by Heather Soulen, research technician

When I mention that we use “glue sticks” at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center to help answer research questions about wetland ecology, I get looks of confusion and amusement. People often think I am using:

|

or |  |

But, what I really mean is that I use these:

|

+ |  |

+ |  |

We Don’t Live in a Linear World

You’re probably wondering how these three items are used in ecological studies. Usually, it starts out with big-picture-type questions, like, “Are the interactions between predators and prey different in native and invasive tidal marshes?” Funny thing about big-picture questions: They’re often too difficult to be answered in a direct, linear way, because the natural world is ever-changing, highly complex and interconnected. As a result, we must reimagine big-picture questions, and break them down into a series of smaller, solvable questions that we later frame together to better understand the big-picture question. Therefore, one of the smaller questions might be, “At high tide, how much water is above the surface of both marshes (native and invasive) for small fish and invertebrates to use as refuge?” We know from other studies that small fish and invertebrates use tidally flooded marshes for many reasons, including to hide from predators. So, when the tide is high and has risen above the marsh surface, prey are able to hide from a predator amongst the marsh plants and limit the opportunities for predator-prey interactions.

Creativity in Science…“It’s a Good Thing”

The next logical step would be to measure how high and how far back the water gets at high tide. Now, it was at this precise moment that some of us on the project spiraled into slack-jawed expressions and head scratching, because how exactly do you measure this in some sort of quantifiable way that is easy, cost-effective and meaningful? I won’t go into the silly, eye-rolling ideas we came up with that clearly violated the “easy,” “cost-effective” and “meaningful” rules, but what I will amuse you with is the idea that the process of figuring this out is a creative one. In fact, the whole process of how science is done is creative and imaginative! We have to imagine all the possibilities as to if, why and how something occurs. We then have to be able to envision how each one of those possibilities might play out in order to narrow them down to a few promising and testable hypotheses.

Sometimes we might need to create a sampling device, a sampling system for an experiment, or simply something that holds a piece of research equipment. We often have to reimagine everyday items that we can easily and cheaply buy anywhere, only to turn them around and use them in unexpected ways to answer research questions. Everyday items like water-soluble glue, red food coloring and wooden dowels, for example. And then there’s MacGyvership! What is MacGyvership? It’s a problem-solving process typically performed on the fly, in less-than-optimal conditions, and without the appropriate or correct resources available. Even how you cultivate your research story, the “What does it all mean?” and “Why should anyone care about this?” requires creativity and imagination.

That Einstein Was a Hip Cat

You have to be a curious person to ask the big “what if,” “why,” and “how” questions. Creativity and imagination only fan the flames of curiosity. Einstein once stated in a 1929 interview, “I’m enough of an artist to draw freely on my imagination, which I think is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.” Yet, we must remember that imagination and creativity are also the vehicles by which we gain knowledge. They fuel our curiosity to ask the big-picture questions, and help us devise inventive ways to answer them, so that we might understand a little more about the natural world around us.

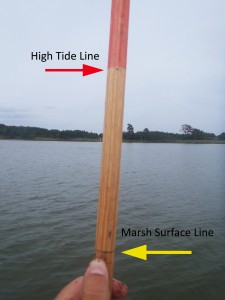

In the picture to the right, you can see where the tide has washed away the red food coloring and glue mixture from the dowel, returning the dowel to a natural, wood color. The line where the red and natural color meet (red arrow) indicates how high the tide was on that particular day. Now, let’s revisit our smaller, solvable research question: “At high tide, how much water is above the surface of both marshes (native and invasive) for small fish and invertebrates to use as refuge?” The answer is the distance between that line where the red and natural wood color meet (red arrow) and the marsh surface (yellow arrow)!

All images by Heather Soulen.

Heather Soulen is a research technician at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC). Recent projects have found her hauling giant seine nets to sample fish and invertebrate populations, counting jellyfish polyps, tracking dissolved oxygen in the Rhode and West Rivers at dawn, documenting the flora of SERC, and writing limericks and animated video scripts about science and the life of a scientist. You can read more about the Marine Ecology Lab’s predator-prey study here!