Comments Off on The Tiny Fish Awards!

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on June 26th, 2017

by Joe Dawson, science writing intern

Ian Davidson in Cork, Ireland (Credit: Ian Davidson)

Ian Davidson is continuing his work at SERC in a new role: as principal investigator of his own lab. From diving under massive cargo ships to studying an invasive organism ugly enough to be nicknamed ‘rock vomit,’ Ian Davidson looks at how human activities affect marine ecosystems. This includes the methods by which humans transfer marine life around the world (mainly shipping), the effects of coastal development on nearshore environments, and management and policy with regard to marine invasions and organisms.

This is the third of three profiles about the young scientists leading SERC’s newest labs. Edited for clarity and space.

How did you get interested in your area of study?

I grew up in Cobh (pronounced, “Cove”), a small harbor town on the south coast of Ireland, so I had plenty of time in rock pools when I was young. My mother grew up a stone’s throw from the shoreline, right in front of the main shipping channel there, so we were always keeping an eye on the to-and-fro of the port. My dad worked in a shipyard until it closed down too, so I suppose the ingredients were there to pursue a career that heavily featured marine biology and shipping! Click to continue »

Posted in Alaska, Ecology, Interviews, Invasive Species | Comments Off on Q&A: Ian Davidson, Aquatic Inquirer

Tags: ecology, invasive species, marine invasions

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on June 23rd, 2017

by Kristen Minogue

Katrina Lohan in New Zealand’s Abel Tasman National Park. (Credit: Chris Lohan)

Weird truth: There are more parasites on Earth than non-parasites. Katrina Lohan would know, having spent over a decade studying them. After five years with the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center’s Marine Invasions Lab, Lohan is now in charge of launching the center’s new Marine Disease Ecology Lab. In this Q&A, meet some of the weirdest parasites she’s encountered and learn how DNA is helping her unlock their secrets.

This is the second of three profiles about the young scientists heading SERC’s newest labs. Edited for brevity and clarity.

What do you find most fascinating about parasites?

I really like it when stories are complicated. And adding parasites certainly complicates any story. But I’m also intrigued by the David and Goliath aspect of it, that parasites are super small, [often] overlooked, and most people don’t even think about them in terms of what role they play in ecosystems or what they could possibly be doing. Most people would sort of shrug off—oh, they’re probably not really that important. And yet, they’re extremely important. The more we learn about parasites, the more we realize that they control their hosts. They can actually completely change the behavior of their hosts. Click to continue »

Posted in Ecology, Interviews, Invasive Species, Parasite Hunting | Comments Off on Q&A: Katrina Lohan, Marine Parasite Hunter

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on June 21st, 2017

New study shows hardened shorelines may mean fewer fish and crustaceans.

by Ryan Greene

A new SERC study shows that both bulkheads (left) and riprap revetment (right) are associated with lower abundance of several species of fish and crustaceans in the Chesapeake Bay and the Delaware Coastal Bays. Credit: SERC

For decades, ecologists have suspected that hardened shorelines may impact the abundance fish, crabs, and other aquatic life. But now they have evidence that local effects of shoreline hardening add up to affect entire ecosystems. A new study by scientists at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) shows that more shoreline hardening means fewer fish and crustaceans in our waters.

Given the predictions for the coming years (i.e. rising seas and more of us living on the coast), this finding is a cause for concern. Many people will likely try to protect their land from flooding and erosion by armoring their shorelines with vertical retaining walls (bulkheads) or large rocks (riprap revetment). But as SERC researchers found in their new paper, published in Estuaries and Coasts, the impact of these hardened shorelines adds up.

Lead author and former SERC postdoc Matt Kornis likens shoreline hardening to littering. While each individual bit of trash isn’t a huge problem, the combined effect can be enormous. Kornis, now a biologist for the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, says the same is true of shoreline hardening. Each individual bulkhead or riprap revetment may not be catastrophic, but cumulatively they can contribute to shrunken populations of ecologically—and economically—important species like the blue crab.

“Shoreline hardening can cause loss of habitats important for young fish, like wetlands and submerged vegetation,” Kornis says. “That may be one reason we observed low abundance of many species in estuaries with a high proportion of hardened shoreline.” Click to continue »

Posted in Climate Change, Ecology, Fisheries, Land Use, Publications | 2 Responses »

Tags: Chesapeake Bay, ecology, living shorelines, sea-level rise, shoreline hardening

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on June 20th, 2017

That’s why Uzay Sezen carries a crossbow and liquid nitrogen into the forest with him.

by Ryan Greene

Intern Alex Koure (left) and postdoctoral researcher Uzay Sezen (right) are using a crossbow to get leaf samples from hard-to-reach branches. A fishing line attached to the arrows helps them shake down leaves from the canopy. Credit: Ryan Greene/SERC

Uzay Sezen is a new postdoc at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC), and he’s on the hunt for good data. Literally.

