by Chris Patrick

Legend says it all started with a single orchid bloom. This bloom, an accident, sparked a phenomenon so pervasive in Victorian England that its name, orchid delirium, was shortened to orchidelirium, a d excised to indicate the oneness of orchids and madness.

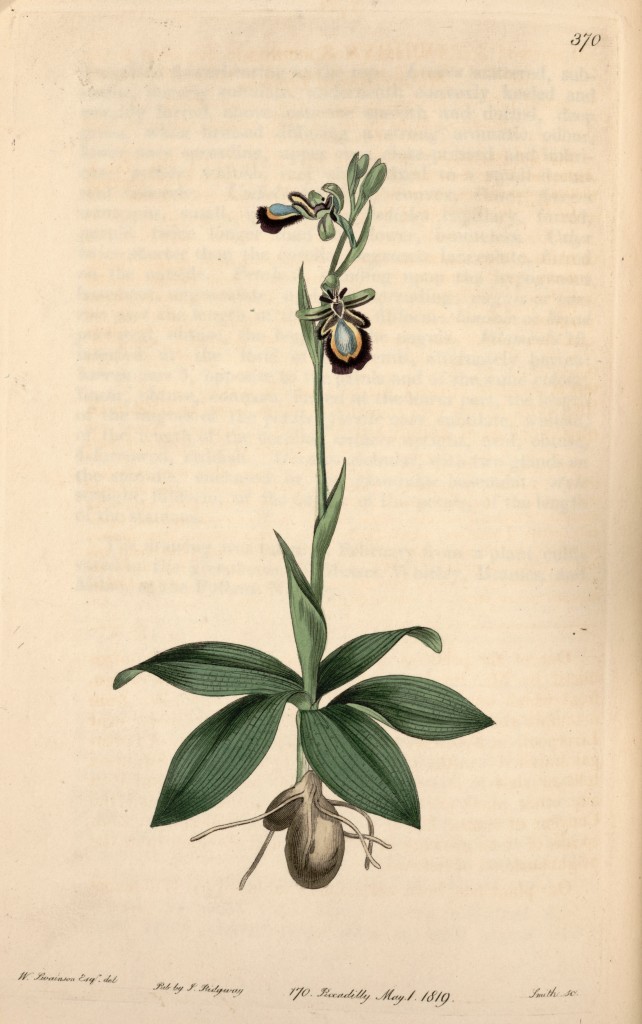

The story begins like this: In 1818, a man named William Swainson sent plants from Brazil to London, using what he believed to be parasitic plants as packing material. When the package arrived, one of the plants was in bloom. Its vivid hue and strange shape were unlike anything most European eyes had ever beheld in the way of flowers. Europe fell in love. And so began orchidelirium, the European obsession with orchids.

In truth, Swainson, an English biologist, probably knew that the “parasitic plants” were indeed orchids and recognized their real value when shipping them to Europe. Europeans had cultivated them on a small scale since the 1700s, though their popularity then was nonexistent compared to the widespread orchid fanaticism of the 1800s.

What about orchids is so compelling? Beautiful, exotic, diverse, cunning—orchids seduce. Some believe the orchid allure lies in the flowers’ bilateral symmetry, which mimics that of the human face. These plants make people want them, no matter the cost.

In the 19th century, the average Englishperson could not afford to collect orchids, however desirable they were. Collection was a privilege of the rich. Wealthy orchid collectors employed hunters to travel the world, especially the tropics, in search of rare species.

To be an orchid hunter was to risk one’s life for flowers. There were many perils. Tales abound of hunters killed by disease, accident, animals, the elements, or murdered by other hunters in fierce competition for the flora. Instead of murdering their rivals, sometimes hunters would murder their rivals’ flowers…by urinating on them. Surviving hunters delivered their petal-ed treasures to collectors who filled greenhouse upon greenhouse.

On a Brazil-bound boat, Victorian-era hunter William Arnold began a tiff with another orchid hunter also hunting for Brazilian orchids. Enraged at the mere prospect of hunting for the same orchids, the two began to fight, flashing firearms and nearly dueling. Though they emerged unscathed, in other orchid-hunter fights, both sides didn’t always come out alive.

Orchidelirium still exists to some extent. Plenty of modern-day collectors still fill greenhouse upon greenhouse with orchids. The Convention of International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora banned the collection of wild orchids in 1973. But people poach. While habitat loss remains the biggest threats to endangered orchids, illegal orchid harvesting and smuggling may also contribute to their decline.

Perhaps the most well-known modern orchid fanatic is an American horticulturist named John Laroche. In 1993 he poached 136 orchids filling several garbage bags and pillowcases from the Fakahatchee Strand State Preserve in Florida with the help of Seminole tribe members, including the rare ghost orchid. He claimed he only did it to clone and cultivate endangered species. Susan Orlean chronicles his crime, trial, and life, in her nonfiction book The Orchid Thief.

Another modern collector, Englishman Tom Hart Dyke, risked his life for orchids in the tradition of the Victorian hunters. While hunting in the Colombian jungle with a friend in 2000, a guerilla group captured him and his companion and held them prisoner for nine months. When they were released, they had no orchids to bring home.

This is the orchid allure. Throughout history, people have been caught illegally harvesting orchids, stealing orchids from other collectors, killing for orchids. Orchids make people crazy. Even when it doesn’t involve being kidnapped or breaking the law, the orchid obsession is intense. Collectors have been known to name orchid heirs in their wills, because their plants will outlive them. And there is orchid everything: conventions, forums, websites, books, babysitters, doctors, boarding houses.

Next time you’re at the grocery store and see an orchid for sale next to the potatoes, remember orchidelirium. Think of those who have died over its cousins, and ponder why this family stirs such fervor.

If you’re also a victim of orchidelirium, join the fight to help protect the 200-plus orchids that blossom in North America. Check out the North American Orchid Conservation Center (NAOCC), a collaboration between the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, the United States Botanic Garden and organizations across the continent to preserve its native orchid species. You can feed your orchidelirium even further by exploring hundreds of species on Go Orchids, and searching for the ones nearest you.

(William Swainson’s orchid illustration and portrait are in the public domain due to creation before January 1, 1923.)