Uzay Sezen with his crossbow and liquid nitrogen in Harvard Forest. Credit: SERC

With senior scientist Sean McMahon and other members of the Quantitative Ecology Lab, Sezen is embarking on a multiyear study which aims to unveil the genetic patterns of tree growth. Their mission: Find out if tree species present at both SERC and Harvard Forest grow in the same way, and whether there are particular genes they express when they grow. Not only will this help us understand how trees respond to day-to-day changes in sunshine, temperature, and rainfall, but it may provide insight into how forests will react (and already are reacting) to global factors like climate change.

Since about 2009, scientists at SERC have been using metal bands called dendrometers to measure how trees grow (within a hundredth of millimeter!) over years, seasons, weeks, and even days. According to SERC technician Jessica Shue, combining these physical measurements with Sezen’s genetic analysis may help reveal what makes some trees in the forest winners and others losers.

“Now that we can look at the genetics, we can look at a much finer scale at what’s causing some trees to be dominant in the canopy, and others of the same species [to be] stuck in the understory,” she says.

How, though, do you ask a tree which genes it’s using?

Click to continue »

Posted in Climate Change, Ecology | Comments Off on Humans Are Short and Trees Can’t Talk

Tags: Crossbow ecology, Forest ecology, Leaf hunting, Quantitative Ecology, RNA sequencing, Uzay Sezen

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on June 19th, 2017

By Joe Dawson

A stand of mangrove trees in Florida (Credit: Yinan Chen under CC0/Public Domain license)

With their tall, arching roots reaching down like hands into the water, mangrove trees can look downright creepy. And yet they’re critical species for the environment—and humans—on five different continents: They can create their own islands, provide one-of-a-kind habitats for wetland creatures, and store carbon like mad. They also protect shorelines from storms and tsunamis. Unfortunately, and perhaps unsurprisingly, humans are destroying them at a rate that may doom them within a century.

Aquaculture, urban development, tourism, and agriculture are threatening mangrove habitats around the world. Like many natural ecosystems, they are being cut down and destroyed to make way for human endeavors, and human pollution is taking its toll on their growth at the same time. But even as their total acreage decreases, they’re gaining ground in some places. Climate change is causing mangroves to move beyond their tropical habitats and take over neighboring salt marshes, but not always predictably. In North America and South Africa, they are moving toward the poles, while in Australia they are expanding along an east-west axis. All these disappearances and migrations present a riddle for scientists—but one they will need to solve to prevent habitat loss and prepare for a warmer future. Click to continue »

Posted in Publications | Comments Off on Predicting the Future of Migrating Mangroves

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on June 16th, 2017

by Kristen Minogue

Kim Komatsu in Konza Prairie, Kansas, home to one of the first Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) programs. (Credit: Arjun Potter)

Kim Komatsu does big-picture ecology. The newest senior scientist at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, Komatsu is leading the center’s Ecosystem Conservation Lab. But while working on large-scale global experiments, she also delves into the microscopic world of bacteria. In this Q&A, discover how bacteria give certain plants an edge, and how she blends the very large and the very small.

This is the first of three profiles about the young scientists heading SERC’s newest labs. Edited for brevity and clarity.

You’ve done a great deal of work with legumes—plants in the bean and pea family. Can you talk about their weird relationship with rhizobial bacteria?

The [legume] plants and bacteria are in a mutualism where the plants fix carbon into sugar and give it to the bacteria, and the bacteria are able to take nitrogen from the atmosphere and give it to the plants. This is a source of nitrogen that no other plants have access to. Most plants have to take [nitrogen] up from the soil. Because of this mutualism, legumes can get nitrogen from another source, and that often makes them very successful in different, especially harsh environments….

It’s interesting to think about the different legume species, and how good they are at enforcing cooperation from the bacteria. Thinking about the bacteria as not only potentially being beneficial, but [also possibly] cheating the system—trying to take carbon from the plants and not give back as much nitrogen, especially under high soil nitrogen conditions. Click to continue »

Posted in Climate Change, Ecology, Interviews | Comments Off on Q&A: Kim Komatsu, Ecosystem Conservation Ecologist

Posted by Kristen Goodhue on June 15th, 2017

Fishing, camping, and walking the dog can all have unintended consequences. (Credit: pixabay.com, 1,2,3. Used under Creative Commons CC0 license)

By Joe Dawson

Nothing seems to draw people outside like a beautiful summer weekend. A rain-free Saturday could mean taking the boat out on the water for some fishing or a family camping trip. Conservationists have found, however, that many summer activities carry the risk of spreading invasive species. A species gets the name “invasive” if it is not native to a location and causes environmental and economic damage. Here are five popular activities that can spread invaders–and tips for enjoying them safely: Click to continue »

Posted in Ecology, Invasive Species | Comments Off on Five Summer Activities That Can Spread Invasive Species